Summary of this article

The enforcement of four labour codes will broaden worker protection, ease business operations and promoting a pro-worker labour ecosystem

The central trade unions have consistently opposed the new labour codes since their introduction, viewing them as anti-worker and designed to promote “crony capitalism” and fragile employment relations

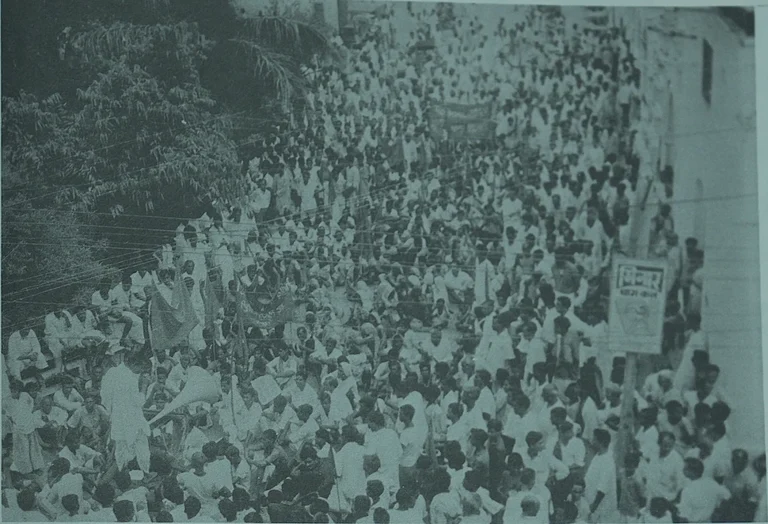

Major trade unions in India have organised nationwide strikes in protest against the implementation of the four new labour codes, arguing that they undermine worker protection and collective bargaining rights.

Indian labour struggled for nearly 200 years to end their chains of slavery, which finally succeeded in the enacting of the Trade Unions Act of 1926 (Act 16 of 926). This was a landmark in Indian labour legislation. The Act shaped the Indian labour movement and protected workers’ rights in an industrialising economy by offering trade unions legal registration and protection. The Indian Trade Unions Bill having been passed by the Legislature received its assent on March 25, 1926. After 100 years of this act, the four labour codes ushering another wave of reforms in the country are likely to be fully operational from April 1, 2026, as the ministry has begun the process for enforcing the rules under the notified law. Since labour is a concurrent subject, appropriate governments—Centre and States—will have to notify the rules under the four codes to enforce these fully across the country. The enforcement of the codes will mark the next transformative step—broadening worker protection, easing business operations and promoting a pro-worker labour ecosystem. The central trade unions have consistently opposed the new labour codes since their introduction, viewing them as anti-worker and designed to promote “crony capitalism” and fragile employment relations. Major trade unions in India have organised nationwide strikes (often called Bharat Bandh) in protest against the implementation of the four new labour codes, arguing that they undermine worker protection and collective bargaining rights. Ten large Indian trade unions have condemned the government’s rollout of the new labour codes, the biggest such overhaul in decades, as a “deceptive fraud” against workers. The unions, aligned with parties opposing Prime Minister Narendra Modi, demanded in a statement that the laws be withdrawn ahead of the nationwide protests they plan to hold.

Nature Labour Struggles Before Trade Unions

Even before the formation of any trade union, there have been various forms of labour protest activities against low wages, long working hours and poor condition of work environment in the cotton and jute industries, in the railways, mines, ports and docks, mint and presses, plantations and other non-factory concerns. The earlier record of worker protest was in 1862 when about 1,200 railway workers went on strike in Howrah station. In 1877 and 1882, textile workers in Nagpur and Bombay went on strike for longer period for better wages. Though detailed records of these protest activities are not available, the Bombay strike is argued to be the beginning of the labour movement in India. From time to time after that, sporadic and short-lived stoppages of work were reported from factories and textile mills in Bombay, Calcutta and Madras.

