Once synonymous with Bihar politics, Lalu Prasad Yadav rose from humble beginnings to become Chief Minister in 1990, blending political charisma with populist flair and a unique brand of performative politics.

Lalu’s arrest of BJP leader L.K. Advani during the 1990 Rath Yatra marked a defining political moment, as his government navigated the turbulent mix of caste, religion, and power.

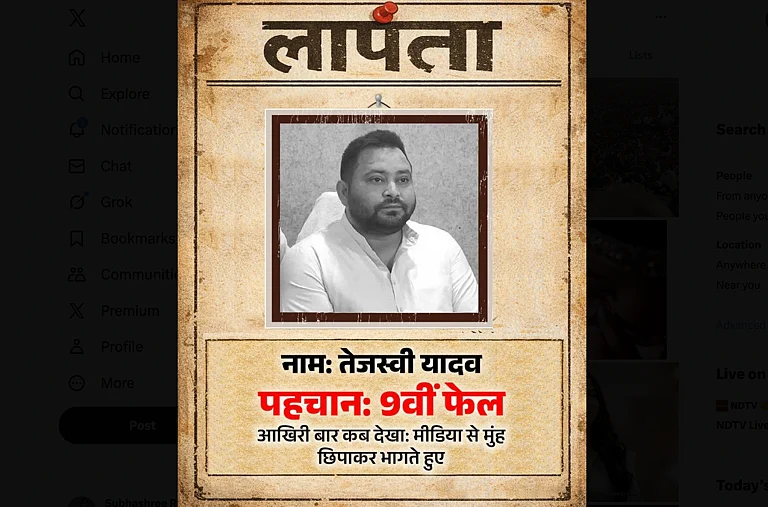

Though ousted in 2005 by Nitish Kumar, Lalu’s political and social legacy continues to shape Bihar’s identity, with his son Tejashwi Yadav now leading the INDIA bloc into the upcoming elections.

At one time, Lalu Prasad Yadav’s name was virtually synonymous with Bihar politics. He rose to prominence against formidable odds, becoming known not only for his political acumen but also for his unmistakable charisma and earthy humour. His quirks and trademark one-liners became his signature style, often drawing laughter in the Lok Sabha during his tenure as Railway Minister in Manmohan Singh’s first government in 2005.

Among his many memorable phrases, one stands out: “Jab tak rahega samosa mein aaloo, tab tak rahega Bihar mein Lalu” (“As long as there’s potato in samosa, there will be Lalu in Bihar”). The line echoed across the state in the early 2000s as the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) chief used it to charm and connect with the rural electorate during campaign rallies.

Lalu’s flair for drama was evident even at home. After being sworn in as Chief Minister, he reportedly told his mother, “Mayee hum mukhyamantri ban gaynee” (“Mother, I have become the Chief Minister”). Her dry response, documented by Mrityunjay Sharma in Broken Promises: Caste, Crime and Politics in Bihar, was, “Achcha thik ba, jaaye de, lekin tohra sarkaari naukri naa nu milal” (“That’s fine, but you still couldn’t secure a government job”).

Born in 1948 in Phulwaria village, Bihar, Lalu Prasad Yadav came from modest beginnings. Moving to Patna as a young boy, he entered student politics at Patna University, serving as General Secretary of the Students’ Union from 1967 to 1969. Mentored by socialist leader Jayaprakash Narayan, Yadav became an active participant in the JP Movement against Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s government in the 1970s. During the Emergency of 1975, he was arrested and remained in detention until 1977.

Later that year, he was elected to the Lok Sabha from Chhapra on a Janata Party ticket.

Fast forward to 1990, Lalu became the Chief Minister of Bihar, and led the party to victory in assembly elections in Bihar. As Sankarshan Thakur writes in his The Brothers Bihari, Lalu Yadav’s politics was an angry revolt against sahebdom, against the age-old order appointed by the upper-caste haves.

His troubles began after his second victory in 1995, when he was embroiled in a major corruption scandal that allegedly implicated him along with several of the state’s top bureaucrats and politicians. The case centred on the embezzlement of ₹9.5 billion, intended for purchasing cattle fodder in Bihar, which the media swiftly labelled the “fodder scam”.

