“I claim, Sir, to come from a country, a part in India now, but which I think is of a different stock, not necessarily antagonistic. I belong to the Dravidian stock. I am proud to call myself a Dravidian. That does not mean I am against a Bengali, a Maharashtrian or a Gujarati. I say that I belong to the Dravidian stock and that is only because I consider that the Dravidians have got something concrete, something distinct, something different to offer to the nation at large. Therefore, it is that we want self-determination.”

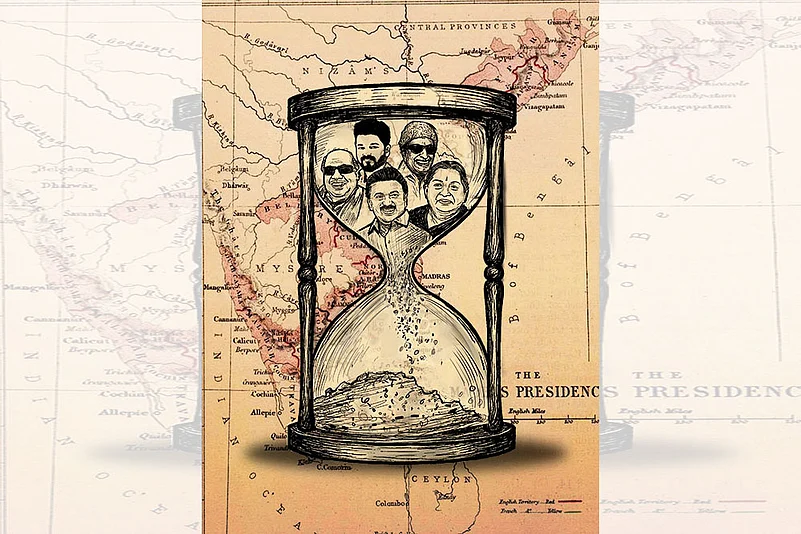

When C.N. Annadurai, the founder of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), delivered these words in his maiden Rajya Sabha address in 1962, he left members on both sides of the aisle spellbound. It was a speech steeped in sub-national consciousness, boldly challenging the mainstream narrative of Indian nationalism from the floor of the sovereign Indian Parliament. For many, it announced that a new political force that was rooted in Dravidian identity and Tamil pride had arrived with clarity and confidence.

Though the DMK later moved away from its early secessionist position, it has remained the country’s most vocal political force in demanding strict observance of federal principles. This continuity is evident in Chief Minister and DMK leader M.K. Stalin’s recent criticism of the Supreme Court’s opinion on prescribing timelines for Governors to act on bills submitted for assent. After the court declined to fix such a timeline, Stalin said he would not rest until a constitutional amendment made timely action mandatory. The stance reflects the DMK’s long-standing ideological line, consistent from its founding to the present.

The Dravidian movement emerged with a clear purpose: to challenge what it saw as the Union government’s growing drive to centralise power. For leaders like Annadurai, this was not merely a political disagreement but a question that touched the heart of Tamil identity, language and dignity. As the conflict between regional aspiration and federal centralisation intensified, the movement found deep resonance in Tamil Nadu.

By the time Annadurai stepped onto the political stage as a mass leader, this sentiment had become an electoral force. His articulation of regional pride, coupled with sharp critiques of the Centre’s policies, captured the public imagination in a way the Congress, long dominated by its stalwart leader K. Kamaraj, could no longer match.

The result was a dramatic realignment.

The Dravidian movement surged to power, riding a wave of popular enthusiasm, while Kamaraj’s once formidable Congress slipped to a distant second. In the years that followed, Congress gradually faded from the centre of Tamil Nadu’s political arena, leaving Dravidian parties to define and dominate the state’s narrative for decades.

