Summary of this article

The century of the Communist movement in India is a history of sacrifice, of ideological battles, of tremendous victories and painful defeats.

In April 1957, E. M. S. Namboodiripad took oath as Chief Minister of Kerala, leading the first democratically elected Communist government outside the Socialist Bloc.

The fundamental questions that animated Indian Communists remain urgent: Who controls the land? Who owns the factories? Who makes the decisions that shape our collective lives?

The Communist movement in India is now 100 years old. Whether one dates this from October, 1920, when Indian revolutionaries like M. N Roy, Abani Mukherjee and other Indian revolutionaries gathered in Tashkent to formally establish the Communist Party of India, or from December 1925, when Communist groups came together at the Kanpur conference in 1925 to constitute an all-India party, the fact remains that for over a hundred years, Communists have been an integral part of Indian political and social life. The Communists have fought colonial rule, built mass organisations of workers and peasants, governed states, resisted communal fascism and kept alive the dream of a society free from exploitation. The century of the Communist movement in India is a history of sacrifice, of ideological battles, of tremendous victories and painful defeats. It is also a history that speaks directly to our present moment, when the Right-wing Hindutva forces seek to shape India with their imagination and when the predations of global capital intensify the misery of the common people.

Any serious engagement with the history of Indian Communism must begin by acknowledging a historiographical debate that reflects the deeper questions about the nature of the movement itself. The Communist Party of India (Marxist), popularly known as the CPI (M), maintains that the party was founded on October 17, 1920, in Tashkent. This establishment was assisted by the Communist International. The Communist Party of India, popularly known as the CPI, on the other hand, considers the December 1925 conference in Kanpur as the authentic founding moment, when Communist groups already working inside India came together to establish an organised all-India party with a constitution and elected leadership.

This is not merely an archival dispute for historians to settle. The Tashkent formation represented the organic connection between Indian liberation and proletarian internationalism. It recognised that the struggle against British colonialism was inseparable from the worldwide movement against imperialism. The Kanpur conference, meanwhile, represented the rooting of the Communist organisation in Indian soil among workers and peasants of India. But one must understand that both these moments were necessary stages in the development of a movement that would eventually mobilise millions. The dialectical unity of these two currents, international solidarity and indigenous mass organisations, has defined Indian Communism throughout its existence.

Forged in the Colonial Fire

The British colonial administration understood, perhaps better than some nationalists of that era, the revolutionary potential of the Communist ideas among the India’s toiling masses. The colonial state responded with characteristic brutality. The Peshawar Conspiracy Cases, The Kanpur Bolshevik Conspiracy case and the most prominent, the Meerut Conspiracy case of 1929 to 1933, saw leading Communists prosecuted for seeking, in the words of the chargesheet ‘to deprive the King Emperor of his Sovereignty of British India, by complete separation of India from Britain by a violent revolution’.