By the 1890s, strikes became a frequent activity for industrial workers in India involving more and more workers due to low wages, bonus, rise in foodgrian prices and retrenchments. The main reason was that there was no such stable class as industrial labour. Labour in India was still essentially agricultural and village-based. They came to the cities for employment in industries, and when they found that the conditions were not to their satisfaction. So they thought of returning to their native villages, but stayed on in towns and organised themselves to put up a fight to improve their working conditions. Labour leadership in that period mostly consisted of well intentioned social workers, who were mainly guided by humanitarian considerations. They were deeply distressed at the miserable conditions in which the workers had to live and work. They were therefore prompted by a feeling of kindness and sympathy, rather than rendering justice to labour as partners in production. Such an approach did not help in the building up of a vigorous, militant trade union movement. Since the early period, the movement was dominated by this philanthropic type of leadership and the leadership of the Indian National Congress. Narayan Meghaji Lokhande was the father of trade union movement in India. He is remembered not only for ameliorating the working conditions of the textile industry in the 18th century, but also for his courageous initiatives on caste and communal issues. Narayan Meghaji Lokhande was a prominent colleague of Mahatma Jyotiba Phule and a member of Satyashodhak Samaj.

Lokhande is acclaimed as the father of the Trade Union Movement in India. From 1880 onwards, he took over the management of Deenbandhu, which was published from Mumbai. Shasipada Banerjee was a teacher, social worker and leader of the Brahmo Samaj who is remembered as a champion of women’s rights and education and as one of the earliest workers for labour welfare in India. Shasipada Banerjee was among the earliest Indians to work for the rights of the labour class in India. The Working Men’s Club, which he established in 1870, has been described as the first labour organisation in Kolkata. The Brahmo Samaj established a Working Men’s Mission in 1878 and established several schools for working men and the depressed classes and Banerjee founded the Baranagar Institute the same year. In 1870, he founded the workers’ organisation, Sramajivi Samiti, and established the newspaper Bharat Sramajivi. The Bharat Sramajivi was the first Indian journal of the working class and its circulation peaked at 15,000 copies, a remarkable number for its time. Banerjee’s contribution to the welfare and upliftment of the working class have, however, been criticised by Sumit Sarkar for being little more than 19th century middle-class interest in industrial and plantation labour, and for not going beyond the realm of philanthropy.

Others like Dipesh Chakrabarty have argued that Banerjee’s efforts aimed to create an “ideal working class imbued with bhadralok values” and to create “not only orderly, but also noiseless Bengalis for the jute mills”. During the national movement period, Lokmanya Tilak was active with his strategy of freedom. There was lack consciousness of labour power during British rule. Tilak introduced the ‘Swadeshi’ movement. This was a new movement that appeared in the national life of our country. The ‘Swadeshi’ movement and the agitation against the partition of Bengal (1905) provided a favourable atmosphere for the growth of the trade union movement in British India. The six-day political strike by the workers of Bombay in 1908 against the judgement sentencing Lokmanya Tilak to six years imprisonment was considered a landmark in our labour movement. A new consciousness started developing among the workers.

On issues related to price rise, declining real wages, bonus, and shortage of food stuff during the First World War, workers of cotton textile mills in Bombay called a general strike in 1920. The situation was similar in other centres of industrial activity.

Early Trade Union Movement: The Role of Women

The second stage of trade union development started after the end of World War I that laid the foundation for a strong trade union movement in the country. This means that after the First World War, a major external factor that also influenced our working class movement was the Russian Revolution. The first organisation to be formed on the lines of a modern trade union was the Madras Labour Union, founded in 1918. About this time, a trade union was formed in Madras that was called the Madras Labour Union. It was formed by B.P. Wadia under the leadership and guidance of Annie Besant.

Anasuya or Anusyabehn Sarabhai was a pioneer of the women’s labour movement in India. She founded the Ahmedabad Textile Labour Association (Majdoor Mahajan Sangh), India’s oldest union of textile workers, in 1920 and Kanyagruha in 1927 to educate girls of the mills. Also, she was a beloved friend of Mahatma Gandhi who considered her “pujya” ("Revered") during his initial struggle of the Indian Independence Movement and as well as helping him establish his ashram at Sabarmati. Anusuyaben Sarabhai was the daughter of a mill agent in Ahmedabad. She had visited England and seen for herself the functioning of trade unions there. On her return to India in 1914, she began working among the textile workers and the poorer sections of the society in Ahmedabad. She established schools and welfare centres and worked for the betterment of the workers and poor people. The workers soon learnt to trust her as friend, philosopher and guide; and whenever they were in difficulty, they looked to her for assistance. It is interesting to note that the leadership for the first real trade union organised in the country was provided by a woman. The strike too was a success and the workers got a wage increase. In 1917, workers of Ahmedabad mills resorted to a strike to secure an increase in wages. Anusuyaben provided the leadership for the strike. December 4, 1917 is an unforgettable day in the annals of the trade union movement of India, more particularly Ahmedabad. The Textile Labour Association in Ahmedabad was founded in 1920 under the guidance of Mahatma Gandhi.

