Summary of this article

The spy film genre has evolved over decades in the Bollywood film industry.

People have enjoyed watching spy films for their technical finesse, moral ambiguity and edge-of-the-seat action.

Over the years, spy films have witnessed a steady change in their approach and audience response. This article aims to shed light on the same.

Spy films have always promised a particular kind of devious pleasure, drawing audiences into secretive worlds governed by clever minds, high stakes and moral compromises. For decades, Hindi cinema understood this rhythm instinctively. The spy was never merely a man with a gun—he was a figure navigating uncertainty, burdened by ethical weight, operating within a murky system. The early espionage and spy-adjacent films like C.I.D. (1956), Aankhen (1968) or even Drohi (1992) relied less on overt muscularity and more on moral conflict. Even when nationalism surfaced, it remained rarely declamatory. The spy was defined by attentiveness rather than aggression, emerging from social realities. Violence avoided shock value and arrived only when the story demanded it.

The 2010s marked a decisive turning point. When Ek Tha Tiger (2012) arrived, it achieved something deceptively rare. Kabir Khan folded romance into espionage and turned a traditional conflict into an olive branch. Salman Khan’s Tiger was undeniably heroic, yet emotionally porous. His loyalties were tested not just by the nation but by love. The film still involved ISI and R&AW but refused to become a film that divided the two nations. This film eventually laid the groundwork for what would later crystallise as the Yash Raj Films Spy Universe. Around the same time, Neeraj Pandey offered a parallel grammar in Baby (2015), followed by Naam Shabana (2017), which delved into the espionage genre’s nitty-gritty technical processes revolving around intelligence work. Akshay Kumar’s performance in Baby remains one of his most memorable as the clock-ticking adrenaline rush of the film elevates his character. For a brief period, Hindi spy cinema existed in productive tension between these impulses: YRF’s glossy accessibility and Pandey’s realist style. Audiences responded well to both and filmmakers felt emboldened. Then came saturation.

Over the last few years, Hindi cinema has been inundated with spy films and spy-adjacent spectacles—War (2019), Romeo Akbar Walter (2019), Pathaan (2023), Tiger 3 (2023), alongside mid-budget offerings such as Bell Bottom (2021), Code Name: Tiranga (2022), Dhaakad (2022), and Mission Majnu (2023). What once thrived on tension and intelligence began to collapse into a narrow visual and ideological vocabulary. The spy grew louder and the body of the star took centre stage. The enemy became more and more singular as the narrative complexity thinned. The intrigue and moral tension that once held audiences slowly gave way to surface-level glamour and an endless sense of invincibility. Screens filled with slow-motion punches, aerial wire-work, CGI-assisted feats, and thunderous background scores.

A genre that was once driven by secrecy began to prize visibility instead, with character-development taking a back seat. This transformation cannot be disentangled from the political climate in which these films emerged. Contemporary Hindi spy cinema increasingly aligns itself with a muscular nationalism that frames hypermasculinity as moral obligation and violence as patriotic necessity. War (2019) crystallises this turn. Hrithik Roshan’s Kabir is presented as an alpha male—emotionally controlled, physically superior, unquestioned in authority. Tiger Shroff’s Khalid earns validation through endurance and pain rather than intelligence or doubt. The film equated national security with hypermasculinity, transforming espionage into a fantasy of domination. Yet not all recent successes function identically. Pathaan (2023), despite its hyperbolic action and spectacle, was notably less divisive than many of its contemporaries. Much like Ek Tha Tiger (2012), Pathaan tempered its nationalism through affect. Shah Rukh Khan’s aging, wounded spy was defined by vulnerability as much as bravado. The film leaned into self-awareness, camp, and performative excess, allowing spectacle to coexist with emotional accessibility. Crucially, Pathaan avoided sustained demonisation; its antagonism remained fictionalised rather than obsessively real-world specific.

Mid-budget films struggled even more conspicuously. Many of the genre’s recent misfires stumble precisely where Pathaan and Ek Tha Tiger exercised restraint. Mission Majnu (2023), for instance, cloaked itself in realism but ended up flattening its Pakistani characters into ideological props. Bell Bottom (2021) leaned heavily on historical nostalgia while avoiding ethical interrogation. Dhaakad (2022) and Code Name: Tiranga (2022), despite foregrounding female spies, remained trapped within masculinist frameworks where empowerment was measured almost exclusively through violence. These films adopted the surface grammar of espionage without absorbing its moral complexity, leading to viewer exhaustion. Across many recent films, female characters function as emotional anchors, narrative motivators, or symbolic sacrifices. Even when they occupy the frame, decision-making power remains elsewhere.

India has repeatedly attempted its own iterations of James Bond (1962–), Jason Bourne (2002–2016), and Mission: Impossible (1996–). Yet for someone wary of a genre saturated with aggressive masculinity, the search often narrows to the rare moments where its women are allowed interiority. Earlier films like Raazi (2018) located espionage within domestic space, revealing how intelligence work corrodes intimacy and fractures identity. Sehmat’s strength lay in restraint, fear, and moral exhaustion surrounding her patriotic duty. Tabu’s Khufiya (2023) extended this lineage, foregrounding surveillance fatigue and divided loyalties. These films understood that espionage is as much about erosion as execution and women too, make for fantastic spies rather than simply “honey-traps.”

