Summary of this article

Ikkis is directed by Sriram Raghavan, opens the cinematic year of 2026.

The film stars Dharmendra, Agastya Nanda, Simar Bhatia, Jaideep Ahlawat, Deepak Dobriyal and a supporting ensemble.

It chronicles the life of Arun Khetarpal, India’s youngest lieutenant to be awarded the Param Vir Chakra.

Sriram Raghavan’s year opener Ikkis (2026) is a period action drama rooted in history, tracing the life of India’s youngest Param Vir Chakra awardee, Second Lieutenant Arun Khetarpal, whose bravery during the 1971 Indo-Pakistan war sealed his place in military memory across borders. The 21-year-old officer is introduced as a promising tank commander in training. Arun (Agastya Nanda) displays discipline, leadership and a romantic tenderness through his relationship with Kiran (Simar Bhatia). A future brimming with purpose appears assured, until the inevitability of war interrupts ambition with finality.

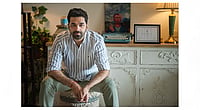

Written by Raghavan, Pooja Ladha Surti and Arijit Biswas, the screenplay unfolds across two timelines. One traces Arun’s brief but valorous service days as a cadet in Pune. The other shifts forward by three decades, following his 81-year-old father and retired Brigadier, Madan (Dharmendra) travelling to Lahore for a college reunion, using the occasion to revisit his ancestral home and the place where his son’s legacy was shaped. He is hosted by Brigadier Mohammed Naser (Jaideep Ahlawat), a former Pakistani officer whose admiration for Arun borders on the ceremonial. Naser recounts the events of that December with measured reverence, reframing the war as shared memory rather than contested history.

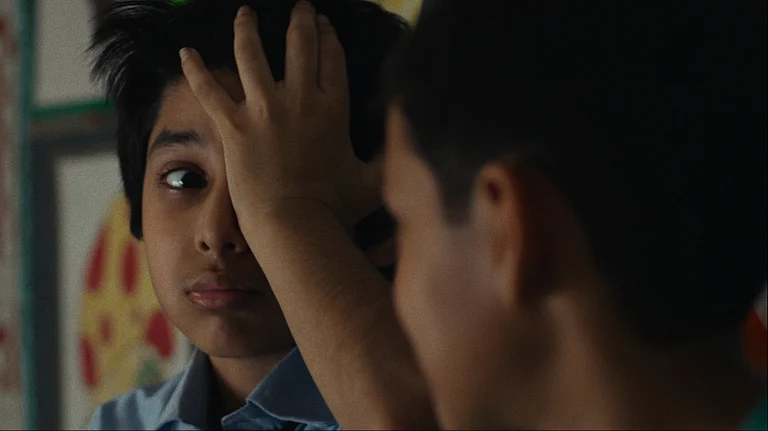

The film is deeply earnest at its core, shaped by the enduring trauma of Partition and the weight of a shared history. It gestures toward borders as fragile constructs, undone by land, rivers and history. The intent is noble and humane, retaining a collective memory tied to humanity itself. Casting works in the film’s favour, particularly in its choice of Agastya Nanda. His limitations are recalibrated into a certain unvarnished and juvenile earnestness, fitting for a young officer shaped by inherited patriotism. Arun longs to inhabit the heroism he has grown up admiring. Nanda’s mostly consistent sincerity carries the film with a faint sense of restraint. Ahlawat’s Naser is crafted as the remorseful, reverent soldier who witnessed Arun’s final moments. Despite a committed performance, the layers of guilt, shame and grief never fully surface—perhaps an intentional choice by Raghavan. Bhatia as Kiran delivers a competent turn and her character’s significance to Arun feels earned within the film’s logic, though it rarely transcends functional storytelling.

