Summary of this article

The MGNREGA guaranteed not just employment, but dignity.

VB-GRAM) has ceased to be demand-driven—a change that fundamentally alters its character as a rights-based employment guarantee.

Under MGNREGA, the bargaining power of rural workers increased. VB-GRAM bans guaranteed employment for 60 days during peak farming operations. This will supply large landowners with cheap labour and is likely to push rural wages downward.

Kanjana’s working life traces the slow unravelling of Kerala’s rural economy over the last four to five decades. Born and raised in Ambalapuzha in Alappuzha district, she grew up as the daughter of a coolie worker and was compelled to contribute to the family’s income from a young age.

As a teenager, she entered the paddy fields. In those years, she found work across various stages of cultivation, earning enough to add her share to the household budget. But the employment was seasonal, and as paddy cultivation declined—squeezed by rising input costs and shrinking returns—many farmers abandoned crops altogether. Work came in short bursts, followed by long spells of uncertainty, forcing her to look elsewhere.

The coir industry, still a labour-intensive backbone of Kerala’s southern districts at the time, offered that alternative. Her days moved through the entire arc of production: dehusking coconuts, soaking the husks in backwaters, beating them into fibre, and finally cleaning, drying, and spinning the yarn. The work was repetitive and physically demanding, but it offered something crucial—continuity.

When the coir sector began to decline, undercut by mechanisation, shrinking state support, and a changing market, Kanjana—like thousands of others—was pushed into fish-processing units. There, the labour was harsher and the margins thinner. Long hours spent peeling prawns in refrigerated conditions took a toll on her health, eventually forcing her to abandon yet another occupation.

It was amid this instability, in her effort to keep body and soul together, that the thozhilurapp pandhathi—the Malayalam name for the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005, (MGNREGA)—emerged as a rare source of predictability. “It helped me face many weathers over the last several years,” she says, using a phrase that captures both climate and circumstance. The scheme did not promise prosperity, but it offered something more elemental: assured work close to home and the means to hold a family together. It also bridged the gaps between her stints in other sectors.

Kanjana is unaware of the technical changes and policy rehauls that have reshaped a programme on which lakhs of people like her depend. But she senses its weakening. “For some years now, there have been problems. I don’t know why. It is not as effective as it used to be,” she says. Her confusion mirrors a wider rural disquiet—where delays, restrictions, and shrinking workdays have quietly hollowed out a scheme that once functioned as a social safety net, absorbing the shocks of the rural economy’s uncertainties.

Kanjana, now in her 60s, still finds odd jobs and occasional MGNREGA work to support her family.

Anandavally’s story, however, is different. She lives with her son and daughter-in-law and does not depend on her wages for survival. “I used to go to work not out of necessity,” she says. “My son is employed and takes care of me. But this thozhilurapp scheme gives me prestige—the feeling that I live by earning. It gives me moral strength.”

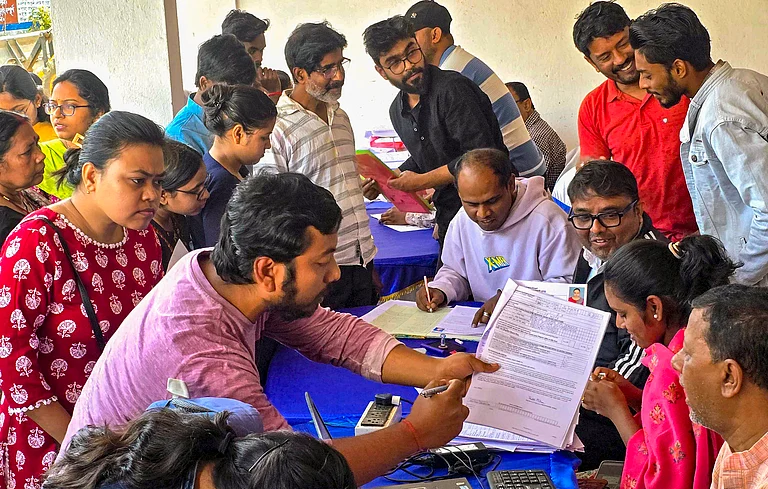

MGNREGA has meant different things to different people, as the lives of Kanjana and Anandavally illustrate. For some, it has become an essential and dependable source of livelihood. For others—a smaller minority—it offers a way to assert dignity and identity within the extended family. Yet for all of them, the scheme is not like charity but as a right: a rare, demand-driven programme that recognises work, autonomy, and self-worth.

“If we look at the age composition of women engaged in MGNREGA work, a large proportion falls in the sixty-plus category. Most of them had spent their earlier years in agricultural labour. But after sixty, many employers refuse to hire them, citing declining efficiency. The MGNREGA ensured that these women could work as long as they were able. It guaranteed them not just employment, but dignity,” says Aby George, former director, Social Audit, MGNREGA in Kerala.

According to experts, the most significant shift following the repeal of MGNREGA and the introduction of the Viksit Bharat-Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin) (VB-GRAM) is that, for all practical purposes, the programme has ceased to be demand-driven—a change that fundamentally alters its character as a rights-based employment guarantee. Section 4(5) of the proposed law states: “The Central government shall determine the State-wise normative allocation for each financial year based on objective parameters as may be prescribed by the Central government.” This provision, despite official claims to the contrary, effectively converts the scheme into a supply-driven programme, experts argue.