Over the years, and more sharply under the present Prime Minister Narendra Modi-headed government, the Union government’s centralising impulse has grown significantly. Policies and instruments such as the National Eligibility cum Entrance Test (NEET), the New Education Policy and new mechanisms of central funding, as well as the threat of delimitation, have repeatedly been interpreted in Tamil Nadu as attempts to erode state autonomy. For the DMK government, this has meant occupying a position of near-constant resistance, confronting New Delhi on one front after another.

These confrontations have played out in different ways. At times, the fight has spilled onto the streets, as seen more recently during public outcry against the New Education Policy, when students, activists and political cadres turned the debate into a mass movement. At other moments, the conflict has shifted to the courts, with the state alleging that the Governor’s delays and interventions were carried out at the behest of the Union government. To the DMK, this reflects an increasingly centralised federal structure.

Meanwhile, Tamil Nadu’s political landscape has been undergoing its own churn. With the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) weakened by a prolonged leadership vacuum, the BJP has attempted to step into the role of principal opposition. The ideological contest is no longer merely administrative. It is a clash between the Dravidian political tradition, rooted in rationalism, social justice and regional pride, and the assertive Hindutva project the BJP seeks to advance.

The DMK is acutely aware of the shifting political terrain. Speaking to Outlook, Industries Minister and senior DMK leader Dr T.R.B. Raja admitted that the challenges before the party are real and evolving.

“There are forces attempting to change the very character of Tamil Nadu,” he says. “A divisive idea is being pushed consistently. But Tamil Nadu will resist it. By staying firmly anchored in constitutional values and pluralism, we can counter these attempts. We are also in constant communication with the people about the issues they face daily, despite the divisive tactics employed by certain forces. This approach resonates with people across demographic lines,” Raja added.

The BJP’s engagement with Tamil Nadu’s political spectrum has been long and strategic. Since the late 1990s, it has aligned with both major Dravidian parties, the DMK and the AIADMK, at different moments. Its cordial relationship with the DMK during the Vajpayee era, however, was short-lived and limited to a single electoral cycle.

The more consequential developments came after Jayalalithaa’s passing, when internal fissures began pulling the AIADMK in multiple directions. Sensing an opportunity, the BJP increased its involvement in the party’s internal affairs. According to veteran politician Panruti Ramachandran, an associate of the late MG Ramachandran and a minister in the latter’s, this shift may fundamentally reshape Tamil Nadu politics in the long run. “This is going to help the BJP,” he argues. “By aligning with the saffron party, the AIADMK has committed a cardinal mistake. It risks losing its core anti DMK voter base.”

In Tamil Nadu, 89 per cent of the population is Hindu, and within this, backward classes make up 45.5 per cent. Yet, Hindutva politics has struggled to gain a foothold here.

Ramachandran points out that neither MGR nor the AIADMK ever adhered to Dravidian ideology, or to any ideology in a strict sense. “MGR was immensely popular and felt he could lead a party of his own, so he formed the AIADMK. What concerns me now is the AIADMK’s proximity to the BJP at a time when the latter has grown into a formidable national force. Aligning with the BJP, especially when it has become such a behemoth, will only weaken the AIADMK further, inadvertently helping the BJP,” he warns.

The importance the BJP assigns to Tamil Nadu is evident in the many methods it has adopted to break its long-standing electoral jinx in the state. From organising the Tamil Kashi Sangamam to project a civilisational bond between Tamil traditions and the broader Hindu cultural landscape to presenting poet saint Thiruvalluvar in saffron, the BJP has repeatedly attempted to reframe Tamil icons within its ideological universe.

The most striking gesture was the installation of the sengol, a ceremonial sceptre from the Thiruvaduthurai Adheenam, inside the new Parliament building. Presented as a symbol of righteous governance rooted in ancient Hindu tradition, the sengol’s placement was widely interpreted as an attempt to weave Tamil religious heritage into the Hindutva narrative.

