Summary of this article

Pracha accuses the CBI and state authorities of failing the survivor while protecting the convict.

He highlights the societal implications, warning that the verdict may embolden perpetrators of sexual violence.

Known for his high-profile and controversial legal battles, Pracha continues to challenge powerful institutions and judicial decisions.

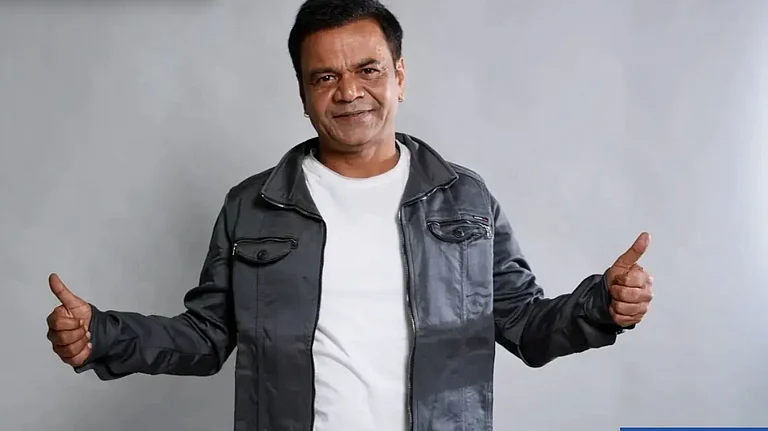

The corridor outside advocate Mehmood Pracha’s office is abuzz with restless energy. Junior lawyers and interns hurry back and forth. They are clutching stacks of files. Phones pressed to ears, voices low but urgent.

From the walls, portraits of Dr B.R. Ambedkar, the architect of India’s Constitution, seem to watch over Pracha’s work, a reminder of the ideals he strives to uphold.

The office of the rights lawyer is crowded, chaotic, intense. A physical manifestation of the battles he has been waging over years. And often against the powerful and established institutions.

Pracha is an unconventional lawyer, at a time when many may shy away from confrontation with the state, he appears to embrace it. His reputation is defined not just by the cases he takes. It’s also defined by the defiant tenor with which he puts across his arguments, whether in court, on the street, or in media interviews.

The air is thick with disbelief over the Delhi High Court’s decision to suspend the life sentence of convicted former BJP MLA Kuldeep Singh Sengar in the 2017 Unnao rape case and grant him bail, a development that has set off waves of national outrage and reignited debates about justice for survivors of sexual violence. Pracha speaks to Outlook, outlining what he sees as the chilling societal consequences of the verdict.

“Justice Has Become the Victim”

Pracha, a lawyer deeply enmeshed in India’s most contentious legal and political fights, when asked where the Unnao case stands today, his voice tightened. “This case stands in a dire state,” he says. “There are certain cases like Asifa’s case, the Hathras case, and now Unnao that shakes the conscience of the entire society. But in India today, judicial delay has become so normal that justice itself becomes the victim.”

Criticising the judiciary’s own explanations for delay that courts are overburdened, and don’t have enough time for each matter, he says, “If these systemic cracks are treated as normal, then what purpose does a Ministry of Justice serve at all?”

He described the High Court’s decision as an “extraordinary act of mercy to the convict”, one he sees as neither equitable nor legally justified. “This judgment sends a terrifying message,” he said. “Every paedophile, child molester, child rapist, every murderer of women and children will now feel confident. They will argue that if Kuldeep Singh Sengar, after everything he’s done, deserves such magnanimity and mercy from a premier High Court, then every other offender deserves the same.”

He imagines the chilling logic that might now come from future defendants: “I only raped one girl; I didn’t kill anyone; I didn’t attempt murder repeatedly… so I should get bail.” Pracha warns that even the worst undertrials might begin to get bail “without serious argument”, a development he calls “horrific.” His voice rising as he leans forward, “This is not legal reasoning. This is moral abdication.”

The CBI, the State, and the System Against the Survivor

Pracha does not stop at the judiciary. He points an accusing finger at the CBI and government machinery. “My opinion is that the CBI is 100 per cent complicit,” he says. “Central government officials involved in this case are complicit with Sengar. The UP government is complicit.” He describes “network, a cartel, gangs who are friends of Kuldeep Singh Sengar”, a description aimed at the broader sociopolitical influence he believes has shielded the accused.

He alleges that in similar cases, individuals connected to powerful networks have walked free “with flying colours” while victims were labelled liars and abused further.

Pracha again accuses the CBI of failing the survivor: “One ground of the suspension order,” he notes, “was that the girl did not say ‘X’ during the trial and that the CBI did not protest strongly.” In his view, even the judge “found” that the investigating agency at that time had helped the accused. And now, he adds, even after conviction, the CBI, along with state governments, continues to “help the convict” while the survivor struggles alone against “insurmountable odds.”

Open Court and Public Scrutiny

For Pracha, the fight isn’t just legal, it’s civic. He talks about how Dr. B.R. Ambedkar envisioned an open court system where the public could witness justice being done and hold it accountable.

“People must see what is happening,” he insists. “They should comment, criticise or appreciate judgments.” Then, with unflinching directness, he addresses common fears about protest: “Many people tell me, if we protest peacefully, the police will beat us, arrest us, implicate us.” Yet, he says, the choice is with the people of India. Speak out or remain silent. “If you want to keep your daughters, children, granddaughters, sisters, wives, even mothers safe, you must criticise this judgment or appreciate it. The choice is yours.”

A Lawyer Who Refuses to Play Safe

Pracha’s activism extends far beyond the Unnao case, and his methods have often placed him at the centre controversy. He has represented several accused in the 2020 Northeast Delhi riots cases. In December 2020, his Delhi office was searched for nearly 15 hours by the Delhi Police Special Cell. The action was criticised by the Bar Association of India, the Supreme Court Bar Association, the Bar Council of Delhi, and several senior jurists, who termed it a violation of attorney–client privilege and an attempt to intimidate a practising lawyer.

In a 2023 order relating to one of the riots cases, a Delhi court rebuked Pracha for making what it described as “wild and unsubstantiated” accusations against the special public prosecutor.

An Ambedkarite lawyer and activist, and National Convenor of Mission Save Constitution, Pracha doesn’t shy away from taking combative legal and political positions. He has been sharply critical of the Supreme Court’s historic Ayodhya Babri Masjid–Ram Janmabhoomi judgment, alleging bias in the judicial process and questioning institutional integrity. His petition challenging the verdict was dismissed in 2025, with the court imposing a ₹6-lakh penalty and terming the plea an abuse of judicial process.