In 1990, for the first time, the number of Other Backward Classes (OBCs) MLAs (117) surpassed the number of upper caste MLAs (105).

The voting percentages in these elections were the highest since Independence—in 1990, it was 62.04 per cent, in 1995, 61.79 per cent and in 2000, 62.57 per cent.

This remarkable turning point in the political landscape of Bihar was the most important feature of the so-called ‘Jungle Raj’.

The social composition of the Bihar Legislative Assembly underwent a decisive change in the 1990s. In 1990, for the first time, the number of Other Backward Classes (OBCs) MLAs (117) surpassed the number of upper caste MLAs (105). This trend further strengthened in 1995, when the number of OBC MLAs jumped to 161, and the number of upper caste MLAs slipped to just 56. This decisive shift got reflected in the subsequent Lok Sabha elections as well—in 1991, the number of OBC candidates elected was 24, while the number of upper caste candidates elected reduced to just 10. In 1996, the numbers were 23 and 13 respectively. Remember, the voting percentages in these elections were the highest since Independence—in 1990, it was 62.04 per cent, in 1995, 61.79 per cent and in 2000, 62.57 per cent.

Hence throughout the 1990s, the ruling party enjoyed a fairly good popular support. (Between 1951 and 1985, the voting percentage moved between 39.5 per cent and 52.79 per cent. After 2000, the voting percentage dropped again and moved between 45.85 per cent and 57 per cent.)

This remarkable turning point in the political landscape of Bihar was the most important feature of the so-called ‘Jungle Raj’. The four hitherto dominant upper castes were replaced by the four emerging socially and educationally backward classes of Yadav, Kurmi, Koeri and Bania. Needless to say that in this rise of the OBCs, the representation of the Extremely Backward Castes (EBCs) was meagre.

There was a marginal increase in the number of their legislators—eight in 1990 and 17 in 1995. But the political importance of the EBCs grew in the later years of intense political mobilisation. However, the radical change in the social balance of forces galvanised the EBCs, and a spate of rallies of these castes swept the streets of Patna in the 1990s.

This decisive marginalisation of savarnas in the state assembly and the Lok Sabha was so shocking for the upper castes that for them the 1990s stuck in their memory as the Dark Age—as the Jungle Raj. For the ruling savarna elites, the 1990s was all about crime and corruption, and the representative face of this transformation, Lalu Yadav, was the villain, never to be forgiven.

This radical shift in the political landscape of Bihar was the logical outcome of four decades of social, economic and political movements led by the socialists and the communists involving agrarian labourers, poor and marginalised communities, Dalit and OBC students and youth, and of course, the emerging upwardly mobile and relatively prosperous OBC peasants, ready to take over the reins of power in rural areas.

Humankind has not yet found a ‘civilised’ way of social transformation. In the wake of the vital change in the social balance of forces, violence ensued; killings and counter-killings took place; and, savarna private senas indulged in the massacres of Dalits and other deprived communities. Here, we cannot go into the details of these violent incidents. Following the weakening of the upper caste semi-feudal hegemony, a kind of anarchy prevailed. This anarchy felicitated the rise of social rebels in various zones of the state as well as activists and cadres from among the Dalit, OBCs and EBCs. Many panchayat, block and district level present-day leaders—now in their 50s and 60s—of various parties were products of the ‘Jungle Raj’.

They mostly populate the lower and middle-level ranks of the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD), the Janata Dal-United (JD-U) and the Left parties. Some sections of them have been co-opted by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) as well.

Dons (Bahubalis) were part of Bihar’s savarna feudal society since early times—apart from indulging in various criminal activities and creating terror in their areas of operation, they were used by landlords against their rivals. During elections, they were engaged in booth capturing and bogus voting. For instance, in Begusarai, Kamdev Singh, a Bhumihar don, was frequently used by Bhumihar politicians during elections in the 1960s.

Upper caste landlords’ oppression and violence gave birth to resistance by Dalit and OBC rebels who took to arms and resorted to counter the violence. In the course of time, these rebels emerged as popular heroes of their caste and had to live underground.

Mohan Bind of Kaimur, or Kailash Mandal of Bhagalpur diara (floodplains) are examples of some of the social rebels in the 1980s. Many upper caste dons later joined political parties and became MLAs and MPs; they frequently changed their political affiliation to maintain their hold over their areas and carried on their activities. Parties of various hues have been quite generous in accommodating these Bahubalis in their fold for their narrow interests.

Dalit and OBC social rebels mainly joined the RJD, the JD-U, the Lok Janshakti Party (LJP) and the Left parties. At the same time, the Bahubalis and social rebels are a class apart, and they cannot be treated at par. Since every society has some sort of anarchy in its inner core, a progressive one, while suppressing the Bahubalis, accommodates and rehabilitates social rebels in its fold.

Bihar’s economic turnaround very much depends upon reversing this trend, and mobilising the energy and intelligence of lakhs of Bihari youth—particularly the Dalit, the OBCs and women—in rejuvenating the state’s productive potential. This is also needed to prevent participation of these forces in anti-Muslim mobilisation.

Experience shows that Bihar cannot imitate western or southern India’s model of development, or waste its time and energy in courting corporate houses for investment. Over the years, corporate houses have developed a vested interest in keeping Bihar a supplier of cheap labour. Bihar has to find its own path of development. The movement of social democracy and social justice needs to be combined with co-operative social economy of the workers, peasants, artisans, and all the stakeholders in different fields.

(Views expressed are personal)

Prasanna K. Choudhary is a freelance writer and author of a few books on Bihar in Hindi

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

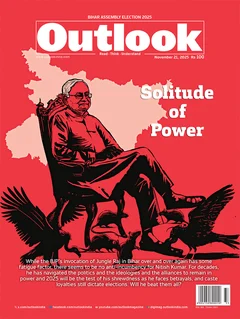

This story appeared in print as 'Bahubalis And Social Rebels' in Outlook’s November 21 issue Solitude Of Power, in which we trace Bihar’s enduring political grammar, where caste equations remain constant, alliances shift like sand, and one man’s survival instinct continues to shape the state’s destiny.