Political observers see these symbolic acts as efforts to co-opt elements of Dravidian cultural identity and fold them into the BJP’s national project. “It is a fact that the counter-culture narrative the DMK has been pushing for so many years has not been resonating with the younger generation as it used to do earlier. Though the DMK has identified this problem, it has to develop innovative methods. This, along with the weakening of the AIADMK, in the long run might help the BJP,” says Dr Arun Kumar, Professor, Political Science, Vellore Institute of Technology, Chennai.

While these cultural overtures unfolded subtly, Prime Minister Modi himself led the political push of Hindutva forces into Dravidian territory. A news report noted that since 2021, Modi has visited Tamil Nadu 18 times, most of them for political purposes. In the 2024 Lok Sabha election, although the BJP failed to win a single seat in the state, it increased its vote share significantly despite contesting without the support of either of the Dravidian majors. In 2019, the party contested only five seats. In 2014, it was in the fray in 19 constituencies. Its vote share rose from 3.59 per cent to 11.24 per cent.

A closer look at constituency-level data shows that the BJP’s rise has come predominantly at the AIADMK’s expense. In strongholds such as Coimbatore, Kanyakumari, Sivaganga, Thoothukudi and Ramanathapuram, the party has kept its vote share intact irrespective of alliances. In Coimbatore, where former BJP state president K. Annamalai contested and lost to the DMK’s candidate, the party retained the vote share it secured in 2019 when it was aligned with the AIADMK.

“The writing on the wall is clear,” Annamalai insists. “Eighty lakh people voted for the BJP in the last election. This is bound to double in the immediate future.” According to him, the party is gaining ground by offering representation to the underprivileged. Targeting the DMK, he says, “What the DMK passionately preached was never practised. That is why they could never win elections without alliances. The people of Tamil Nadu have started questioning the credibility of the DMK.”

Ahead of the 2024 Lok Sabha polls, Modi also invoked the 1998 Coimbatore bomb blasts that killed 58 people, paying homage to the victims. Investigators concluded that the February 14, 1998 explosions were part of a larger conspiracy, allegedly executed by Al Umma, an Islamist outfit formed after the demolition of the Babri Masjid, to assassinate senior BJP leader L.K. Advani. In the aftermath, Hindu communal groups attacked Muslim neighbourhoods and properties, sparking a major law and order crisis. Eighteen Muslims, some of them burnt alive, and two Hindus were killed in the retaliatory violence.

Although Coimbatore has not witnessed large-scale communal riots since then, fundamentalist organisations have kept tensions simmering. “The BJP is trying to divide people on communal lines and gain mileage out of it,” says Ganapathy Raju, the Coimbatore MP and former city mayor. “But our relentless campaign, especially among the youth and their commitment to pluralism, is standing as a bulwark against such penetration.” The DMK continues to foreground Dravidian values and warn against the dangers of what it says is the BJP’s strategy of communal polarisation. According to a district-level leader, CM M.K. Stalin has instructed his party to recapture the seats the BJP won in the 2021 Assembly election. That year, the BJP, contesting in alliance with the AIADMK, won four of the 20 seats it contested. A party functionary from Tirunelveli says Stalin urged them to focus on the seat held by state BJP president Nainar Nagendran.

“We are already the third largest party in the state,” says the BJP’s chief spokesperson, Narayan Thirupathi. “Under the guise of promoting Dravidian ideology, the DMK has been spreading a divisive ideology. People are realising this. There is no Aryan-Dravidian binary. Everything is Bharatiya. The DMK’s ideology is against this,” he says.

In Tamil Nadu, 89 per cent of the population is Hindu, and within this, backward classes make up 45.5 per cent. Yet, Hindutva politics has struggled to gain a foothold here. The reason lies in the deep-rooted cultural and political bulwark of Dravidianism. But as Hindutva ideology reshapes political narratives across much of the country, and as the state’s internal political dynamics shift, Tamil Nadu is emerging as a key battleground—one where culture does not merely influence politics but actively defines and contests it.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

N.K. Bhoopesh is an assistant editor, reporting on South India with a focus on politics, developmental challenges, and stories rooted in social justice