Dular Chand Yadav, who supported the Jan Suraaj Party candidate against rival strongmen Anant Singh (JD-U) and Suraj Bhan (RJD), was killed allegedly by Singh’s associates, leading to Singh’s arrest amid rising fury in the region.

The incident highlights Bihar’s long-standing nexus between crime and politics, with political violence deeply rooted in the state’s history and often resurfacing during elections.

The broader reflection links this culture of political bloodshed to a historical pattern — from ancient monarchs like Ashok and Aurangzeb to modern political assassinations worldwide — illustrating the enduring connection between power and violence.

Voting in Bihar is never without bloodshed. The first phase of voting concluded on November 6. Just a week before that, 75-year-old Dularchand Yadav, an old strongman of the Mokama Assembly constituency, was murdered on October 30 while he was campaigning in support of Prashant Kishor’s Jan Suraaj Party candidate Priyadarshi Piyush in Khushal Chak area under Bhadaur police station of Mokama Assembly constituency.

Yadav was never an MLA, but his status and fear were no less than that of any MLA. In this Assembly election, in the fierce battle between two powerful strongmen in Mokama—Anant Singh and Suraj Bhan—Yadav, the older strongman, was campaigning in support of the Jan Suraaj candidate.

While Singh was the candidate from Janata Dal (United), former MP Suraj Bhan belongs to Lalu Yadav’s party, Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD).

Yadav’s murder became a turning point in the Bihar election. An FIR was filed based on the statement of Yadav’s grandson. Five people, including two nephews of Singh, were named in it. It is clear that anger against Singh has erupted in the entire area. Enraged by the murder of Yadav, the Yadavs raised a furious slogan—“Until Anant’s blood is shed, there will be no peace for the Yadavs”. Amid widespread anger against Singh in the area, Patna police arrested him late at night on November 1. He was brought to Patna Police Lines under tight security. Political pundits were constantly predicting bloodshed in the run-up to the second phase of the Bihar Assembly elections on November 11. Bihar is a “soft state” when it comes to murder. This unfortunate state, which has been a victim of the culture of political murders since before independence, has not been able to free itself from the irony of the culture of murder till date.

History is like a sleeping lion. It is dangerous to wake it up. But sometime or the other, it has to be awakened. To trace the history of criminalisation of politics is like waking up the sleeping, bloodthirsty lion.

When did criminalisation of politics start? After all, what was the need to criminalise politics at all? When will the general people be free from such criminalised politics? These and related questions have been raised for decades not only by the people of India but by the people all over the world. The fact is that since time immemorial, violence has been associated with power. Emperor Ashok the Great, the champion of Dhamma, ascended the throne after a bloodbath of his own brothers. It is another thing that history has been silent on Ashok’s heinous crime. This is probably because the emperor’s brothers were moral degenerates and hence unworthy of the throne.

Similarly, king Ajatshatru of Magadh and Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb killed their respective fathers for power. History is replete with such examples. In ancient times, tribes also followed this system. Only a person with extraordinary striking capacity could become the chief of the tribe. Even after the advent of civilization, power and violence continued to be inter-linked. With modernisation came industrialisation and a systematic established form of education. It was then that violence for gaining power came in for strong condemnation. Growth of modern progressive ideologies, like the concept of equality, further discouraged violent politics. But the negative features of power kept on surfacing from time to time, revealing that the interdependent relation between violence and power remained unbroken. Critics and opponents of violent monopolisation of power were being silenced forever and it became an accepted fact that only those who had violent means at their disposal could afford to remain in power and politics. As a result, the idea of ‘violence-free politics’, which emerged sharply with the growth of modern education and industries, gradually vanished into thin air. This adversely affected both education and industrialisation, as these were the medium which were primarily responsible for creating a social awareness in the direction.

Eminent political leaders throughout the world have been falling victims to criminalised politics. In the nineteenth century, US President Abraham Lincon was brutally murdered at a theatre. In the twentieth century, another American President John F. Kennedy’s sensational murder was followed by that of his younger brother Senator Robert Kennedy. Another heinous political murder in US was that of Martin Luther King, also known as the ‘American Gandhi’.

In the past few years, murders of important world leaders in unusually daring manner has sent shockwaves. President of South Korea, Park Chung Hee; President of Afghanistan, Nur Mohammad Taraki’; President of Egypt, Anwar Sadat; President of Bangladesh, Zia-Ur-Rahman; President of Lebanon, Bashir Gemayel; deposed Prime Minister of Grenada, Maurice Bishop, President of Sri Lanka, Ranasinghe Premdasa and Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin were murdered and left a trail of questions.

