The election, now at its fever pitch, has turned Bihar into a theatre of competing arithmetic.

Unemployment remains one of Bihar’s biggest political concerns. Lokniti-CSDS surveys show it was the top issue for 9.1 per cent of voters in 2015, rising to 21 per cent by 2020.

In nearly every district, an undercurrent of anger simmers against ruling party MLAs who, locals say, “vanished” after the last election

As dusk falls over Tajpur in Samastipur district, the marketplace close to the highway glows under a mix of fairy lights and flickering bulbs. The air smells of fried litti (baked dough balls) and election dust. During the first phase of the election here, people voted in large numbers. But the discussion about who should come to power lingers on, albeit with a bit of scepticism about the past.

“Nitishji (incumbent Chief Minister Nitish Kumar) gave ten thousand (rupees) to women,” said Ranjit Kumar, a 37-year-old peon in a government-run school in Tajpur, stirring his tea slowly. “In response, Tejashwi said, he’ll give thirty thousand (rupees). The BJP also talked about new youth schemes. People got dizzy keeping count. Nobody knew what was (really) new and what (was) just another announcement.”

He smiled wryly. “Every day, a new promise landed on our heads. We just wanted to know which one would actually change something on the ground. According to me, the time has come for a change in the regime.”

Many voters were left confused by the many promises made throughout the campaign, right up to the final day on November 4. Across Bihar, from the bazaars of Sheikhpura in Patna district to the sugarcane fields of Champaran, the sentiment was similar. Competing pledges from both alliances blurred the line between policy and bribery, leaving voters torn between gratitude and doubt.

“The talk everywhere was who will give more—not who will govern better,” said Sanjay Singh, a schoolteacher in Arrah. “It felt like an auction, not an election.”

Season of Announcements

The election, now at its fever pitch, has turned Bihar into a theatre of competing arithmetic. Nitish Kumar’s Janata Dal (United) rolled out its Rs 10,000 assistance plan for women, calling it a “direct boost to dignity”.

Within days, Rashtriya Janata Dal’s (RJD) Tejashwi Yadav announced a grant of Rs 30,000. Posters sprouted overnight. WhatsApp groups buzzed with debates. And yet, on the ground, few seemed convinced.

While incumbents and hopefuls make promises galore at election rallies, one issue remains relevant across the state, affecting every family, every village, and every voter: unemployment.

“Even for Rs 10,000, the government will ask for 10 documents and make you go 10 times to the block office,” said Sunil Yadav, 22, a jobless graduate in Sheikhpura. “It is time for change. Twenty years of Nitish Raj was okay. But a lot needs to be done. People need to give opportunities to the other alliance as well.”

This divide—between older women’s gratitude and younger women’s aspirations—could play a role in shaping Bihar’s electoral math in unexpected ways.

Asked if RJD rule would lead to “Jungle Raj”, as Nitish Kumar proclaims, Yadav said, “By that standard we are (already) living in jungle raj. All the data shows that crime has gone up. It is time people need to stop demonising Lalu Yadav’s rule. Yes, mistakes were made, but RJD knows better than to repeat the same mistakes. Today’s voter is quite aware.”

In Darbhanga’s Alinagar, where BJP candidate Maithili Thakur’s campaign added a fresh cultural flavour, the reactions were similar. “We are not calculators,” said Rohit Jha, a student at C. M. Science College.

“We want sincerity, not sums. I think instead of announcing more freebies, Nitish Kumar should have given a plan for how he will do things he didn’t do in the last 20 years.” Despite being a Brahmin, Jha supports Tejashwi Yadav’s promise of one job per family over the NDA.

The Mirage of Jobs and Industry

Unemployment remains one of Bihar’s biggest political concerns. Lokniti-CSDS surveys show it was the top issue for 9.1 per cent of voters in 2015, rising to 21 per cent by 2020, and is expected to dominate voter priorities again this election.

The Periodic Labour Force Survey shows Bihar’s youth unemployment (ages 15-29) fell from 30.9 per cent in 2018-19 to 9.9 per cent in 2023-24. Despite the improvement, nearly one in 10 young people in the state remain unemployed.

Every conversation about Bihar’s politics eventually circles back to a haunting question: Where are the jobs? At Patna junction, under the yellow glow of tube lights, dozens of young men waited for the night train to leave for industrial cities across the country. Each carried a small backpack and a quiet sense of resignation.

“I have an ITI diploma,” said Amit Ranjan, 25. “I work at a private factory in Noida. I came home to vote, but honestly I’m not sure why. They talk about Rs 10,000, Rs 30,000—but we just want a chance to earn.”

He pointed at the platform. “Half the train will be filled with people from Bihar. If there were factories here, who would leave?”

With more than seven per cent of its population migrating for jobs, palayan is one of the top poll planks in Bihar. Data shows poll-bound Bihar ranks second to Uttar Pradesh in out-migration for jobs and has the highest multidimensional poverty rate in the country.

The Forgotten Constituencies

But it’s not just the numbers that bother voters—it’s the faces behind them. In nearly every district, an undercurrent of anger simmers against ruling party MLAs who, locals say, “vanished” after the last election.

In Gaya city, Shagufta Khatoon, a 62-year-old former school clerk, who runs a grocery shop, didn’t mince words. “We see them only on TV or hoardings. For five years, not one visit, not one meeting. Now suddenly they come with folded hands and promises.”

In Lahariyasarai in Darbhanga, 35-year-old Babloo Paswan did the math out loud. “Rs 10,000 or Rs 30,000—that’s one or two months’ survival. Then what? There are no industries, no jobs. These promises are like band-aids on a bullet wound.”

