K. Annamalai’s removal as Tamil Nadu BJP chief in 2025 highlighted the continued influence of Dravidian ideology, as his attacks on iconic Dravidian leaders threatened the BJP’s prospects of rebuilding its alliance with the AIADMK.

His criticism revived historical debates, including the 1956 Madurai event where the Aryan–Dravidian divide resurfaced, and intensified tensions with the AIADMK, which still claims Dravidian ideological lineage.

The Hindutva camp, including Annamalai and Governor R.N. Ravi, has mounted strong ideological opposition to Dravidianism, setting the stage for a sharper ideological battle ahead of the 2026 Tamil Nadu elections

In 2025, Kuppusamy Annamalai, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) Tamil Nadu unit president, was compelled to relinquish his post for his relentless criticism of Dravidian political stalwarts. Coming exactly a century after Erode Venkata Ramasamy, better known as ‘Periyar’, launched the Self-Respect movement that laid the foundation of Dravidian politics, the development reflected the dominance that Dravidian political ideology still holds over the southern state.

The BJP’s Hindu identity politics is an ideological rival of radically secular and rationalist Dravidian identity politics. However, the widespread belief in political circles was that his party had to ‘sacrifice’ him for the sake of forging an alliance with the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK), the principal opposition of the state’s ruling Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) government.

In 2023, the regional party had walked out of the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA), blaming the BJP state leadership—Annamalai in particular—for “making unnecessary remarks about our former leaders for the past year”. After all, AIADMK may practise Dravidian politics in a much more diluted form than the DMK, but it still claims the legacy of Dravidian ideology. And Annamalai had targeted the late Dravidian ideologue, Conjeevaram Natarajan Annadurai, after whom the party is named.

The AIADMK’s snapping of ties in 2023 came shortly after Annamalai attacked a core AIADMK legacy, alleging that at a 1956 Madurai event, freedom fighter and Forward Bloc leader Muthuramalingam Thevar had sharply criticised Annadurai and PT Rajan for insulting Hindu gods during a temple speech.

Annamalai claimed that following Thevar’s bold criticism, “Annadurai was kept hidden in Madurai as he could not leave the town,” and later, “PT Rajan and Annadurai apologised and ran away from Madurai.” This aggressive criticism of CN Annadurai, the AIADMK’s guiding namesake, immediately threatened the alliance.

Annamalai’s September 11 remarks came following DMK youth wing chief and deputy chief minister Udhayanidhi Stalin’s September 2 call for the “eradication” of Sanatan Dharma, referring to a Brahmin-centric Vedic tradition. Dravidian politics has opposed Brahmin dominance since its inception. Annamalai had targeted Annadurai and PT Rajan, both of whom were Periyar’s followers and staunch atheists. But AIADMK was hurt no less than the DMK. With no evidence supporting Annamalai’s claims of Annadurai apologising, they quit the NDA when Annamalai refused to apologise and returned 19 months later only after the BJP removed him.

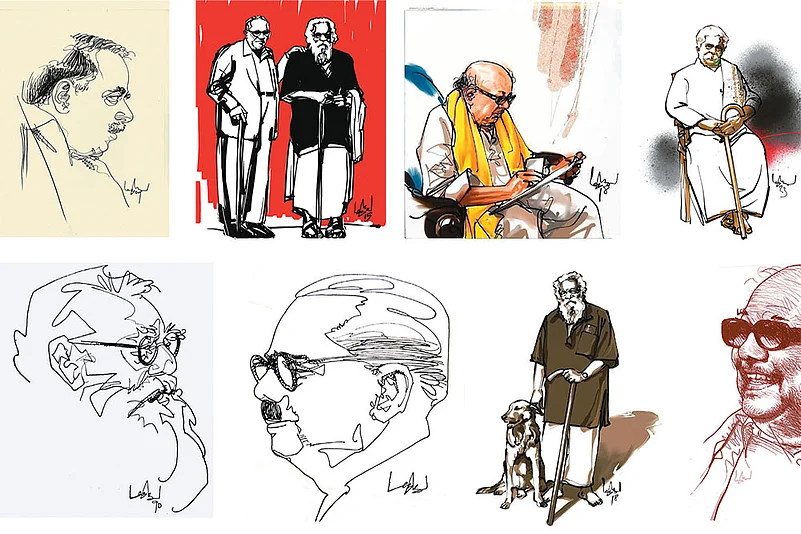

Dravidianism: The Journey

For over a century, Dravidianism has kept alive its fight against the Aryan supremacy ideals and politics of Hindu nationalist forces. It is a cultural conflict that has become part and parcel of the political arena. It also provided a different development model centred around social justice.