In India, political murders began soon after Independence, throwing to the wind all the cherished values embodied in our Constitution. January 30, 1948 was one of the saddest days for the country when Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated. The murder of Prime Minister Mrs Indira Gandhi on October 31, 1984, by her own bodyguards, had all the features of medieval cruelty. The assassination of another former Indian Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi, on May 21, 1991, proved the extent to which Indian politics had become criminalised. Earlier in 1975, Railway Minister in Indira Gandhi’s Cabinet, Lalit Narayan Mishra, was murdered. Besides this, many more politicians, social activists and others fell victim to armed politics.

Punjab’s present politics of terrorism germinated in 1960s, when the state’s powerful Chief Minister Pratap Singh Kairon was killed on February 6, 1965. After three decades, in 1995, another Chief Minister of Punjab, Beant Singh, was done to death by terrorists. Across the border, in Pakistan, it’s the same story. Liaquat Ali Khan, the first Pakistani Prime Minister, was murdered in full view of the public during a rally. Similarly, in Bangladesh, the leader of the Liberation Movement and the first President, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, and his entire family was done to death. In the last few decades, the process of criminalisation of politics has been so galvanic that it has sent shockwaves all over. In various states of India, the naked dance of criminalised politics went a pace. Politics in Uttar Pradesh has been under the way of ace criminals and history sheeters. As a result, it is a much-discussed state for its political crimes. Gorakhpur, one of the important districts of the state, has carved notoriety as ‘Chicago of India’.

The BBC has described it so because of the unending political crimes here. Gorakhpur was panic-stricken due to the bloody confrontation between the two leading mafia dons—Harishankar Tiwari and Birendra Pratap Shahi. This battle of the mafia groups has taken the lives of more than two hundred people.

This criminal confrontation took the life of Ravindra Singh, a member of the UP Vidhan Sabha. He had won from the Kauriram Vidhan Sabha constituency on the Janta Party ticket in 1977. Later, these two underworld kingpins became respected members of the UP Vidhan Sabha. The UP Vidhan Sabha saw a number of criminal politicians of dubious reputation as its honourable members. UP Vidhan Sabha members Nazir Ali, Laturi Singh, Ramakant Yadav and others figured prominently in police files because of their criminal activities. Ramakant Yadav, a prominent MLA, figured in the controversy surrounding the death of Jungli Prasad Bharti, an engineer of Jaunpur. Rizwan Zaheer, an independent MLA from Tulsipur in Gonda, was also involved in several criminal cases. Same was the case with Doodhnath Yadav, an MLA from Madiahu in Jaunpur. Similarly, Durga Yadav, an MLA from urban constituency of Azamgarh, Omprakash Gupta, MLA from a Vidhan Sabha constituency in Sitapur, Shamiullah Khan, MLA from one of the constituencies in Gonda district, Krishna Kinkar Singh, MLA from Captainganj in Basti district, well-known strong arm tactician, MLA D. P. Yadav, Rampal Verma, Babulal Tiwari and many other highly controversial politicians with dubious records filled the UP Assembly. Mitra Sen Yadav, the Communist member of Parliament from Faizabad, had a string of crimes of his credit. Etawah is probably most notorious for political crimes. This place has been the battleground of two political heavyweights—Mulayam Singh Yadav, a former Chief Minister of the state, and Congress stalwart Balram Singh Yadav. The warring leaders have made Etawah a haven for criminals.

Everything is for sale in Bihar. Even integrity. Ages back, Buddha had said Bihar is threatened by three things—fire, water & internal strife. Today, the land is threatened by its very own.