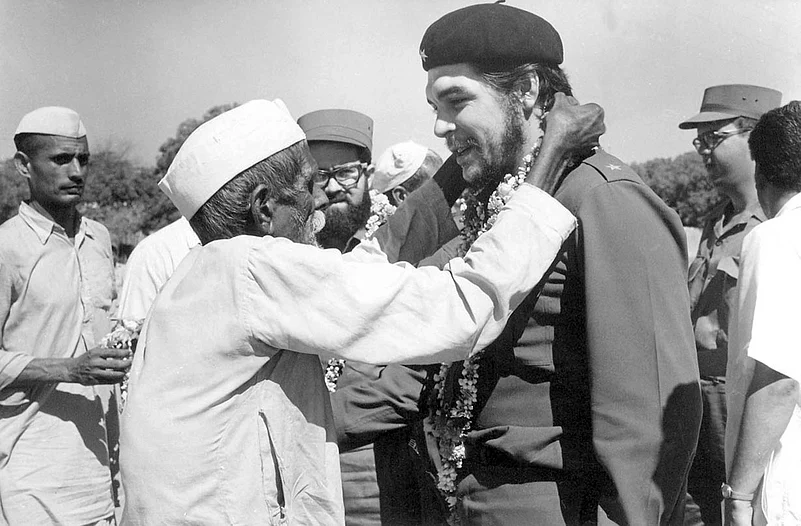

Yet these trials, intended to crush the nascent movement, instead, provided a platform for the propagation of Marxist ideas across the country. In the Meerut courtroom, Communists spiritedly explained and defended their ideology, transforming their prosecution into a seminar on revolutionary theory. The photograph of the 25 accused, taken outside the Meerut Jail, remains an iconic image: S. A. Dange, Muzaffar Ahmad, P. C. Joshi and other revolutionaries who would shape the movement for decades. At the first party congress, held in 1943, the 138 delegates present had been collectively served 414 years in colonial prisons. This single fact testifies the death defying patriotism and sacrifices made by the Communists for Indian independence.

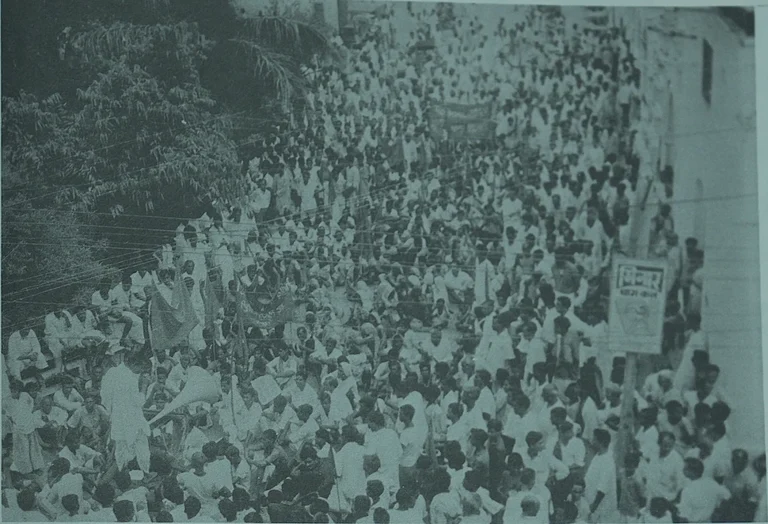

By the 1920s, Communists had established themselves as the most militant current within the anti-colonial movement. While the Congress often vacillated, Communists at the 1921 Ahmedabad session of the Indian National Congress moved a resolution demanding complete independence from the British rule, a demand that the Congress initially rejected. Along with the Workers and Peasants Party, the Communists organised industrial workers and peasants to form the All India Trade Union Congress and gather the All India Kisan Sabha into formidable mass organisations. In 1936, the All India Students’ Federation was founded, followed by the Progressive Writers’ Association and, in 1943, the Indian People’s Theatre Association. These organisations brought revolutionary consciousness to every section of Indian society. But it was the Telangana Armed Struggle of 1946-51 that demonstrated the revolutionary potential of Indian Communism most clearly. In the feudal hierarchical Nizam’s Hyderabad, where peasants were subjected to vetti (forced unpaid labour) and could be bought and sold, the Communists organised the most significant peasant movement since 1857. P. Sundarayya, who led the fight, documented the struggle in his monumental work titled ‘Telangana People’s Struggle and its Lessons’. Under the CPI’s leadership, the guerrillas armed with a few guns, lathis and slings and determination took on the Nizam’s forces and his Razakar militia. Women fought alongside men, shoulder to shoulder to defend their villages. At its peak, the rebellion established gram rajyams (village communes) across 4,000 villages controlling an area of 15,000 sq. miles with a population of four million. Approximately, one million acres were redistributed to landless peasants. The social transformation was revolutionary: caste distinctions were challenged, women’s participation in public life increased dramatically and feudal exactions were abolished. The rebellion led to 4,000 martyrs and more than 10,000 were imprisoned.

Similarly, the Punnapra-Vayalar uprising in Kerala in 1946 saw Communist-led workers and peasants challenge the autocratic rule of the Travancore princely state. The Tebhaga movement in Bengal demanded that sharecropper’s share be increased to two-thirds of the harvest. Crucially, this movement maintained Hindu-Muslim unity based on class struggle at a time when communal riots were raging in other parts of Bengal. The areas where the Kisan Sabha had influence remained free of communal violence. This was a powerful demonstration of class consciousness as an antidote to communal poison, a lesson that remains relevant today.

