Summary of this article

Rahman has returned after 17 years in exile

Since August 2024, rise of Islamist forces is palpable

Progressives and liberals perceive him as a saviour

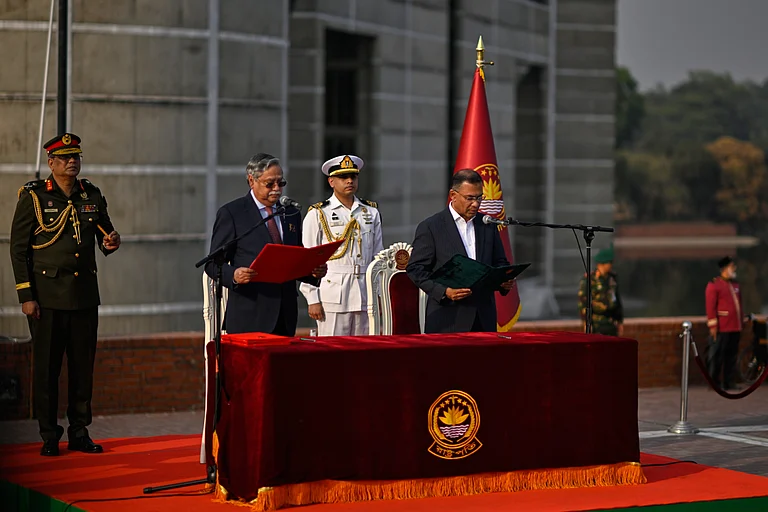

Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) helmsman Tarique Rahman returned to Bangladesh on December 25, 2025, after over 17 years of exiled life—6,314 days, precisely. Quite expectedly, emotions overflowed over his landing and public reception.

As the acting chairperson of the BNP, the largest party in the country since the ouster of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s Awami League (AL) government in a mass uprising in July-August 2024, all eyes are on him. Tens of thousands gathered to catch a glimpse of the 60-year-old whom many are seeing as a prime minister-in-waiting.

However, the timing of his arrival could not have been trickier. Hasina’s authoritarian rule has been replaced by mobocracy under Chief Advisor Muhammad Yunus’s interim government. A rule of lawlessness is weighing heavily on the people and economy. Bangladesh is desperately looking for restoration of democracy, but right wing Islamist forces are trying to convert the nation into an Islamic theocracy.

At the same time, the rise of right wing Islamist forces has forced many, especially the progressive and liberal sections of the society, the urban middle class and the rising middle class of the suburbs, to desperately find a saviour in Rahman. The BNP being a centrist force branding itself as liberal, these people need Rahman more desperately than one could ever imagine.

However, many conspiracies are reportedly being hatched—including by terror groups and Islamist fanatics who regrouped using the post-Hasina political vacuum and administrative paralysis—to thwart the elections scheduled in coming February, in which BNP is being widely seen as the favourite.

Rahman arrived, burdened with immense expectations and complex challenges. He tried his best to boost the confidence and morale of his support base.

“We want peace in this country,” Rahman repeated thrice as he addressed a mass gathering organised for his public reception. The audience roared. “It’s time to build the country together. This country belongs to the hills and the plains, the Muslims, Hindus and Christians. We want to build a safe Bangladesh where a woman, man or be it a child can safely move out of home and return.”

He stressed that regardless of one’s religion, social class and political affiliation or beliefs, everyone must ensure, at all costs, that peace and order is maintained. Safety of all—people of all ages, gender, classes, professions, and religions—should be the country’s aspiration today, he said. “We must reject any form of disorder at all costs and ensure that people can live in safety.”

These statements are expected to resonate with many. During the 17 months of the Muhammad Yunus-led interim government, the country has witnessed how mobs mobilised by Islamist forces and influencers are literally holding the government to ransom—targetting people or establishments at their will. The absence of law enforcers in almost all events of mob attacks has left people deeply anxious.

Building on legacy

The kind of uncertainty Bangladesh is living through is quite similar to that of the time when Tarique’s father, General Ziaur Rahman, took over the country’s presidency. Following the assassination of President Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and most of his family members by some mid-ranking army men in August 1975, Bangladesh saw back-to-back coups on November 3 and November 7, 1975—throwing the country into utmost uncertainty.

Zia, a hero of Bangladesh Liberation War, emerged in governance at this hour—first as a military ruler and then as head of a civilian government formed by the BNP, the party he launched in 1980. Tarique has Zia’s legacy to depend on.

During the late 1970s, Zia tried to steer the country from martial law to civilian rule by opening the doors for multi-party democracy and media freedom and pursuing rather unpopular policies like population control and mass literacy campaigns.

