Summary of this article

The Insurance Laws (Amendment) Bill, 2025, by raising the FDI cap to 100%, signals a deeper neoliberal shift and recasting insurance from a public welfare function into a market commodity.

Reduced entry barriers for foreign insurers and reinsurers may increase competition but also heighten risks to financial stability and consumer protection.

Claims of expanded coverage mask structural realities: with nearly 90% of India’s workforce in the informal sector and public health spending remaining chronically low.

private and foreign-controlled insurance is likely to favour urban, salaried groups while shifting healthcare costs and risks onto households rather than providing genuine social security.

The Modi government’s Insurance Laws (Amendment) Bill, 2025—marketed under the slogan “Sabka Bima, Sabki Raksha”—is presented as a progressive reform aimed at expanding insurance coverage and achieving “Insurance for All by 2047.” The centrepiece of the bill is the decision to raise the Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) cap in insurance from 74 per cent to 100 per cent, allowing full foreign ownership of insurance companies operating in India.

On paper, the stated objectives sound unexceptionable: greater competition, technological innovation, deeper insurance penetration, and consumer choice. But beneath this technocratic vocabulary lies a far more consequential restructuring. The bill marks another decisive step in the neoliberal transformation of the Indian state—from guarantor of social security to facilitator of private markets—and recasts insurance from a public responsibility into a commodity to be bought and sold. It also sends a clear message to global capital: India is open for extraction, even in sectors essential to social welfare.

The Real Constituency: Global Capital, Not Indian Citizens

The increase in the FDI cap is not a mere technical adjustment. It is an ideological declaration. By eliminating the requirement of Indian majority ownership, the state signals that concerns about national control, long-term accountability, and public purpose are subordinate to the imperative of attracting foreign capital.

This signalling must be read against the backdrop of India’s worsening macroeconomic situation. The rupee has slid to historic lows, foreign exchange reserves are under pressure, and the current account deficit continues to widen. With domestic savings declining—from 33.7 per cent of GDP in 2011–12 to around 30 per cent in 2023-24—the government is scrambling for external capital. Instead of addressing the structural reasons for this decline—stagnant wages, agrarian distress, rising inequality—it has chosen the easier path of opening ever more sectors to foreign investors.

Insurance is particularly attractive to global finance. India’s insurance penetration as a share of GDP stands well below global norms—about 3.7 per cent in the latest accounting, compared with roughly 7 per cent globally. For multinational insurers facing saturated markets in the West, India represents a vast, underinsured population and a long-term stream of premium income. The bill thus offers global corporations a new frontier of accumulation, not by creating productive capacity but by capturing household savings.

The timing is revealing. The insurance bill is part of a broader pattern that includes opening nuclear energy to private players, centralising and commercialising higher education, and persistent pressure to privatise public sector banks. Together, these measures reflect a consistent policy orientation: every sphere of social life—energy, education, health, old age—is to be reorganised as a market.

Lower Barriers, Higher Risks

The bill further reduces the Net Owned Funds requirement for foreign reinsurers from Rs 5,000 crore to Rs 1,000 crore—an 80 per cent cut. This dramatically lowers entry barriers and allows thinner-capitalised foreign players to operate in India. While this is presented as encouraging competition, it raises serious concerns about financial stability and consumer protection.

India is highly vulnerable to climate-related disasters, pandemics, and economic shocks. When catastrophic claims arise, will these lightly capitalised firms honour their obligations—or will they exit, leaving policyholders stranded? The risk is not hypothetical. Global insurance history is replete with examples of firms withdrawing from high-risk markets once profitability declines.

The government proudly cites Rs 82,000 crore in FDI already attracted to the insurance sector. What it does not say is that insurance FDI does not build factories, generate mass employment, or enhance productive capacity. It primarily involves acquiring market share and extracting premiums. The much-invoked promise of “technology transfer” rings hollow in a sector where the core functions—risk pooling and claims settlement—do not require foreign ownership.

The Illusion of Coverage

Any serious discussion of insurance in India must begin with one fact: around 90 per cent of the Indian workforce is in the informal sector. These workers face irregular incomes, lack employer contributions, and are often one medical emergency away from destitution. For them, insurance is not a matter of product choice but of affordability and trust.

Private insurers—especially foreign-controlled ones—operate on actuarial logic. They prioritise customers who can pay regular premiums, pose low risk, and generate stable returns. This means urban, salaried, middle- and upper-class households. Informal workers, agricultural labourers, migrants, and the poor are either excluded, underinsured, or offered policies riddled with exclusions.

As public health infrastructure remains chronically underfunded—India budgeted only about 2.1 per cent of GDP on health in FY 2023—the state has steadily abdicated responsibility for universal healthcare. Even India’s own National Health Policy (2017) sets a modest target of 2.5 per cent of GDP by 2025, a goal that remains unmet. When private household and corporate spending is added, total health expenditure stood at just 3.31 per cent of GDP in 2022, barely half the global average of 6.7 per cent.

The inadequacy becomes starker in per capita terms. India spends roughly $80 per person on health annually, compared to over $14,500 in the United States—meaning India’s per capita health spending is barely 2 per cent of the US level. In such a dismal landscape of public provision, the state increasingly nudges citizens toward private health insurance. This is not an expansion of protection but a transfer of cost: healthcare risks are pushed onto households, disposable incomes shrink, and domestic savings are further depressed. Insurance premiums thus become another compulsory expense of survival—not a safety net.

Capital Inflows, Capital Outflows

There is also a macroeconomic irony at the heart of the bill. Premiums paid to foreign-owned insurers constitute invisible payments in the balance of payments. When profits are repatriated, they generate capital outflows that worsen the current account deficit. At a time when India’s trade deficit has reached record highs, creating new channels for profit repatriation appears economically perverse.

