Pre-colonial resistance to Brahminism—the ideological source of caste—often took quasi-religious forms.

The Dravidian movement secularised the caste question and shattered Brahmin hegemony, but it did not annihilate caste.

Reviving transformative politics demands creative synthesis of emancipatory legacies.

Caste in modern India operates simultaneously as a structure of inequality, a means of political mobilisation, and an idiom for ideological projects of social order—deeply entwined with the country’s power structure. Although it appears to draw from Hindu scriptures and pre-modern social organisation, its transformation into a political instrument is largely a product of colonial modernity and democratic politics.

The colonial encounter—through the census, ethnographic surveys, and administrative classifications—crystallised fluid social hierarchies into rigid and enumerated categories, rendering caste both more visible and politically consequential. After independence, theframing of the Constitution, the adoption of representative democracy, and the extension of universal suffrage further reconstituted caste: from a system of social hierarchy into a resource for electoral mobilisation and a language of rights-based claims.

Four major political currents—the Dravidian movement in South India, the Dalit movement led by Ambedkar and his successors, the Communist movement inspired by Marxism, and the Hindutva movement articulated by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)—have each engaged with caste. While the first three sought to transcend or dismantle caste within their respective ideological frameworks, each was constrained by its own theoretical and political limits. Hindutva, by contrast, re-legitimised hierarchy under the guise of cultural nationalism, portraying caste as a form of organic and harmonious differentiation.

Understanding these divergent approaches is vital today, for the contemporary crisis of caste—evident in the persistence of atrocities, the politics of symbolic inclusion without structural transformation, and the ascendancy of majoritarian violence—reveals both the failures of emancipatory movements and the success of reactionary ones. The struggle against caste inequality thus remains central to the unfinished project of Indian democracy.

Historical Context

Pre-colonial resistance to Brahminism—the ideological source of caste—often took quasi-religious forms. The Bhakti movement, emerging across regions from the early medieval period, embodied one such multiform revolt. Its diverse traditions—from the Tamil Ālvārs and Nāyanmārs to Basavanna’s Vīraśaivas in Karnataka, the Varkaris of Maharashtra, and the North-Indian Sants—collectively subverted caste through devotional egalitarianism. They challenged ritual purity, priestly authority, and Sanskritic exclusivity by affirming vernacular devotion. Saints such as Basavanna, Kabir, Tukaram, Chokhamela, Ravidas and Mirabai rejected the idea that spiritual worth derived from birth or ritual status. Though couched in religious idioms, Bhakti’s ethical core was social dissent—a protest against Brahminical monopoly and an affirmation of moral equality.

Even after Bhakti, anti-caste assertion continued through religious reinterpretation. From Harichand Thakur’s Matua sect in mid-19th-century East Bengal—which reimagined Vaishnava devotion to affirm Namashudra dignity—to Jotiba Phule’s Shudra-Ati-Shudra versus Shetji-Bhatji critique culminating in his Sarvajanik Satya Dharma, and finally to Ambedkar’s Navayana Buddhism, which transformed spiritual practice into a doctrine of social emancipation—the pattern persisted. These movements recognised Brahminism’s ideological power and sought to neutralise it by reconstituting religion itself. India’s long struggle against caste thus advanced not through atheistic rejection but through a reimagined religiosity that relocated the divine from ritual to morality.

Modern political mobilisation around caste arose from colonial transformations that reconfigured caste into a modern political category. Through census operations and ethnographic surveys, the British fixed fluid hierarchies into enumerated identities, making caste more legible to the state and usable for politics. Early 20th-century mobilisations reflected this shift: the Justice Party (1916) articulated non-Brahmin interests, prefiguring the Dravidian movement, while Depressed Classes associations demanded representation and reform, laying the groundwork for Ambedkar’s politics.

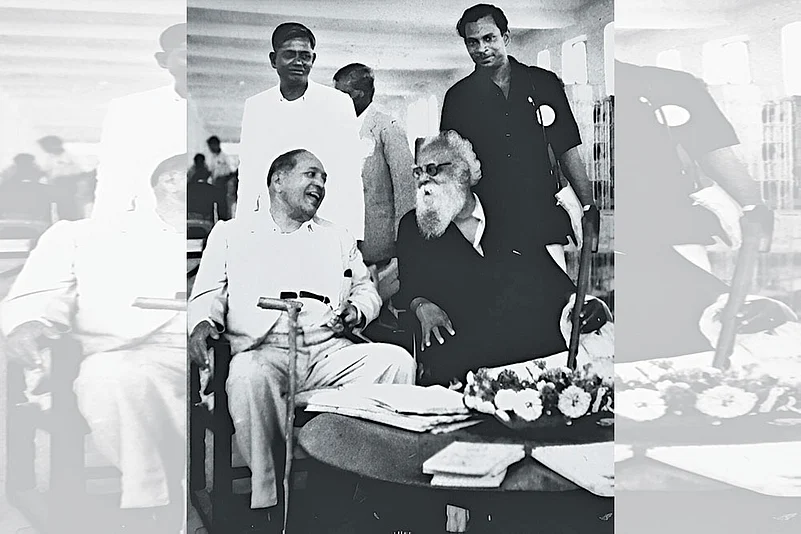

Notably, three of the four major movements examined here emerged in 1925—the RSS, Periyar’s Self-Respect movement, and the Communist Party—with Ambedkar’s initiative preceding them by a year through the Bahishkrut Hitakarini Sabha. The decades from the 1920s to 1950s saw the crystallisation of distinct ideological responses: Periyar attacked Brahminism and Hindu orthodoxy through a rationalist Dravidian identity; Ambedkar’s organisations evolved from caste annihilation to civil rights and representation; the Communists subsumed caste under class; and the RSS sacralised varna hierarchy as the organic unity of Hindu society.