Nitish’s Women Card

And yet, amid the chorus of scepticism, one segment of voters continues to express guarded faith—women.

In rural Patna, 38-year-old Rekha Devi spoke softly but with conviction. “Nitishji gave us respect,” she said, referring to the liquor-prohibition policy enacted in 2016. “Men may curse it, but for us, it brought peace. My husband stopped drinking. The fights at home reduced. My children study better now.”

Nearby, Asha Kumari, an anganwadi worker, nodded. “He gave cycles to girls, toilets, electricity and reservations in panchayats. We may not have everything, but we got dignity.”

Every conversation about Bihar’s politics eventually circles back to a haunting question: Where are the jobs?

This trust, analysts say, is Nitish Kumar’s most enduring political achievement. Over two decades, he has carefully nurtured a loyal base of women—across caste-lines—through targeted welfare schemes: free bicycles for schoolgirls, uniforms, cash-transfers for toilets, and a sense of safety that many say didn’t exist before.

In Darbhanga, a group of women at a self-help-group meeting echoed this pragmatism. “We know everyone makes promises,” said Sita Devi, 45. “But Nitishji keeps some of them. He doesn’t talk big, but he does something. That’s enough for us.”

Still, not all women agree.

In Patna city, 19-year-old Anjali Kumari, a first-time voter, said prohibition has hurt families like hers economically. “My father was arrested for selling liquor. We are poor. He had no choice. I like Tejashwi because he talks about jobs, not bans.”

This divide—between older women’s gratitude and younger women’s aspirations—could play a role in shaping Bihar’s electoral math in unexpected ways.

Disillusionment and the Desire for Dignity

In countless small conversations, a deeper yearning becomes clear—not just for employment or cash, but for dignity.

“People want to feel seen,” said Ravi Prakash, 27, who works in Noida. “We don’t expect miracles. Just recognition that our lives matter beyond elections.”

Even Tejashwi Yadav’s young supporters, while admiring his energy, express caution. “We like his style,” said Saba Parveen, a student of Patna College. “But words are easy. Our generation has grown up on promises. We are looking for proof now. But I think we need to give him an opportunity.”

In Arrah, teacher Sanjay Singh summed it up bluntly: “Announcements are not employment. Until factories come, until migration stops, these numbers—ten thousand or thirty thousand—mean little. Bihar doesn’t need more promises. It needs delivery.”

A Fear of Election “Chori”

A quieter anxiety circulates among opposition party workers. In several constituencies where contests are expected to be close, RJD and Congress workers whisper of a different kind of fear—not of losing, but of being declared losers.

“Wherever margins are tight, we are worried,” said Sanjay Yadav, a local RJD leader in Samastipur. “People have voted, and voted in large numbers. If our candidate leads by a few hundred votes, who knows what will happen during the final rounds of counting? We just hope the results reflect what people have actually voted.”

“We have fought this election with heart. The record number of voter turnout shows that,” he said. “But till the last EVM is opened, nobody will relax here.”

Such apprehensions, though unsubstantiated, reveal a telling truth about Bihar’s political moment—that even as people debate promises and personalities, trust in institutions feels stretched thin. Yet it is precisely this mix of suspicion and hope that has driven people to participate more actively than before.

As the dust settles on Bihar’s highways and campaign songs fade into silence, one truth endures: the people here have mastered the art of waiting. They have waited for roads, jobs and justice—yet still turn up at polling booths with the patience of those who believe democracy, however frayed, can deliver. In a land where politics often feels like theatre, the audience now watches with sharper eyes. This time, Bihar’s voters seem determined to decide not by applause, but by accountability.

Whatever the verdict, the high voter turnout shows that Bihar’s electorate, despite fatigue and mistrust, continues to invest faith in the democratic process. The women who lined up before dawn, the youth who travelled home from cities to vote, the workers who still hope for jobs—together they have turned cynicism into participation. Between Nitish’s promises of dignity, Tejashwi’s call for jobs, and the murmurs of mistrust in the system, voters have cast their ballots with quiet determination in the first phase of polls. Whether those votes bring change or continuity, the message is unmistakable: people are listening to every promise, but this time they expect delivery, not drama.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Mohammad Ali is an award-winning journalist, based in Delhi. He is senior associate editor with Outlook.

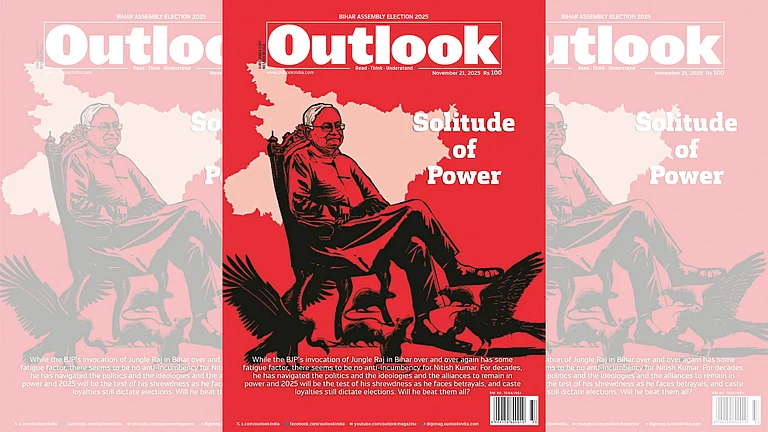

This story appeared in print as 'Nitish vs Tejashwi As Voters Demand ' in Outlook’s November 10 issue Solitude Of Power, in which we trace Bihar’s enduring political grammar, where caste equations remain constant, alliances shift like sand, and one man’s survival instinct continues to shape the state’s destiny.