The year 1919 witnessed another significant development at the end of World War I—the formation of the International Labour Organisation, which was the labour wing of the League of Nations. India was one of the founder-members of the International Labour Organisation, chiefly because of the great influence wielded by Great Britain in international affairs following its victory in the war. The International Labour Organisation is a tripartite body and Indian labour had to be represented on it. It was primarily to make such representation possible that the creation of an all India organisation of trade unions was thought necessary. The All India Trade Union Congress was the result.

Organised Trade Union Movement1920-1929: A Golden Decade of Trade Union Movement

The most important incident in the history of Indian labour movement was, however, the formation of the All India Trade Union Congress (AITUC) in 1920 as a national body to coordinate trade union movement throughout the country. The All India Trade Union Congress was formed on October 31, 2020, Lala Lajpat Rai was elected the first President of the AITUC. The AITUC received lot of support from the Indian National Congress. By that time several unions were formed in Bombay, Calcutta and Madras. According to a rough estimate, there were 125 unions in India by 1920 consisting of 2,50,000 members even though many of those were temporary members. Interestingly, the leaders of the trade union movement were also the leaders of the nationalist movement. The trade union movement became a part of the wider struggle and gained its strength and vitality from the latter. The trade union movement in India has, therefore, assumed a political character from the very beginning. In spite of workers’ concern for immediate economic gains, mainly wages, trade union struggles in India were influenced by anti-colonial and anti-imperialist politics which broke from time to time under the barricade of economic demands and made the workers utilise their strike weapon to protest against colonial and imperialist repression. Ideological discussions about the role of trade unions in India started after the formation of AITUC.

Firstly, there was a complete revision of the Factories Act in 1922. An Act was also passed to repeal the Workers’ Breach of Contract Act, and provisions of a similar kind in the Penal Code. The Mines Act was also revised in 1923. The same year, the Workmen’s Compensations Act was enacted. Most important of all, the Trade Unions Act was passed in 1926. Before the Trade Unions Act was passed, labour could be charged with conspiracy for any concerted action against the employer. The Act incorporated most of the provisions of the British Labour Code. A political clause was also introduced in the Act with a view to enable Workers to secure the candidature of their respective representatives on the political bodies. The Trade Unions Act gave great encouragement to the formation of new trade unions and there was a spirit of trade union activity in all industrial centres in the country as a result of this legislation.

The AITUC approached Gandhiji with a request to affiliate his Textile Labour Association of Ahmedabad with the AITUC. He replied that he was making a unique experiment in trade union movement and that Ahmedabad was his laboratory for the purpose. He wanted the trade unions throughout the country to be fashioned after his Ahmedabad model, and would therefore wait till such a situation arose. Gandhiji said: ‘If I had my way, I would regulate all the labour organisations of India after the Ahmedabad model. It has never sought to intrude itself upon the AITUC and has been uninfluenced by that Congress. A time, I hope, will come when it will be possible for the All India Trade Union Congress to accept the Ahmedabad methods and have the Ahmedabad organization as part of the All India Union. I am in no hurry. It will come in its own time.”

The International Communist movement also gave these Indian communists the necessary ideological and monetary help. The 5th Congress of the Communist International held in 1924 gave Indian communists the following direction: “The Indian communists must bring the trade union movement under their influence. They must reorganize it on a class basis and purge it of all alien elements.”

Marxism, whatever its appeal to the people of other countries, was wholly opposed to the tradition and culture of the Indian people and therefore failed to appeal to them. It sought to preach a philosophy of atheistic materialism to the Indian people whose culture lay embedded deeply in spiritualism and even renunciation. It was, therefore, highly doubtful whether the communist movement could gain any real and lasting foothold in India at any time. Indeed, it could not have got even a temporary foothold in the country and started working on any scale but for the continuous and massive assistance from Soviet Russia even in those early days. The history of working class movement is marked by split, inter-union rivalry, state intervention in different forms and concentration of struggle in the organised sector of our economy. There were three distinct ideological groups in the trade unions federation: Communists, led by M.N. Ray and Dange; nationalists, led by Gandhi and Nehru and moderates led by N.M. Joshi and V.V. Giri. Serious differences prevailed among these three groups on important questions such as the nature of relationship between trade unions and the broader political movement, the attitude to be adopted towards British rule and affiliation to international bodies. As a result of these differences, AITUC suffered a split first in 1929 and then in 1931. By 1931, there were two more national federations of trade unions apart from AITUC. These were namely, Indian Federation of Trade Union (IFTU), formed by moderates and reformists and Red Trade Union Congress (RTUC), formed by the Communists. Later in 1935, AITUC and RTUC came together, and need for workers’ unity was again felt among all our trade unionists in the context of intensified nationalist and anti-imperialist struggles.

