Summary of this article

The Pentagon views improving India-China relations as a threat to US strategic dominance in Asia.

India and China insist their boundary dispute is strictly bilateral, rejecting US mediation.

Renewed diplomacy, flights, and visa easing signal a cautious but deliberate rapprochement shaping Global South politics.

On December 25, 2025, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Lin Jian responded to allegations contained in the Pentagon's annual report to Congress on China's military developments. The report claimed that Beijing 'probably seeks to capitalise on decreased tension along the LAC to stabilise bilateral relations and prevent the deepening of US-India ties.' Lin's rebuttal was unequivocal: the Pentagon's report 'distorts China's defence policy, sows discord between China and other countries, and aims at finding a pretext for the US to maintain its military supremacy.' This exchange reveals something fundamental about the current conjuncture. Washington's anxiety about improving India-China relations is not rooted in concern for regional stability but in the structural imperative of American hegemony to prevent autonomous consolidation among Global South nations.

Lin Jian emphasised that China 'views and handles its relations with India from a strategic height and a long-term perspective,' adding that the boundary question 'is a matter between China and India' and that Beijing objects to 'any country passing judgment about this issue.' Crucially, this is not merely China's position. India has consistently maintained the same stance. When US President Donald Trump offered to mediate between India and China earlier this year, Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri reaffirmed India's position: 'Whatever issues we have with any of our neighbours, we have always adopted a bilateral approach to dealing with these issues.' External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar has repeatedly ruled out third-party involvement, stating that the dispute 'is a matter for the two countries to address independently.' This convergence between New Delhi and Beijing on the principle of bilateral sovereignty constitutes precisely the kind of assertion that undergirds the emerging architecture of multipolarity.

The Material Basis of Rapprochement

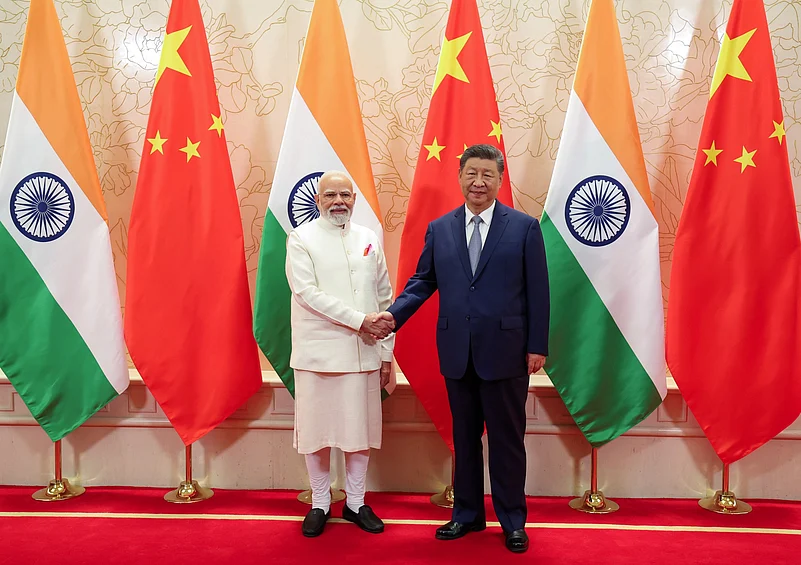

The improving trajectory in India-China relations is grounded in concrete confidence-building measures that create the material basis for sustained engagement. The September 2025 meeting between Prime Minister Modi and President Xi at the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation summit in Tianjin marked a significant inflection point. The explicit framing of India and China as 'partners, not rivals' represented language absent since before the 2020 Galwan crisis. The reactivation of the Special Representatives dialogue on the boundary question signalled a qualitative shift in approach.

Several practical measures have since given substance to this reset. The resumption of direct flights in October 2025, after a five-year suspension, exemplifies this trajectory. The direct flight services have reconnected two of the world's largest economies through direct commercial links. These are not merely logistical conveniences but represent the material infrastructure of people-to-people contact that sustains cooperative relations. The easing of visa procedures further demonstrates this movement. China's December 2025 introduction of an online visa application system for Indian nationals eliminates the requirement for in-person consular visits. India's reciprocal streamlining of business visas for Chinese professionals, reducing approval times to under four weeks, reflects mutual recognition that friction in human mobility impedes broader cooperation.

These measures embody a political choice: the choice to prioritise engagement over estrangement. They do not resolve the boundary dispute or eliminate structural competition. But they create conditions under which dialogue becomes possible and cooperation can develop. This is significant precisely because it represents an ongoing project rather than a completed transformation. The direction of travel matters enormously for the broader aspirations of the Global South.

Implications for the Global South

India and China together represent approximately 3 billion people, more than a third of humanity. Their cooperation or conflict shapes the possibilities available to the entire Global South. When the two largest developing nations manage their differences through dialogue rather than confrontation, they create space for a different kind of international order. This is why Washington finds the prospect threatening. American strategy in Asia has long relied on leveraging regional tensions to anchor allies within its security architecture. The Quad, intensified military cooperation with India, and AUKUS all reflect this logic. The fact that both India and China reject external mediation in their boundary dispute, despite their differences, demonstrates that major Asian powers can pursue their interests without subordinating themselves to American strategic designs.

The BRICS framework gains credibility from demonstrated India-China cooperation. The 2025 BRICS Summit in Rio de Janeiro, themed 'Strengthening Global South Cooperation for More Inclusive and Sustainable Governance,' reaffirmed this orientation. The bloc's expansion to eleven members, now including Indonesia, the UAE, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Iran, demonstrates the attraction of an institutional framework premised on sovereign equality rather than hierarchical subordination. The proposed SCO Development Bank, an instrument for infrastructure connectivity not indexed to IMF or World Bank conditionalities, would complement the BRICS New Development Bank. For countries seeking to break out of existing global hierarchies, these initiatives demonstrate that development need not follow Washington consensus prescriptions.

Challenges and the Path Forward

None of this suggests that substantive differences have been resolved. The boundary question remains unresolved. Mutual suspicions persist. Structural competition for influence in South Asia and the Indian Ocean region continues. Yet these challenges are for India and China to navigate through their own bilateral mechanisms, not for external powers to exploit or adjudicate. What the Pentagon report gets wrong is the implication that existing tensions justify American intervention to prevent improvement in the relationship. The shared position articulated by both China's Foreign Ministry and India's External Affairs Ministry, that boundary matters are bilateral and external powers should not pass judgment, aligns with the fundamental principle of sovereign equality. Both governments have established mechanisms for resolving their differences bilaterally and have consistently rejected third-party mediation, whether from Washington or elsewhere.

For India, a functional relationship with China offers leverage rather than capitulation. The capacity to engage Beijing constructively while maintaining other partnerships enhances strategic autonomy. India can simultaneously engage with the US and the Global North institutions, deepen ties with ASEAN, and improve relations with China. The premise that any improvement in India-China ties comes at the expense of India-US relations reveals American insecurities rather than Indian interests. The task ahead is to convert these developments into durable policy: time-bound Special Representatives meetings, transparent aviation and visa timelines, concrete banking and trade roadmaps. Peace is not sentimental; it is planned. The Chinese foreign ministry statement today, demonstrates that both India and China, whatever their differences, recognise the value of planning it together, and that both reject external interference in this process. For those committed to Global South solidarity, this represents a positive step toward the multipolar world that the current conjuncture demands.

Atul Chandra is the Co-Coordinator of the Asia Desk at the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.