Summary of this article

Vande Mataram was composed in 1875 and included in the controversial 1882 novel, Ananda Math

The song gained immense popularity among freedom fighters from the beginning of the 1900s

After the emergence of Muslim League, there was growing objection to the song’s polytheism and anti-Muslim context

Since the Bihar assembly election campaign began in early November, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has been targeting the Congress, India’s key opposition party, for allegedly paving the path to India’s Partition by adopting a truncated version of the Vande Mataram hymn as India’s national song.

The Congress took the decision in 1937, a decade before Independence that came with the Partition.

Bengali novelist Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, who Union Home Minister Amit Shah had earlier described as the “fountainhead” of their brand of Hindu ‘cultural nationalism’, had composed Vande Mataram as a six-stanza poem, originally published in 1875. He later included it in his 1882 novel, Ananda Math.

In 1937, amidst raging controversy around the song, the Congress—then India’s chief platform for the national liberation movement, adopted only the first two stanzas of the song as India’s national anthem.

How the contention resurfaced

The sudden revival of this decades-old episode came around the government-backed year-long commemoration of Vande Mataram to celebrate its 150th anniversary.

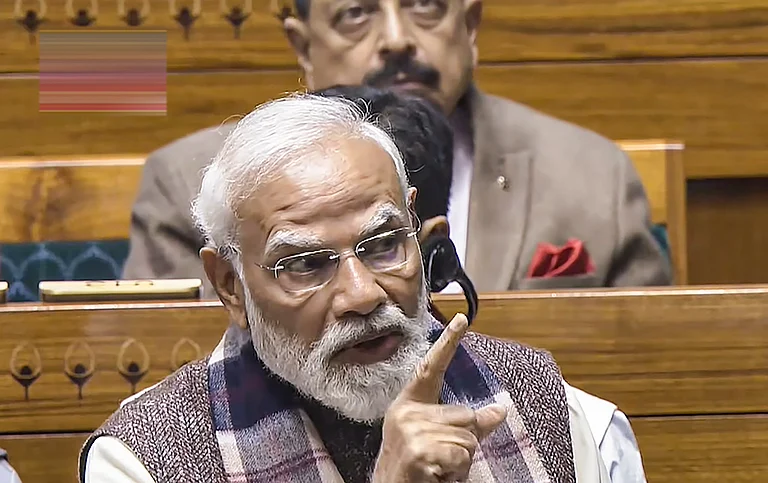

In the first week of November, Prime Minister Narendra Modi alleged that the dropping of “crucial verses of Vande Mataram” meant the severing of a part of its soul which “also sowed the seeds of division of the country.” According to Modi, the matter remains relevant because “that same divisive thinking remains a challenge for the country even today. The Congress must answer for the “injustice done” to the “great mantra of nation building,” he had said.

Upping the ante, the Modi government raised the issue during the special discussion held in the Parliament on December 8 to celebrate the song’s 150th anniversary. Modi blasted former Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru—who headed the Congress in 1937—for fragmenting the song “by bowing to the Muslim League.” The Congress compromised on Vande Mataram, “the mantra of India’s freedom struggle,” Modi alleged.

Amid the debate on Vande Mataram in Parliament, Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind chief Maulana Arshad Madani said that Muslims had valid reasons to object to that song, particularly four verses where the homeland is explicitly likened to a deity and words of worship are used for it.

“We have no objection to anyone reading or singing Vande Mataram. However, we want to make it clear once again that a Muslim worships only one God, and cannot associate anyone else with this worship,” Madani said in a statement.

“The meaning of ‘Vande Mataram’ is essentially ‘Mother, I worship you,’ which goes against the religious beliefs of a Muslim,” Madani said, adding, “No one can be forced to chant or sing any slogan or song that contradicts their faith.”

In Tagore, the middle path

This almost looks like a rerun of the original Vande Mataram controversy nearly nine decades ago. In 1937, the Congress was sharply divided on the question of singing Vande Mataram at the Congress session in Kolkata. Many Hindu leaders wanted it, but many Muslims objected.

The polytheistic nature of the song—it includes an ode to goddess Durga—is only one of the reasons for objection. Another key reason was the context in which the song was used in the Ananda Math novel. The novel pits Hindus against Muslims—and not the British colonial power.

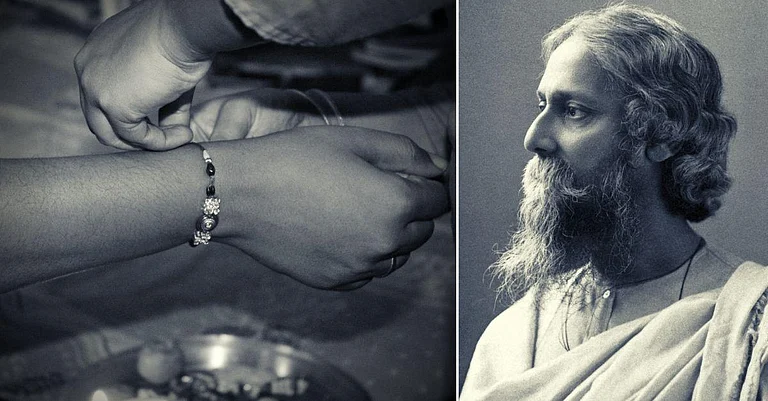

When the Congress’ Hindu leadership, especially those in Bengal, was bent on having the whole song performed on the dais during the Kolkata session, and Muslims were equally rigid not to sing it, Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose approached the Nobel laureate polymath Rabindranath Tagore for his opinion.

It was Tagore who first set the song to tune, sung it before Chattopadhyay and performed at a Congress event in Kolkata in 1896—well before the song attained the stature it did.

Tagore wrote to Nehru, saying that, to him, the spirit of tenderness and devotion expressed in its first portion (first two stanzas) and the emphasis it gave to beautiful and beneficent aspects of our motherland appealed so much that he found no difficulty in dissociating it from the rest of the poem and from the novel.

Pluralism at the core

Except for the high quality of the first two stanzas, he would not have had any sympathy or sentiment for the text, as he had been brought up in the monotheistic Brahmo ideals. Allaying concerns of the Muslims, he said that he freely concedes that the whole of the poem, read together with its context, “is liable to be interpreted in ways that might wound Moslem susceptibilities.” However, the first two stanzas need not remind us every time of the whole of it, much less of the story (Ananda Math) with which it was accidentally associated. The first two stanzas “acquired a separate individuality and an inspiring significance of its own in which I see nothing to offend any sect or community,” Tagore opined. It’s based on his opinion that the Congress arrived at the compromise formula—the middle-path: adopting only the first two stanzas as the national song. Following this, Tagore himself faced backlash from the Bengali Hindu society, many of whom thought the Muslim sensibilities were unjust. However, as author and journalist Semanti Ghosh pointed out in a recent article in the Bengali daily Anandabazar Patrika, Tagore defended his choice in a letter to litterateur Buddhadeva Bose. Tagore argued that the national anthem of India should be a song in which not only Hindus, but also Muslims, Christians, and even Brahmos can participate with respect and devotion. “Do you mean to say that Muslims must accept, in a national song, the hymns praising Hindu goddesses such as ‘Tvam Hi Durga’, ‘Kamala Kamaladalaviharini’, ‘Vani Vidyadayini’, ‘whose idols are worshipped in temples’, etc?” Tagore had asked Bose. It’s Tagore’s pluralistic middle path that has now come under the Hindutva hammer.