It is within this increasingly polarised landscape that Dhurandhar (2025) arrives. Written and directed by Aditya Dhar, Dhurandhar is an expansive, intense, and technically assured espionage saga that simultaneously recalls the strengths of earlier spy films and embodies the most troubling tendencies of the present. Dhar, who previously delivered Uri: The Surgical Strike (2019), understands propaganda cinema intimately. He knows how to choreograph violence, how to structure emotional payoff, how to mobilise collective memory. Dhurandhar anchors itself in historical trauma, tracing the aftermath of the IC-814 hijacking (1999), before weaving archival footage and verified audio from the Parliament attack (2001) and the 26/11 Mumbai attacks (2008).

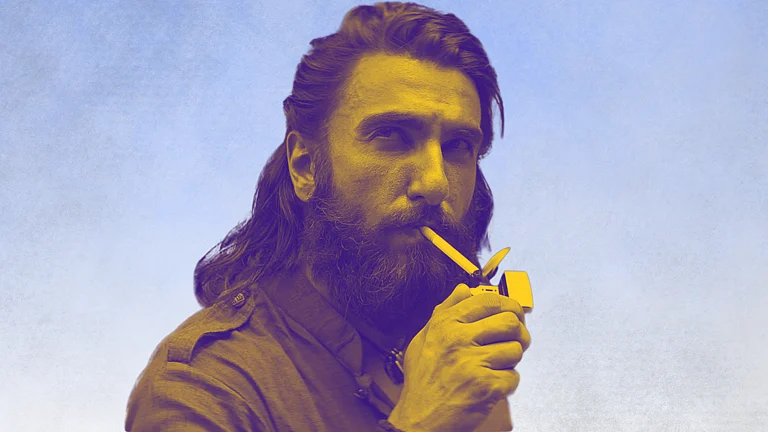

These choices collapse the distance between fiction and lived memory, lending the film documentary-like gravity. At its centre stands Ajay Sanyal (R. Madhavan), an intelligence chief convinced that restraint has failed. His solution is confrontation on enemy turf. Enter Hamza (Ranveer Singh), a long-haired operative positioned as the wounded nation incarnate. “Ghayal hoon isliye ghatak hoon,” he declares—a line that crystallises the film’s emotional logic. Pain becomes power and injury becomes justification.

Technically, Dhurandhar is accomplished. The film’s world is densely populated. Ranveer Singh’s Hamza represents honour and duty, Sanjay Dutt’s Chaudhary Aslam embodies unchecked authority. Arjun Rampal’s Major Iqbal operates as a pragmatic intermediary between gangs and state power. Rakesh Bedi’s Jameel Jamali folds violence into political strategy. The performances are consistently strong, with Akshaye Khanna offering a particularly impressive presence. The violence is raw and deliberately unglamorous, though its sheer volume occasionally overwhelms its intent. Dhar’s pacing falters early but gathers force once the narrative finds its spine. Yet, the film’s strengths are inseparable from its limitations. Set largely in Lyari, Pakistan, Dhurandhar offers little nuance in its portrayal of people or politics. Pakistani characters exist primarily as instruments of cruelty or obsession. Even when the film gestures toward internal fissures—particularly the Pakistan–Balochistan conflict—its gaze remains external and accusatory.

In this regard, Dhurandhar aligns closely with the industrial logic established by Kabir Singh (2019) and Animal (2023). These films demonstrated that aggression, emotional rigidity, and moral absolutism translate into box-office success. Dhurandhar transplants that formula into the spy genre, aestheticising brutality through sound design and slow motion violence. The effectiveness of its impact is precisely why it demands scrutiny. That these films became career-high grossers for their stars is no coincidence. Dhurandhar restores certain pleasures for the viewer—scale, character density, technical confidence and musical texture. It also entrenches its most troubling impulses: Pakistan-centric obsession, Islamophobic undertones, hypermasculine heroism, and an unwavering faith in violence as a moral solution. Dhar’s invocation of Uri’s rhetoric lands exactly as intended, eliciting applause while revealing how predictably fervour can be summoned.

Ultimately, the larger concern extends beyond Dhurandhar. With its second part scheduled for release in 2026, Dhurandhar now functions more as a template. More films will follow, eager to replicate the formula with diminishing nuance and escalating volume. The challenge before Hindi cinema is no longer commercial viability but imaginative courage. Spy films that once relied on complex narratives, moral ambiguity, and high stakes are now using those same tools to increasingly pander to specific demographics, often pitting them against one another. Recovering that goodwill from the audiences will require resisting the certainty of brute force and the comfort of repetition. Dhurandhar demonstrates that craft alone cannot compensate for intent. And intent, when scaled across franchises, shapes not only box-office returns, but collective memory and cultural imagination. The spy genre, and the audiences that once loved it for its shadows, deserve nothing less.