In 1940, such unity could be forged when NFTU merged with AITUC. In 1935, the All India Red Trade Union Congress, led by the extreme communists, merged with the AITUC, obviously as a tactical move and in accordance with directions from Moscow. Efforts were therefore set afoot to unify the trade union movement in the country by bringing back the National Trade Union Federation also, which had gone out of the AITUC at the 1929 Nagpur session and formed the Indian Trade Union Federation. It was again in Nagpur, in 1938, that a Unity Conference took place and the AITUC accepted the merger terms suggested by the National Trade Union Federation. One of the terms that facilitated merger was that no political decision should be taken, unless it commanded a two-thirds majority. Unity was finally achieved in 1940 with N.M. Joshi becoming General Secretary of the AITUC.

Independent Labour Party of India: A failed political Project

In August 1936, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar established the Independent Labor Party. The main objective of the party was the welfare of the laborers. So it was deemed as a labour organisation. In order to bring the depressed classes with the purview of the labor class, they proposed that they be referred to as the labor class instead of the Depressed Class.

It was an epoch-making event in the history of modern India when Ambedkar joined the British Viceroy’s Executive Council as Labour Member on July 20, 1942. Ambedkar truly represented the working class all his life. Once, in his childhood, he even wanted to become a mill worker. In the words of Louise Ouwerkerk, who wrote the book The Untouchables of India in 1945, says about Ambedkar that “One of the best organised Trade Unions in India is the Bombay Municipal Workers union, started by the energetic Dr. Ambedkar in 1934”. BAW, Vol-17-II: Constitution of Independent Labour Party “A new political party has been organised in Bombay for the purpose of contesting the elections in the Bombay Presidency under the new Constitution to both Chambers of the Legislature. It is known as the ‘‘Independent Labour Party” and has been formed by Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, the Depressed Classes leader. It appears that originally Dr. Ambedkar’s idea was to organise a party exclusively of the Depressed Classes. But its programme was specifically worded in terms of the needs of these Classes. But at the desire of his friends from other classes, he has consented to give a general name to the party and has worded the programme in more general terms. The Party is open to anyone who wishes to stand for election on the Party ticket and work in the Legislature in accordance with the programme formulated for the purpose.”

Succesful Labour Parties other than India

England: The Labour Party was formed by unions and left-wing groups to create a distinct political voice for the working class in Britain. The origins of what became the Labour Party emerged in the late 19th century. It represented the interests of the labour unions and more generally the growing urban working class. In all general elections since 1918, Labour has been either the governing party or the Official Opposition. There have been six Labour prime ministers. Since 1918, Labour have formed 12 governments, compared to 13 for the Conservatives within this period.

Russia: The Russian Social Democratic Party (RSDP), was a socialist political party founded in 1898 in Minsk, Russian Empire. The party emerged from the merger of various Marxist groups operating under Tsarist repression, and was dedicated to the overthrow of the autocracy and the establishment of a socialist state based on the revolutionary leadership of the Russian proletariat. After the Bolsheviks seized power in the October Revolution later that year, the RSDLP was effectively dissolved. In 1918, the Bolshevik party formally renamed itself the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks), which later became the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The RSDLP program was based strictly on the theories of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Specifically, that despite Russia's agrarian nature at the time, the true revolutionary potential lay with the industrial working class.

Australia: The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also known as the Labor Party or simply Labor, is the major centre-left political party in Australia. The Labor Party is often called the party of unions due to its close ties to the labour movement in Australia and historical founding by trade unions, with the majority of Australian trade unions being affiliated with the Labor Party. At the 1910 federal election, Labor became the first party in Australia to win a majority in either house of the Australian parliament. In every election since 1910 Labor has either served as the governing party or the opposition. There have been 13 Labor prime ministers and 10 periods of federal Labor governments.

New Zealand: The New Zealand Labour Party, a centre-left political party in New Zealand. The party's platform programme describes its founding principle as democratic socialism, while observers describe Labour as social democratic and pragmatic in practice. The party participates in the international Progressive Alliance. It is one of two major political parties in New Zealand, alongside its traditional rival, the National Party. The New Zealand Labour Party formed in 1916 out of various socialist parties and trade unions. It is the country's oldest political party still in existence. Alongside the National Party, Labour has alternated in leading governments of New Zealand since the 1930s. As of 2020, there have been six periods of Labour government under 11 Labour prime ministers. The party has traditionally been supported by the working classes.