Some famous political families of Uttar Pradesh have figured prominently in shady political deals. In Lucknow, Mangalapati Tripathi, the youngest son of Pandit Kamlapati Tripathi, was involved in the mysterious death of a forty-two-year-old Lady Vimla Rastogi. On October 25, 1987, Saroj Verma, the daughter of former Prime Minister Chaudhary Charan Singh and a Lok Dal MLA, committed suicide. On July 28, 1988, famous badminton player Syed Modi was shot dead in broad daylight. The prime suspect was Sanjay Singh, related to V. P. Singh, former Prime Minister, through marriage and was active in UP politics for long. He was a minister in Chandra Shekhar government at the Centre. Balai Singh, the main co-accused in the Modi murder case, died under mysterious circumstances on February 27, 1991. Many members of UP Legislative Assembly were murdered one after another. Some prominent Legislators to lose their lives at the altar of political crime were Bilayati Ram Katyal of Congress (1), Bhopal Singh of Janta Dal (S) from Meerut, Sharda Prasad Rawat, and others. The high speed of criminalisation transcended political barriers and affected even the state’s bureaucracy. B. B. Singh of the Indian Civil Services was involved in the murder of his Nepali maid, Bilasiya.

The case went up to the Privy Council where he was acquitted but committed suicide later. Even small states like Haryana and Tripura could not evade the inevitable grip of criminalised politics. Choudhury Devi Lal, former deputy prime minister and patriarch of Haryana politics, along with his notorious sons, brought polities to an all-time low level. Even the home of the Choudhury was not free from crime. On November 11, 1988, his (Devi Lal’s) grandson Abhay Singh’s wife Supriya died of shots fired from her own revolver. In Tripura, former Chief Minister Sudhir Ranjan Mazumdar has been accused of openly harbouring criminals like Madhusudan Saha, alias Bhola.

The political crime graph of Madhya Pradesh shows that the state is not lagging behind. On December 28, 1991, the famous trade union leader Shankar Guha Niyogi was brutally murdered. The murder of Vijay Tandon, the son of Chandranarayan Tandon, MLA representing Damoh (M. P.), had created a lot of political controversies. In 1988, Balendu Shukul, Law Minister in the Congress government, was involved in the murder of a political activist Captain Singh Solanki in the Gwalior district. In Indore, one of the famous cities of MP, the murder of a Congress leader Mohan Balliwal created a furore and quite a few BJP Stalwarts were linked to it. In Bundelkhand, another MP, Kunwar Ashok Vir Vikram Singh, alias Bhaiaraja, who was quite a political heavyweight, was known as the ‘terror of Bundelkhand’. Even the Home Minister of MP, Jaipal Singh, was terrorised by Bhaiaraja. Apart from murders, politicians have been often accused of rape and physical assault too in Madhya Pradesh. A Congress MLA, Ganpat Rao Dhurve, was accused of violating the honour of a certain Malti Shrivastava in the Legislators retiring room in Bhopal. Dhurve and his friends were conducting a drinking party there. Even Chief Ministers have not been free of such accusations. Himachal Pradesh Chief Minister Vir Bhadra Singh was also in the net. His intimate relation with Rani Bhagyawati was a much-discussed affair. In Rajasthan, a Lok Dal MLA, Jagmal Singh, was found guilty of raping a Harijan girl. Swati Lodha accused Raj Kumar Jaipal, a Congress MLA from Ajmer, of sexual assault. In 1985, the murder of Raja Man Singh, a one-time MLA from Bharatpur, had created prolonged political controversy.

In Andhra Pradesh, during the Late N. T. Ramarao government, the killing of B. Mohan Ranga Rao, a Congress legislator, had raised a lot of controversial political dust. Apart from individual murders, mass scale killing of innocent people by political-extremist groups were on the rise. Extremist outfits like the ULFA in Assam and the People’s War Group in Andhra Pradesh and others, have unleashed virtually a reign of terror in these states. In recent years, communalisation has also abetted criminalisation of politics. The state of Gujarat is a burning example of how politicians with proven communal activities have been accommodated in politics. The reference is to the riot-prone city of Ahmadabad and its communal politician, the infamous Abdul Latif, who’s involvement in the city’s riots is well known. Yet, in the Municipal Corporation elections, Latif filed his nomination for five seats and won all of them. In Karnataka, the involvement of minister C.M. Ibrahim in communal riots is well known. Political violence spread to the cultural sphere too, and quite a few artists with different branches of art became victims of criminalised politics. The brutal murder of Safdar Hashmi on January 1, 1989, is well known. Even Journalism has been dragged into the orbit of political crimes. Clearly, criminalised politics has penetrated every nook and corner of our society. The list is too long and the details too nauseating.