The Merry Christmas (2024) director, who is known for his apt sensibilities in capturing murder mysteries and spy thrillers has now chosen a path never taken before. An army-centred war-based film seldom elicits a different expectation than its jingoistic counterparts, but Raghavan promised not to be that filmmaker. Recently, in an interview, Raghavan explained why he would never make a Dhurandhar (2025) and that we’re living in different times. Ikkis brings with itself the weight of Raghavan’s anti-war fervour and the inevitability of its comparison with Dhurandhar. Looking at the two films separately, one can clearly tell how one focuses singly on the hypermasculine tendency to divide and conquer while the other is interested in the irreversible aftermath of war itself. Like Dhurandhar, Ikkis devotes much of its screenplay to Pakistan and pushes against the expected grammar of the nationalist genre—holding space for pride, dignity, duty and the trauma of war across both nations. Pakistan emerges as a country whose soldiers are as devoted to national security as India’s, rendered as human, vulnerable bodies that bullets scar permanently, without flattening them into caricature.

When a community’s religious chant is depicted as a threat to another, any film that does so fails to uphold the secular ethos at the heart of our nation. Unlike films such as Dhar’s Dhurandhar (2025) or Uri: The Surgical Strike (2019) that revel in glorifying valiant and triumphant victims, Raghavan seems almost perplexed, repeatedly asking “What enemy?” It recalls Yash Chopra’s Veer-Zaara (2004) in its contemplation of the human cost of separatist politics and the subtle cruelty of othering. The film’s gentlest moments emerge unexpectedly. In a scene pairing Dharmendra with Asrani, Madan encounters a Pakistani man trapped in the memories of Partition and ravaged by Alzheimer’s. Choosing patience and grace over correction, he offers a humane exchange that briefly cuts through the film’s otherwise cautious reverence.

A film dominated by bulky tanks, massive guns and camouflage uniforms rarely inspires delight for those weary of spectacle-driven militarism. Yet amid the lumbering machinery and relentless noise, a subtler tension surfaces—the creeping uncertainty of the next explosion and the dread of a comrade’s fate. The war’s quiet devastation unfolds slowly and methodically, revealing the high stakes and constant anxiety of the battlefield. Soldiers are trained to kill and dying for one’s country is accepted as duty, yet the battlefield in Ikkis, though marked by bloodshed, avoids indulgence in gore. Violence functions more as a lens into the ethical and psychological reverberations of conflict. Rather than exalting conquest, it evokes reflective empathy that unsettles instinctive nationalist instincts while revealing the subtle toll beneath the veneer of heroism. A shard of eyeglass lodged in a tree, now encased by bark, quietly signifies memory enduring through time. Another tree at Basantar marks the site where Arun drew his final breath. Dharmendra gathering soil from that spot is framed without overt sentimentality.

Arun’s romantic interest Kiran illustrates the tension between personal desire and patriotic duty, highlighting the sacrifices demanded of those who pledge their lives to the nation. The love story is moderately engaging, yet the film struggles to balance its multiple timelines and narrative threads. Arun’s cadet days emphasise relentless focus on the country, never revealing the doubt or vulnerability expected of someone so young confronting the realities of war. Similarly, Ahlawat’s Naser, a veteran who has witnessed everything, remains underutilised, offering only a surface-level reflection on guilt and the violence endured. The film’s most compelling element is Madan’s journey through past wounds and ancestral spaces, serving as a quiet but fitting tribute. His return home after this introspective passage carries a ceremonial weight, especially in light of Dharmendra’s recent passing, providing a poignant, if restrained, farewell to a legendary figure.

The score remains measured, with silence often carrying the greatest weight, though select sequences could have benefited from more nuanced musical emphasis. Ikkis is a solemn and introspective war drama. It underscores that conflicts persist in memory, unspoken bonds and lingering grief. As the world rings in the new year, this film, despite its weighty subject, positions itself as a fantastic benchmark in 2026. Though uneven at times, it attempts a mature and responsible approach to war storytelling. Overall, Ikkis proves to be a fantastic palate cleanser to the nationalist drama genre, balancing the appetite for action with the very real human costs of war.