Moreover, insurance capital is often closer to “hot money” than to productive FDI. It can enter and exit markets relatively easily, responding to profitability rather than long-term developmental needs. In a future financial crisis, foreign insurers can simply stop underwriting new policies and scale down operations. Indian policyholders will have no recourse.

The “innovation” such firms typically introduce lies less in expanding coverage than in refining techniques of risk selection, claim rejection, and policy complexity. Innovation, in other words, serves profit extraction, not social protection.

Privatisation of Social Security

The deepest significance of the bill lies in its role in dismantling the state’s already weak commitment to social security. Since the 1990s, India has steadily moved away from public provision. Defined-benefit pensions were replaced by the market-linked National Pension System. Healthcare has been increasingly insurance-driven rather than publicly delivered. The new insurance bill represents the logical culmination of this trajectory.

The language has shifted tellingly—from “social security” to “insurance penetration,” from “entitlement” to “product,” from “citizen” to “consumer.” This is not semantic drift; it is ideological transformation.

When security is delivered through markets, it becomes contingent on the ability to pay. Citizenship no longer guarantees protection. Those who cannot afford premiums—the elderly poor, informal workers, the unemployed—are effectively written out. At the same time, the state absolves itself of responsibility. Instead of expanding public healthcare or universal pensions, it can point to the existence of insurance markets and claim that coverage is available.

This allows the government to keep social sector spending low. India already spends just over 3 per cent of GDP on education and barely 2 per cent on health—among the lowest for a major economy. Insurance becomes a substitute for welfare, not a supplement.

The shift toward private insurance also has long-term developmental consequences. Public institutions like the Life Insurance Corporation (LIC) have historically mobilised household savings and channelled them into infrastructure and development projects. As private and foreign insurers gain dominance, these funds will increasingly flow into equity markets and speculative instruments seeking maximum returns.

This weakens the state’s capacity for counter-cyclical intervention. During crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, public insurers could be directed to prioritise social needs—extend grace periods, expand coverage, absorb losses. Private insurers answer to shareholders, not citizens.

From Citizen to Consumer

Perhaps the most insidious transformation wrought by the bill is at the level of political subjectivity. Neoliberalism’s core project is to convert citizens with rights into consumers with choices. The insurance bill embodies this perfectly.

In a rights-based framework, inadequate healthcare or pension coverage represents state failure and invites political mobilisation. In a consumer framework, it represents an individual’s failure to choose the right product. The political terrain shifts from collective struggle to individual grievance redressal.

This framework systematically obscures structural inequality. For hundreds of millions of Indians living in poverty or precarity, “choice” is meaningless. Yet the bill’s promise of “Insurance for All by 2047” suggests that market expansion alone can solve deep-rooted social insecurity. The long horizon conveniently defers accountability. Present suffering is acknowledged rhetorically but postponed politically.

Most importantly, consumers cannot demand structural change. They can only switch providers within a system whose rules they do not control. Citizens, by contrast, can organise, vote, and demand redistribution. Depoliticising social security is neoliberalism’s greatest success—and the insurance bill advances it decisively.

If the goal were genuinely “insurance for all,” the starting point would not have been FDI liberalisation. It would have been universal public provision. It would have meant dramatically increasing health spending, building robust public healthcare, guaranteeing universal pensions, and strengthening public insurers accountable to Parliament and citizens.

It would have required progressive taxation of wealth and corporate profits to fund social security, not the commodification of risk. None of this appears in the bill, because it contradicts neoliberal orthodoxy

Conclusion: A Choice Made Clear

Insurance is not just a financial product but a social institution. In a deeply unequal, informal economy, it cannot be left to markets—least of all to foreign capital answerable only to shareholders.

As such the Insurance Laws (Amendment) Bill, 2025 is not a neutral reform. It is a political choice. It chooses global capital over domestic security, markets over rights, and consumers over citizens. It may well increase insurance penetration among those who can afford it. But for the vast majority of Indians—especially the 90 per cent working in the informal sector—it offers little protection and much illusion.

The question is not whether the bill will “work” in market terms. It likely will. The real question is what kind of society it entrenches: one where security is a citizenship right guaranteed by the state, or one where it is a commodity purchased by those with sufficient income. The bill answers that question unambiguously—and it is not an answer that serves common Indians

(Views expressed are personal)

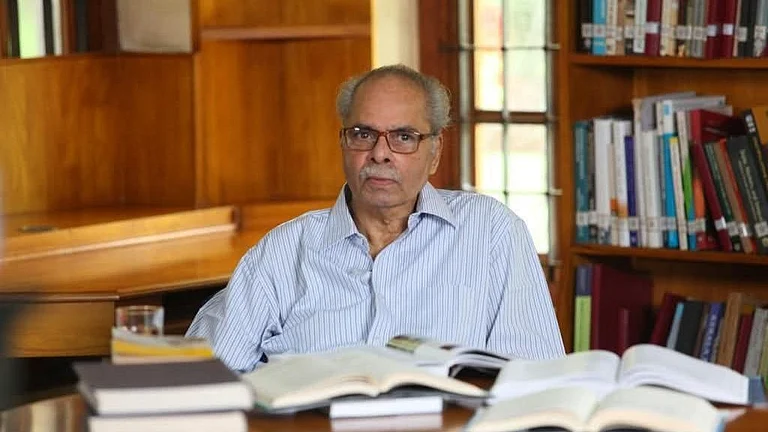

Anand Teltumbde is an Indian scholar, writer and human rights activist