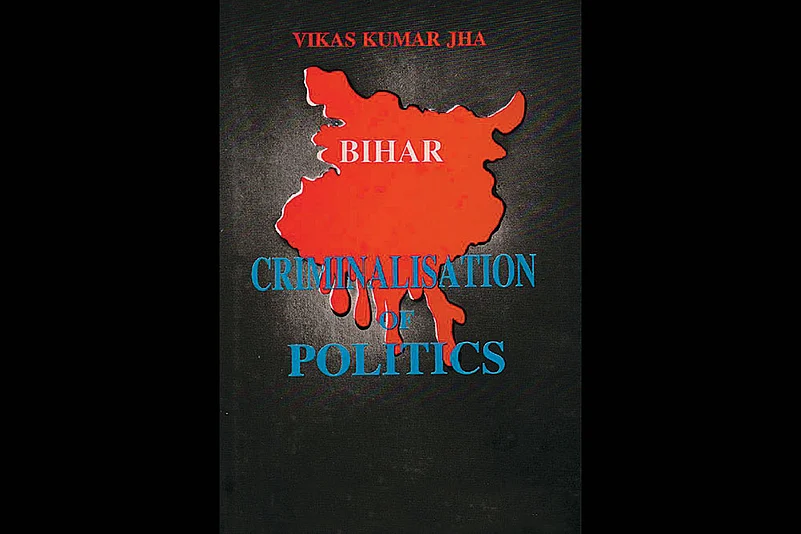

When the idea of writing a book on such a burning topic struck me, I wanted to limit myself to my own country. As I progressed in my work, the entire picture gradually became crystal clear. It was then that I realised that a microscopic study would be more meaningful. Therefore, I decided to confine my study to one state only. The choice was naturally Bihar as for almost one-and-a-half decades, I have been associated with journalism in this state. Moreover, Bihar has been in the thick of political crimes and has gained notoriety on account of it. Be it politics, bureaucracy, education or daily needs of the people, everywhere the rot is clearly visible. Everything is for sale in Bihar.

Even integrity. Ages back, Buddha had said that Bihar is threatened by three things—fire, water and internal strife. Today, the land is threatened by its very own. While writing this book, I was most positively influenced by a very down-to-earth remark of T. L. Venkat Ram Aiyyar. Aiyyar is best-known for heading the Aiyyar Commission, enquiring into corruption charges against ministers of Bihar. Aiyyar, at the beginning of his report, remarked: “I have conducted this enquiry not out of fear of any man but out of fear of God”. How well I have been able to deal with a serious topic like criminalisation of politics in Bihar is for the readers to judge. However, I must admit that while writing this book, I was immensely influenced by Aiyyar’s remarks. In my own word: “I have written this book not out of fear of man but out of fear of God.” Actually, it is the ‘fear of man’, which is responsible for the utter misfortune and abject misery of Bihar.

Many people have helped me in my venture. Without their constant co-operation and encouragement, this book would not have seen the light of the day. Thanks are due to many. I would particularly like to thank Sri Aloke Mitra, Chief Editor, of ‘Maya’, a pillar of Hindi Journalism. It is he who taught me to be a God-fearing journalist. I would like to thank specially Shri Babulal Sharma, the joint editor of Maya, who has been more of an elder brother than a professional colleague and tirelessly goaded me to sharpen my journalistic writing. Among my colleagues, I cannot help thanking profusely Ratindra Nath, who helped me to take note of every minute detail. I am thankful to my colleague Prashant also. Thanks are due to Gautam Adhikari, Sanjeev Banerjee and Santosh Kumar for their valuable contributions. Finally, I am greatly indebted to Sunil Jha, who is like a younger brother, for carefully going through the manuscript and sharing with me the pangs of anxiety and joy while writing this book. While submitting this book to my readers, I am unable to decide whether this is really an occasion for rejoicing? To be honest, such moments bring joy and satisfaction to a writer. But to write such crude facts about one’s motherland is a calamitous task. May God protect all creative writers from it.

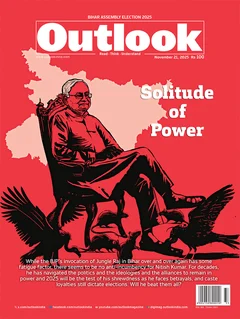

(This story appeared in print as Katta Culture in Outlook’s November 10 issue Solitude Of Power, in which we trace Bihar’s enduring political grammar, where caste equations remain constant, alliances shift like sand, and one man’s survival instinct continues to shape the state’s destiny.)

(An excerpt from Criminalisation of Politics, by Vikas Kumar Jha)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Vikas Kumar Jha is a journalist and an author