The seeds of Dravidian identity politics were sown in the 1810s rather unintentionally. In 1812, Francis White Ellis, a Madras-based East India Company servant, edited and printed The Thirukkural, the first text of Tamil Sangam literature to be published.

If this brought European attention towards India’s south for ancient excellence, non-Sanskritic and non-Vedic excellence to be precise, his 1816 essay identifying Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, Tulu, Kodagu and Malto as belonging to a different group of languages—as against the Indo-Aryan prevalent in India’s west, north and east—triggered a far greater curiosity.

Over the following decades, the Dravidian identity crystallised and subsequently paved the path for Dravidian identity politics—as opposed to the Aryan identity and Aryan supremacy-based politics. There were also three major developments.

German Indologist Franz Bopp’s book, A Comparative Grammar of the Sanskrit, Zend, Greek, Latin, Lithuanian, Gothic, German and Slavonic Languages, came out in 1845. It, too, affirmed Dravidian languages as belonging to a different group.

In 1847, in an essay titled On the Relation of the Bengali to the Arian and Aboriginal Languages of India, German Indologist Max Muller expanded the linguistic theory to argue that northern and southern languages were distinct and that their speakers belonged to different racial groups. He suggested that Sanskrit-speaking Aryans came from outside and subdued the original inhabitants of the subcontinent.

British missionary-turned-linguist Robert Caldwell reinforced this understanding with his 1856 publication, A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian or South-Indian Family of Languages, which also reproduced Francis Ellis’s 1816 essay. By then, a growing consensus held that Dravidian languages formed a separate linguistic group native to South Asia, unlike the Aryan languages believed to have spread from the Central Asian Steppes.

From the 1880s, the rediscovery and publication of Sangam-era Tamil works brought ancient Tamil literature, seen as being as old as Sanskrit if not older, into public attention. At the same time, early nationalists, especially the Annie Besant-led Theosophists, promoted pride in a Sanskrit-centric, Vedic Aryan heritage.

Against this backdrop, and fuelled by resentment against Brahmin domination in Tamil society, administration and politics, a non-Brahmin assertion based on a southern identity gathered strength. The Dravidian Association emerged in 1916 and, nine years later, Periyar, an atheist and fierce critic of Vedic and Brahmin authority, launched the Self-Respect Movement, laying the ideological foundation for organised Dravidian politics.

They equated Vedic civilisation with caste-based discrimination and oppression and argued that Aryan immigrants had introduced the caste system in Indian society to subjugate the original inhabitants of the land.

Dravidianism is facing a new challenge from an old rival–Hindu nationalism—in a far more powerful avatar.

However, Dravidianism lost some of its appeal at the time of Independence when the demand for a separate Dravida Nadu, comprising the southern states, failed to win support among Telugu or Kannada-speaking people or among Malayalis. Many feared Tamil domination in such a federal structure. Though anti-Brahminic in its very nature, the movement also struggled to align fully with the Dalit movement, since Dravidian politics continued to be led largely by intermediary and middle castes. Despite this, Dravidian assertions against perceived Vedic Aryan supremacy continue to shape politics in Karnataka and, to a lesser extent, Kerala, particularly in the linguistic and cultural domain.

Archival records show the Aryan-Dravidian debate coming alive during the 1956 event in Madurai—the one that Annamali had referred to. During its inauguration, senior Congress leader Chakravarti Rajagopalachari, India’s last governor-general and a former chief minister of erstwhile Madras, urged the audience to promote Tamil literature while “eschewing caste and communal differences”. Rajagopalachari described it as “unfortunate that a set of people, calling themselves Dravidians, developed ill feelings against the so-called Aryans.” Such a sentiment, he argued, was “meaningless and should be rooted out.” He warned against converting Tamil into a tool to “raise communal feelings.”