Zia allowed Jamaat-e-Islami (JeI), the pro-Pakistan force that opposed Bangladesh Liberation War and colluded with the Pakistani army in committing war crimes on liberation fighters in the then East Pakistan, to return to politics. However, he also strictly ensured Islamist fanaticism found no space. Zia reportedly survived 21 attempted coups and assassination attempts, eventually succumbing to the 22nd attempt on 30 May 1981. This led the country to another decade of military rule.

Zia’s wife, Begum Khaleda Zia, who took the reins of the BNP after his assassination, led the BNP to a victory in the country’s first free and fair election held in 1991. Since then, the JeI remained in alliance with the BNP for most part until 2022.

A chequered past

Tareque, apart from the legacy of his parents, also has the burden of memories of many allegations of misrule during the last BNP-JeI government (2001-06) led by Khaleda Zia.

The post-uprising scenario has turned the BNP and the JeI into bitter rivals. The JeI emerged as a formidable force, with its student wing, the Islami Chhatra Shibir, sweeping elections in major varsity campuses. As journalist Nazmul Ahasan described in a Facebook post, the country is seeing “the strongest pro-Jamaat sentiment we have seen in a lifetime.”

However, the increasing intensity of mob attacks have also left many people deeply anxious, desperately looking for someone to bring stability.

Fahmidul Haq, a Bangladeshi academic based in the US, sees Rahman as a transformed politician. Haq argues that during his 17 years in London, Rahman has internalised European liberalism. “His regal return is taking place at a time when Bangladesh’s politics truly needs him. In fact, it would have been even better had his return happened earlier,” says Haq.

Rahman tried his best to appear grounded. Rahman, wife Zubaida and daughter Zaima came on a commercial flight—not a chartered one—carrying their pet cat, Jebu, along. After landing, Rahman took off his shoes and socks to touch the soil of Bangladesh barefoot. He looked thrilled. The atmosphere was electric.

The mass gathering that the BNP organised for his public reception was held at a place in the outskirts of Dhaka, the national capital—as opposed to a central location—to spare the people the nightmare of traffic jams. There was a grand chair for him on the dais, but he refused it and got a simple chair for himself.

Rahman had left the country when it was going through another period of turmoil. The BNP-JeI government of Prime Minister Khaleda Zia had completed its 5-year term in October 2006, following which a caretaker government took charge. However, another military-backed caretaker government emerged in January 2007 and it launched a crackdown on the major politicians of the two major parties, the BNP and the AL.

Tarique was arrested in March 2007–six months before Khaleda’s arrest—and was quite evidently tortured in custody. He was granted bail on September 4, 2008, a week before his mother got bail. He left the country for the UK for treatment, along with wife and daughter, the very day Khaleda Zia came out of jail.

After the return of the Hasina government through the December 2008 election, a series of cases slapped on Rahman made it almost impossible for him to return. After Hasina’s fall in August 2024, Rahman was acquitted in all the cases in which he had been convicted during Hasina’s rule.

According to Mubashar Hasan, a Sydney-based Bangladeshi academic who survived a case of forced disappearance during the Hasina regime, Rahman's return also has significance for the 'personal', apart from the political.

He pointed out that Rahman faced custodial torture and was forced into exile. His political activities were curbed and there was a ban on the media in publishing his statements. This model was first applied to him and then extended to anyone the government felt threatened by.

“From that perspective, his return symbolises the reclamation of both political and personal agencies,” Hasan tells Outlook. “Politics is not without personal premises and, therefore, Rahman's return has a psychological significance."

Hasan adds that his return is expected to largely fill the political vacuum that right wing and far right forces have been using for so long to destabilise the country.

Rahman landed in Bangladesh amidst a strong and concerted effort by Islamist forces to distort and destroy the history of the national liberation movement and the Liberation War of 1971, and to even renounce the national liberation struggle because it was based on Bengali linguistic identity of the populace as against the religious identity of the Muslim-majority land.

But Rahman held the achievements of 1971 high. “The people of this land achieved freedom in 1971. In 2024, people from all sections of the society came together to protect our freedom and sovereignty. Today, the people of the land want to get back their right to free speech and democracy.”

After all, this party was founded by a liberation war veteran, the man who first announced Independence from Pakistan in a radio statement in the aftermath of Mujibur Rahman’s arrest in March 1975.

In 1981, following Zia’s assassination, the New York Times described him as a “strict leader who tried to give the nation direction.” Now, many in Bangladesh are looking at Tarique to play that role—to give the nation direction. “I have a plan,” Rahman said on the day he landed in his homeland, without revealing much of it.

People in Bangladesh and political observers abroad will keenly watch out for him to make his next moves as the election date inches forth.