“There is a provision in the new law that also allows workers to demand employment from panchayat authorities,” says George. “But the irony is that the nature of the work and the location where it will be carried out are decided by the Central government. The stake of the panchayat at the crucial implementation level is minimal.” This provision makes the scheme highly centralised. The new law also stipulates an increase in guaranteed employment from 100 days to 125 days. But here, too, there is a rider that works against the states.

Under MGNREGA, rural distress results in higher fiscal outlays, with the Centre bearing the primary financial responsibility. Under the new regime, however, states are compelled either to finance the expansion of employment days from their own resources or to restrict access once the Centre’s allocation is exhausted. In effect, the risk of addressing rural distress is shifted downward—from the Union government to the states—diluting both the guarantee and the universality of the scheme. This is because, under the new act, the project has essentially become a centrally sponsored scheme, with the Centre bearing 60 per cent of the cost and the states the remaining 40 per cent. Under the MGNREGA, the state government bore only 25 per cent of the material cost. According to the VB-GRAM, “the fund-sharing pattern between the Union government and the State governments shall be 90:10 for the north-eastern states, Himalayan states/Union Territories (Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, and Jammu and Kashmir), and 60:40 for all other states and Union Territories with legislature.”

“When viewed through the prism of fiscal federalism, the repeal of MGNREGA and the enactment of VB-GRAM make political sense,” says Ramakumar of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences. “The intent behind the Narendra Modi government’s complete overhaul of the programme may not be immediately apparent, but it appears to be part of a larger effort to shift financial responsibility to the states.”

“As with most centrally sponsored schemes, the Union government will now fund only 60 per cent of the wage component and 40 per cent of the material cost, effectively pushing a greater share of the burden onto state governments,” he adds. “There were earlier reports that the 16th Finance Commission might recommend reducing the states’ share in the divisible pool of central taxes from the existing 41 per cent to 37 per cent. However, the fear of opposition appears to have prevented the Finance Commission from proceeding with this proposal. The Centre is now attempting to shore up its revenues by transferring fiscal responsibility in other ways, including through schemes such as VB-GRAM.”

The financial burden imposed by the new Act is evident. States such as Tamil Nadu and Kerala already allocate a substantial share of their revenue receipts—approximately 62 per cent and 69 per cent, respectively—to salaries, pensions, and interest payments. According to estimates, states would collectively have to spend approximately Rs 26,000 crore on wages alone under the new regime. For general-category states, the burden is significant: Tamil Nadu is estimated to incur an additional Rs 3,350 crore, while Kerala would need to find around Rs 1,500 crore.

Such additional fiscal pressure is likely to constrain state finances further and could adversely affect spending on the social sector, undermining welfare programmes that states have historically prioritised.

“If state governments are unable to mobilise their mandated 40 per cent share, the Union government may refuse to release its 60 per cent contribution,” says George. Experts warn that such a situation would inevitably trigger a political blame game between the Centre and the states, ultimately weakening—and potentially dismantling—the scheme itself.

Hostility towards MGNREGA is not new. When Modi came to power in 2014, the Prime Minister famously derided the programme, calling it a “living monument of the failures of previous Congress governments”. Speaking in Parliament in 2015, he said: “Sixty years after Independence, you still have to send people to dig holes. So I will celebrate this with pomp and splendour. I will tell the world that these holes you are digging are for your own sins.”

After the Modi government assumed office in 2014, MGNREGA employment fell by nearly 25 per cent in its first year.

Economist Jean Drèze has noted that the scheme has typically generated between 200 and 300 crore person-days of employment annually. Employment surged sharply during two major crises: in 2009-10 following the global financial crisis, and again between 2020 and 2022 during the COVID-19 pandemic. This pattern, Drèze argues, demonstrates the programme’s counter-cyclical nature. “During the COVID-19 crisis, MGNREGA provided critical fallback employment for unemployed workers and returning migrants,” he wrote.

Even the World Bank, which had initially dismissed MGNREGA as a “barrier to development” in its 2009 assessment, revised its position in 2014, describing the programme as a “stellar example of rural development”. Economists have also noted that MGNREGA has served as a buffer against distress-driven rural-to-urban migration.

Resistance to the scheme has historically come from sections of the farming sector. In 2011, Sharad Pawar, then a minister in the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) cabinet, proposed suspending MGNREGA for at least three months during peak agricultural seasons, arguing that it caused labour shortages during sowing and harvesting.

“In reality, after MGNREGA came into existence, the bargaining power of rural workers increased,” says Sudha Menon, a Gujarat-based researcher on labour and employment. “Large landowners who depended on cheap labour pressured the government to halt MGNREGA during the agricultural season to regain control over wages.”

According to her, MNREGA significantly strengthened the negotiating position of the rural poor. “VB-GRAM includes a provision to ban guaranteed employment for 60 days during peak farming operations. This will once again supply large landowners with cheap labour and is likely to push rural wages downward,” she warns.

The NREGA Sangharsh Morcha, a collective of MGNREGA workers, had earlier accused the government of presiding over a steady erosion of the scheme. According to the organisation, the average number of workdays provided per household declined to 44.62 days in 2024-25, down from 52.08 days in 2023-24. It also reported a sharp fall in person-days of employment—from 312.37 crore in 2023–24 to 239.67 crore in 2024-25. Person-days refer to the total number of days of employment generated for registered workers under MGNREGA in a financial year.

For several organisations and individuals associated with the employment guarantee programme, the writing has long been on the wall. They point to what they describe as the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government’s indifferent—and at times openly antagonistic—approach towards MGNREGA. The recent changes, they argue, amount not merely to reform but to a de facto repeal of the scheme as it has been known and experienced by millions of rural workers.