Summary of this article

PM Modi linked the 1937 Congress compromise on Vande Mataram to long-standing political controversies.

He highlighted Nehru’s 1937 letter to Subhash Chandra Bose after Jinnah opposed the song.

Modi noted the 100-year anniversary of Vande Mataram coincided with the Emergency, framing it as a period of national constraint.

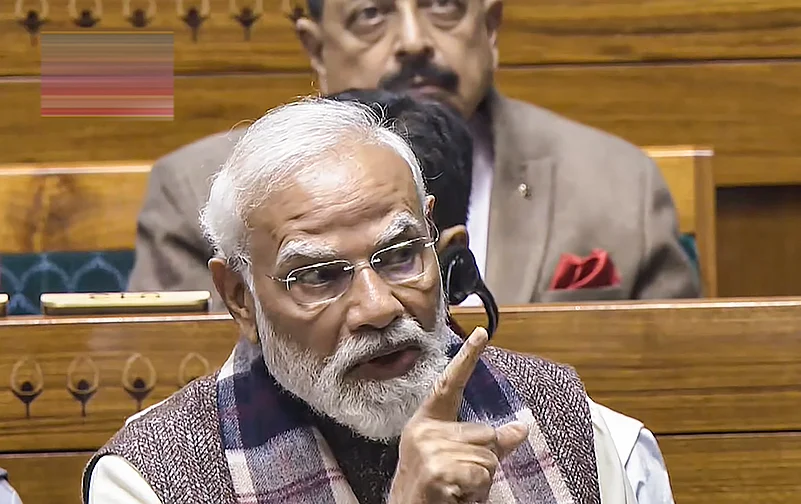

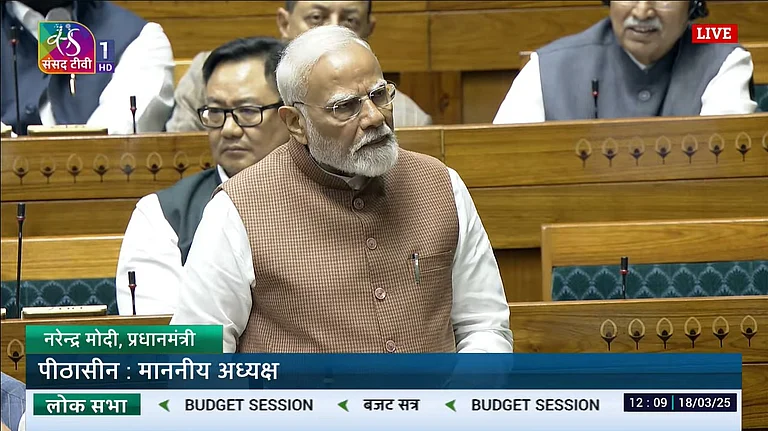

Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Monday linked the controversies over India’s national song, Vande Mataram, to Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru’s political decisions and the country’s experience during the Emergency. He criticised Nehru for accepting the view that the song might alienate Muslims.

Addressing the Lok Sabha during a day-long discussion marking 150 years of Vande Mataram, Modi said the song’s history reflects both political compromise and the nation’s struggle with authority. He alleged that Nehru had followed Muhammad Ali Jinnah in opposing Vande Mataram on the grounds that it could “antagonise Muslims”.

“When Vande Mataram marked its centenary, the country was caught in the Emergency… when it marked its 100th year, the Constitution was throttled,” he said.

“Congress compromised on Vande Mataram and, as a result, had to accept the decision of the country’s partition,” Modi said. “Congress’ policies have remained the same, and after years, the INC has now become the ‘MMC’. Even today, Congress and those carrying its name try to create confusion over Vande Mataram.”

Tracing the roots of the controversy to the pre-independence period, Modi cited a letter Pandit Nehru wrote to Subhash Chandra Bose after Mohammad Ali Jinnah opposed the song. In it, Nehru acknowledged he had read the background of Vande Mataram and thought it “might provoke and irritate Muslims.” He added that the Congress would examine the song’s use, particularly in Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s Bengal.

Modi noted that the Muslim League’s opposition to Vande Mataram had intensified in 1937, with Jinnah raising slogans against the song. Instead of condemning these statements, Modi said, Nehru began “investigating” Vande Mataram merely five days after Jinnah’s opposition, failing to express his own or the party’s loyalty to the song.

Highlighting the broader historical context, the Prime Minister drew attention to the song’s anniversaries. “When Vande Mataram completed 50 years, the country was under colonial rule. When it completed 100 years, the Constitution was throttled, and the nation chained by the Emergency,” he said, linking the song’s journey to India’s enduring struggles with authority and compromise.

PM Modi also invoked Mahatma Gandhi, noting that in the December 2, 1905, edition of Indian Opinion, Gandhi wrote that Bankim Chandra’s Vande Mataram had become widely celebrated in Bengal and was so beloved it felt like a national anthem, carrying deeper emotion and greater melody than many other national songs.

“Vande Mataram was written at a time when, after the 1857 uprising, the British government was alarmed and imposing new forms of repression. There was also a drive to push the British anthem, God Save the Queen, into every household.

Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay answered this challenge with Vande Mataram, written with firm resolve. When the British partitioned Bengal in 1905, the song became a unifying force,” he said.

Modi then questioned why the song had faced “injustice” over the past century. “If Vande Mataram was so revered, why was it sidelined? Which forces allowed their preferences to outweigh Gandhi’s sentiments?” he asked, arguing that Congress’s compromises contributed to the circumstances that ultimately led to Partition.

The discussion in the Lok Sabha, expected to last ten hours, commemorated 150 years of Vande Mataram, examining its cultural significance and political history. Modi framed the song not just as a national anthem but as a reflection of India’s trials, from colonial oppression to internal political disputes, and from Nehru’s compromises to the constraints of the Emergency.