Yadav was compelled to resign as Chief Minister in July 1997, but he appointed his wife, Rabri Devi, as his successor. It was widely believed, however, that he continued to wield power behind the scenes. In December 2006, Yadav was acquitted of the initial corruption charges.

That same month, after stepping down as Chief Minister, he severed ties with the Janata Dal and founded the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD), becoming its president. He was re-elected to the Lok Sabha in 1998 and later secured a seat in the Rajya Sabha in 2002.

He understood the number games, orchestrating victories in his stead even when he was not the Chief Minister. In the intervening years before he became a federal minister in 2004, he also contested and won a seat in the 2000 Bihar Assembly elections. The RJD, in alliance with the Congress and other parties, formed a coalition government, with Rabri Devi once again taking charge as Chief Minister.

As Bihar stands on the precipice of another electoral crucible next month, Lalu is once again remembered as a patron saint who has much to do with the realities of Bihar. His 15-year rule came to be defined by many things, but above all, it became emblematic of ‘Jungle Raj.’

In 2005, Nitish Kumar built his government on the backdrop of institutional decay, bureaucratic excess and the erosion of social order that had come to define Lalu’s reign. Conversely, Lalu had begun his tenure with a set of alternative promises.

Paying attention to the optics, he took his oath at Gandhi Maidan instead of Raj Bhavan, took bicycle rides to the secretariat, and had arranged Janata Darbar sessions. However, his credibility was quickly compromised, a reputation that still follows him around. As recently as 2017, a series of audio tapes surfaced, revealing that Lalu was allegedly taking instructions from his long-time confidant and notorious mafia don-turned-politician, Mohammad Shahabuddin.

The RJD continues to bear that baggage even today, two decades after being voted out of power, with Chief Minister Nitish Kumar, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and Home Minister Amit Shah routinely weaponising the term and warning voters against its return during election rallies.

However, beyond this, Lalu’s rule in the state was also characterised by several other significant events. Recovering from the 1989 Bhagalpur violence and implementing the Mandal Commission recommendations, Lalu had to deal with BJP stalwart LK Advani’s rath yatra, which began on 25 September 1990 from Somnath in Gujarat to campaign for the construction of a Ram temple at the disputed Ramjanmabhoomi-Babri Masjid site in Ayodhya.

43-year-old Lalu, who relied on Muslim voters, was just months into his position as the Chief Minister. At the time, Lalu headed a Janata Dal government in Bihar, while the party also ruled at the Centre with BJP support. Seeking to capitalise on the Ram Janmabhoomi wave, BJP president L.K. Advani launched his Rath Yatra, warning that any attempt to stop it could cost the Janata Dal its government.

On the night of October 22 1990, as Advani reached Samastipur, he was arrested on Lalu’s orders. Before leaving with officials, he wrote to President R. Venkataraman, announcing the BJP’s withdrawal of support to the V.P. Singh government.

Even though the state was saved of communal violence, under Lalu, Bihar was scarred by a brutal cycle of caste-based retributive violence between landlord militias and Naxalite groups. In just eleven years, many massacres were recorded.

Also in the 1990s, the criminality became deeply embedded within the political system itself. The 1990 Assembly elections underscored this shift, as 30 independent candidates — many of them bahubalis or local strongmen who ruled their territories through fear and impunity — won seats, often with tacit backing from those in power.

The story of Bihar’s decline in the 1990s is not merely one of political collapse but of its economically corrosive effects when the state’s per capita income plummeted. However, Lalu had already reshaped Bihar’s social fabric through his own brand of social engineering, making the state that Nitish Kumar inherited in 2005 vastly different from the one Lalu had taken over in 1990.

Before Lalu’s rise, the state was ruled and dominated by a small upper-caste Hindu elite that imposed widespread poverty, oppression and exploitation on the lower-caste Hindus and Muslims. By the time his party was defeated by Nitish in 2005, Bihar had undergone a social transformation, a deliberate process of social engineering that awakened and empowered the long-marginalised masses.

As Bihar goes to poll next month, his son and heir-apparent Tejashwi Yadav has been announced as the Chief Minister face for the INDIA bloc.