Democratic Achievements and Imperial Subversion

In April 1957, E. M. S. Namboodiripad took oath as Chief Minister of Kerala, leading the first democratically elected Communist government outside the Socialist Bloc. The ministry’s 28 months in power, before its dismissal in July 1959, laid the foundations that continue to shape Kerala’s exceptional social indicators. The Agrarian Relations Bill threatened feudal landlordism; the Education Bill challenged the stranglehold of caste and religious organisations over schools. These were not socialist measures, but democratic reforms that the Congress had promised during the freedom struggle, but never delivered.

The response was ferocious. The so-called ‘Liberation Struggle’ (Vimochana Samaram) united the Catholic Church, the Nair Service Society, the Muslim League, and the Congress Party in a campaign of organised disruption. What was long suspected is now confirmed by declassified intelligence files: the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the British MI5/MI6 mounted covert operations to bring down the Namboodiripad government. According to historian Paul M. McGarr’s recent research in the British archives, Congress leaders and union organisers were brought to the UK for intensive anti-Communist training. The CIA funnelled money to Congress politicians and anti-Communist trade unions. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who later became USA’s ambassador to India, confirmed American involvement in his 1978 book A Dangerous Place, noting the objective was to prevent ‘additional Keralas’. On July 31, 1959, President Rajendra Prasad invoked Article 356, establishing a precedent for the abuse of constitutional provisions against non-Congress governments that would be repeated for decades.

Yet, Kerala’s Communist legacy proved resilient. The Left Democratic Front has governed the state for much of its history, producing India’s highest literacy rates, best health indicators, strong labour protections and eradicating extreme poverty through its multidimensional approach. In West Bengal, the Left Front's 34-year rule (1977-2011), the longest uninterrupted tenure of any democratically-elected Communist government globally, achieved significant land reforms and decentralised governance through panchayati raj. The Communist contribution to India’s constitutional framework, though often overlooked, includes the emphasis on workers’ rights, land reform provisions, and the vision of social and economic justice enshrined in the Directive Principles.

The Present Crisis and Future Possibilities

The Communist movement today confronts some serious challenges. The Left has electorally faced some setbacks. India’s top one per cent now owns over 40 per cent of national wealth. Unemployment, particularly among the youth, has reached crisis proportions. The Narendra Modi government’s economic policies have accelerate workers while enriching a handful of oligarchs. The Hindutva movement, born in the same year as the CPI, has captured state power and is systematically dismantling the secular, democratic republic that Communists helped build. Muslims face lynch mobs, Christians face bulldozers, and Dalits face renewed caste violence, all under the protection of the State machinery.

Yet, history rarely moves in straight lines. As Communists themselves would note, contradictions intensify before they resolve. The very success of neo-liberalism and Hindutva is immiserating the masses and creating conditions for a renewed resistance. The farmers’ movement of 2020-2021, which forced the Modi government to retreat on its agricultural laws, demonstrated that mass mobilisation is possible. The international situation―with the decline of US hegemony and the rise of a more multipolar world order―has opened new possibilities for the Global South that were unimaginable during the Cold War.

The Communist movement’s centenary is a moment to look back at what they have achieved for the masses and the Indian state and to take inspiration from it for their future struggles. It calls for what Marxists term as a concrete analysis of concrete conditions. The fundamental questions that animated Indian Communists remain urgent: Who controls the land? Who owns the factories? Who makes the decisions that shape our collective lives? How do we build a society where, in Marx’s famous phrase, the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all?

A hundred years ago, young Indians inspired by the October Revolution and determined to end colonial rule chose the path of Communism. Many gave their lives for this choice. Whatever the electoral map shows today, their dream of a liberated India, free from exploitation, oppression, and the degradation of caste and communalism, remains unfulfilled. Perhaps this is the most important lesson of the centenary: the struggle continues.

(The author is a researcher and the Co-Coordinator of the Asia Desk at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

(Views expressed are personal)