Political Affiliation of Trade Unions:

Ideological and strategic debates among our trade union leaders continued even after Independence, and ultimately these led to the formation of several trade union centres. In May 1947, nationalists and moderates formed Indian National Trade Union Congress (INTUC), since by then the Communists had acquired control over AITUC. The Congress socialists who stayed in AITUC at the time of the formation of INTUC subsequently formed Hind Mazdoor Sabha (HMS). A few years later the HMS was split up with a faction of socialists forming Bharatiya Mazdoor Sabha (BMS), and again when there was split among the Communists, the United Trade Union Congress (UTUC) and Centre of Indian Trade Unions (CITU) were formed. Later, a splinter group of UTUC formed another federation, i.e. UTUC, Lenin Sarani. With the birth of regional parties since the 1960’s almost every regional party now has a trade union wing. Today, trade unions’ association with political parties is almost an all India feature. Even parties with sectarian or nativistic feelings started organising workers. It is argued that the ‘politics of nativism’ has helped Shiva Sena acquire a considerable presence in the trade union scene in Bombay (Gupta 1978). Short-term objectives and electoral considerations also became the tenets of trade union politics. The origin and growth of trade unionism in India is riddled with fragmented politicisation that has also led to the perpetuation of inter and intra-union rivalries (Ghosh 1988). It is therefore argued that political unionism leads to party dominance over unions, encourages outside leadership, and stands in the way of working class unity. On the contrary, non-political unionism has been held out as the only solution to the problem of trade unions (Giri 1958). There are, however, claims opposed to it. From a study of the Textile Workers’ Union of Coimbatore, Ramaswamy (1982:228) shows that politicisation provides the ‘union with a nucleus of committed members who are actually involved in union affairs and assume leadership. Without such committed members, trade unions can never become organisation of workers. The reality is that most workers in India do not feel committed enough to the union to aspire for an office. The politically committed workers are more willing to shoulder responsibility because of their double identification with the Union. Ramaswamy has found that although the unions have been started and politicised by partisan leaders, they (unions) have developed a logic and momentum of their own. A study conducted by Vaid (1965) also shows that, in general, political and socio-psychological considerations provide the greatest motivation for joining the union.

Neoliberal Period: Trade Union Movement at Dead End

The introduction of the LPG (liberalisation, privatisation and globalisation) model in India since the middle of 1980s has opened a veritable Pandora’s Box with far reaching implications for labour, their unions and management as well . In the pre-liberalised Indian society, the state maintained a complex set of labour regulations that aimed at strengthening trade unions, improving wage outcomes and increasing job security in the formal economy.

Governmental intervention to strengthen the position of workers vis-à-vis employers has led to the passing of nearly 200 labour laws by both the central and state governments. Apparently, these labour regulations have contributed to the strength of Indian trade unions by making job security, wage rate and other benefits ‘statutory compulsions’ for the employers of factories. But it may as well be argued that these laws have also made our unions and workers dependent on the Government machinery for settling any issue. The pre-reform industrial relations in India are, therefore, typically marked by third party intervention that stood in the way of a rapid growth of genuine collective bargaining. In fact, it has been argued that state regulations have perpetuated, if not also actively contributed, to a weak and divided labour movement that remained dependent on external props Problems like fragmentation and intra-union rivalry, narrow sectarianism and lack of ideological base, short-term objectives, economism and electoral considerations for trade union struggle, corrupt leadership with managerial support, etc., broadly characterize trade unionism in post-independent India. The existence of a vast pool of unorganised labour has made our unions inherently weak.

It is in such a context liberalisation has fostered, among others, new forms of industrial organization including enormous growth of information technology and informal work relations, spatial reorganizations, flexible specialisation, subcontracting, feminisation, changes in the skill levels of working ‘classes’, etc. All these have initiated qualitative changes in our industrial life today Since the introduction of the New Industrial Policy in 1991, which virtually freed the domestic investors from all licensing requirements, Government expedited the process of reducing public sector investments, closing down loss making PSUs and even selling the share of high-profile PSUs. Voluntary Retirement Scheme (VRS) and the Exit Policy were being indiscriminately adopted to retrench the organised workforce and to close down most of the sick industrial units in both public and private sectors. Government is also trying to amend the Industrial Relations Act to break down the strength of organised labour further.