Other speakers sharply criticised his remarks during the remaining days of the golden jubilee celebrations of the Madurai Tamil Sangam, which were organised by PT Rajan, then a prominent DMK leader. Within a decade, Dravidian politics established itself as the dominant ideological force in Tamil Nadu, boosted by mass mobilisations against Hindi imposition.

The Congress suffered a decisive defeat in the 1967 election and Annadurai became the first Dravidian chief minister. Since then, power in the state has alternated only between the two Dravidian parties, while the Congress abandoned its earlier ideological confrontation. But after Narendra Modi became prime minister in 2014, the Hindutva camp signalled a direct ideological challenge to Dravidianism, setting the stage for a renewed confrontation in Tamil Nadu’s politics.

The Conflict Intensifies

Annamalai’s removal and the AIADMK’s return to the NDA fold did not stop the Hindutva camp from targeting Annadurai. In June, the Hindu Munnani (Hindu Front), a Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh-backed organisation, hosted the Murugan Bakthargal Aanmeega Maanadu (Murugan Devotees’ Spiritual Conference) in Madurai with support from the BJP. During the event, a video clip allegedly portraying Periyar, Annadurai and Karunanidhi in a poor light sparked fresh controversy. In the clip they were referred to as “atheist foxes”.

While the DMK sharply criticised the Hindutva camp, the AIADMK response was noticeably muted. This encouraged the DMK to escalate its attack on the AIADMK, arguing that the party had forfeited the right to carry Annadurai’s name. The Tamil Nadu BJP, however, did not yield despite its ally coming under pressure. Instead, it defended the video, describing it as a critique of atheism.

Following the controversy, CPI(ML)(Liberation) leader Balasundaram wrote in the party’s mouthpiece, Liberation, that Murugan was being used as a shield by Hindutva forces against Dravidianism. “They adopt a metaphor of Murugan as Hindutva and asuras (demons) as Dravidianism. This must be tirelessly countered at (the) ideological and political level,” he asserted.

Annamalai has not been the only prominent face of the Hindutva camp’s ideological campaign in Tamil Nadu. Governor RN Ravi has often taken a direct stance against Dravidian politics. In March 2024, he described Robert Caldwell’s 1856 publication, Comparative Grammar of Dravidian Languages, as “a fake book” and a colonial conspiracy to divide India on north-south lines. He accused Dravidian politics of being allegedly “separatist” and “racist”, challenging the foundational arguments of the movement.

The DMK, in turn, has continued to intensify its ideological counter-offensive. In January 2025, Chief Minister MK Stalin announced a one million dollar prize for successfully deciphering the Indus Valley script, expressing confidence that it would prove the civilisation’s ties to Dravidian culture and reinforce the argument of Dravidian primacy over the Vedic order.

In June, Stalin alleged that the BJP-led Union government was deliberately withholding reports related to the excavations in Keezhadi, an archaeological site in Tamil Nadu that has revealed evidence of a sophisticated non-Vedic urban civilisation potentially dating back to the sixth century BCE. This withholding, Stalin argued, reflected the BJP’s “hatred for Tamil pride”. “The BJP wanted to destroy the symbol of Dravidian culture by promoting the fictional Saraswati civilisation (in the north), which lacked credible evidence, while dismissing the proven antiquity of Tamil culture,” he alleged.

Notably, the Hindutva camp has long sought to project the Indus Valley Civilisation as a Vedic one and has popularised the term “Saraswati civilisation”, despite the Harappan civilisation widely being regarded as pre-Vedic.

A century after the Self-Respect movement, Dravidianism remains one of the fiercest critics of the Vedic Aryan identity politics of Hindu nationalists, from rejecting northern claims of Sanskritised civilisational superiority and challenging Brahmin dominance of Aryan culture to opposing the imposition of Hindi, a northern language. Recently, Udhayanidhi reiterated that Sanskrit is a dead language.

However, Dravidianism is also facing a new challenge from an old rival–Hindu nationalism—in a far more powerful avatar. As the 2026 elections approach, it remains to be seen whether the Hindutva camp focuses on criticising the DMK over corruption, dynasty politics and an alleged anti-Hindu stance or continues to target the Dravidian ideology itself.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Snigdhendu Bhattacharya is a journalist, author and researcher