It should also be noted here that some state governments like Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Karnataka have proposed to introduce ‘flexible labour policy’ applicable to the units working under Special Economic Zones. Such flexibility removes working hours’ compulsion and many other legal stipulations related to employment and management. It is due to such open or tacit state support and political encouragement for the capital and the expanding culture of ‘free market’ that trade unions now face writings on the wall. There were several instances of political, administrative, legal and police support or protections being provided to prospective investors; the Haryana Honda Motors case being the brightest one. There have also been certain attempts by the employers to shift the location of the industry from highly unionised regions, such as Kerala and West Bengal, to less militant regions or to free-trade zones Hence, even the Left parties and their governments could not take the risk of providing blanket support to trade unionism that could have antagonised the prospective investors or hamper productivity of a firm. Opposition to traditional style of militant unionism is almost common in today’s life and the greater society has little sympathy for any kind of militant unionism. Market reform has, therefore, changed the concept of work. Today, capital-intensive work organizations look lean and thin, stressing competitiveness, multiple skills, and higher productivity. Our old trade unions do not fit into this structure.

Dark Period of Indian Trade Union Movement: Dangerous Decade 2015- 2025

DIPAM: light is not lightening

Department of Investment and Public Asset Management (DIPAM) deals with all matters relating to management of Central Government investments in equity including disinvestment of equity in Central Public Sector Enterprises (CPSE's). The three major areas of its work relate to Strategic Disinvestment, Minority Stake Sales and Capital Restructuring. All matters relating to sale of Central Government equity through offer for sale or private placement or any other mode as well as strategic disinvestment of CPSE's is dealt with in DIPAM. DIPAM is a Department under the Ministry of Finance.

Disinvestments or privatisation of the public sector industries, and mass scale casualisation of labour force have further aggravated trade unions’ agony While casualisation is causing increased employment opportunities for some, it also means loss of jobs for others. On the whole casualisation displaces better-paid, more protected workers and increases insecure and low-paid employment. Today, the process of casualisation has also intensified another labour process called ‘feminisation’ of workforce in several industries. Although technical changes have eliminated many jobs traditionally performed by women, there has also been mass scale replacement of permanent male workers by casual female workers in some industries. In the Public and Private sector organised industries as a whole, the number of women workers has increased rapidly. This ‘gendering’ of jobs helps the employers to pay less and get rid of powerful protesters as well. Women workers hardly join any union activity and their image of ‘supplementary wage earner’ helps in perpetuating the myth that they are easily ‘dispensable’).

Obstacles to successful trade union mobilisation also emerge from the fact that casual and temporary workers in the informal sectors generally remain less enthusiastic about union activity. With little or no job security, they also cannot always take the risk of engaging their masters. The growing size of informal employment is a major challenge before the existing unions. The entry of subcontractors or third party between the workers and employers makes such endeavour even further difficult.

Apart from informalisation, modern electronic (henceforth ME) technologies also have caused fragmentation of the labour processes and consequent segmentation of the workers. Centralized unions with compactness now find it difficult to handle such diversities. Trade union leaders today are concerned about the effects of new technologies, but they cannot seriously oppose them. Because, technological superiority is required for any survival in the competitive market. ME technologies not only increase profitability and productivity, they also heighten the prestige and pride of the workers. Trade unions are, therefore, often seen engaged in suggesting and implementing plan and programmes of modernization. This is despite the fact that new technology causes redundancy and unemployment, and consequent shrinkage of union’s power. Again, it creates a new set of ‘elite’ workers whose interests are distinct from traditional workers. More importantly, the new technology has strike breaking and labour control capacity. All these contribute to de-unionisation, weakening of bargaining strength of trade unions and formation of independent or local trade union. The issue of technological modernization thus traps most trade unions into a vicious circle. If they oppose modernization, workers’ bargaining strength deteriorates. If, on the contrary, they give consent to such steps, management gains. The critical situation thus, becomes an ideal ground for company unionism and syndicalism.

Furthermore, the entry of global traders or TNC’s into local market has brought a new factor, international division of labour, into play. Now local disputes are to be solved internationally with the real master either hiding himself or remaining far away from the reach of any union activity. Working class then requires a new weapon to strike the far off targets. This calls for qualitative changes in the modus operandi of existing unions. In other words, trade unions’ fight against capitalism then becomes a political fight against imperialism eating into the economic (and political too) sovereignty of the nation. The expanding horizon and challenges of trade union struggle introduce both compulsions and hope for the future of working class struggle in the country.

The author is with the Centre for Informal Sector and Labour Studies, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University

(Views expressed are personal)