These movements unfolded amid sharp debates—Gandhian reform versus Ambedkarite radicalism, Congress nationalism versus Hindu nationalism, and class struggle versus caste mobilisation. Colonial policies such as reserved seats, the Poona Pact (1932) and the Government of India Act (1935) institutionalised caste as a category of representation, creating new openings for empowerment but also new forms of elite capture. Whether caste politics would ultimately abolish or perpetuate caste became the defining dilemma of postcolonial India.

The Dravidian Movement

The Dravidian movement, rooted in Periyar’s Self-Respect movement and later institutionalised through the Dravidar Kazhagam (DK) and the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), addressed caste as a form of ideological domination rather than mere social hierarchy. For Periyar, Brahminical power rested on religious hegemony—the sanctity accorded to scriptures that legitimised subordination. His atheism and rationalism thus became strategic weapons: to annihilate caste, religion itself had to be dethroned.

Periyar’s construction of Dravidian identity as indigenous and rationalist directly opposed the Aryan-Brahmin order of Sanskritic Hinduism. This Dravidian-Aryan dichotomy, while historically questionable, proved politically powerful: it provided non-Brahmins with an alternative identity and legitimacy independent of Hindu religious frameworks. Rejecting Sanskritisation, he called for de-Brahminisation through inter-caste marriage, women’s emancipation and anti-superstition. The movement’s cultural politics—Tamil linguistic pride, critique of northern domination, and attack on priestly authority—fused social justice with regional assertion. It succeeded in creating a counter-hegemonic political culture in which open defence of Brahmin privilege became untenable.

The Justice Party’s early reforms (1920-37) and subsequent DMK regimes institutionalised reservations in education and employment, eroding Brahmin monopoly and enabling non-Brahmin advancement. After independence, DMK governments deepened this social justice regime, extending reservations that transformed Tamil Nadu’s bureaucracy, education and politics. Brahmins, who had once dominated these spheres, rapidly lost ground, while intermediate castes such as Mudaliars, Gounders and Nadars gained unprecedented access to state power and opportunity.

Born of Ambedkar’s radical critique of caste and carried forward through post-Ambedkar formations, the Dalit movement represents the most fundamental challenge to the caste hierarchy.

The movement successfully created a counter-hegemonic political culture where explicit advocacy of Brahmin interests became politically suicidal. Unlike in North India where upper-caste dominance persisted through both the Congress and later the BJP, Tamil Nadu politics became genuinely competitive among non-Brahmin castes, with Brahmins reduced to political marginality.Yet, caste did not disappear—it reorganised. The very castes empowered by Dravidian rule (Vanniyars, Thevars, Gounders and Nadars) perpetuated violence and exclusion of Dalits. Despite rhetorical inclusion, Dalits remained politically weak and socially vulnerable; atrocities like Kilvenmani (1968), Kodiyankulam (1995) and Melavalavu (1997) exposed the persistence of caste beneath egalitarian slogans. The movement that had dismantled Brahmin supremacy stopped short of challenging hierarchy itself.

As the DMK and the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) consolidated power, radical rationalism gave way to electoral pragmatism. Periyar’s revolutionary atheism was reduced to ritualised gestures—self-respect marriages, Tamil symbolism, and welfare populism—while structural transformation receded. Regionalism, too, curtailed universalism: by framing caste as an Aryan-Dravidian conflict, the movement ignored intra-Dravidian oppression.

The Dravidian movement secularised the caste question and shattered Brahmin hegemony, but it did not annihilate caste. It replaced one dominance with another, empowering intermediate castes while leaving Dalits subordinated. Its gains—in education, representation and welfare—were substantial yet partial, addressing the cultural and political symptoms of caste without altering its economic and structural foundations. Ultimately, the movement exposed the paradox of regional radicalism: it dismantled Brahminism’s monopoly but not caste’s logic, opening a space for equality yet falling short of the total social revolution.

The Dalit Movement

Born of Ambedkar’s radical critique of caste and carried forward through diverse post-Ambedkar formations, the Dalit movement represents the most fundamental challenge to India’s caste hierarchy. Unlike Hindu reformist or class-based communist approaches, it treated caste itself as the primary structure of domination—a system demanding annihilation, not reform. Yet, over time, it settled for representation within existing structures rather than questioning their foundations, eventually assuming status-quoist positions.Ambedkar’s rupture with both Hindu reformism and Marxist economism defined the movement’s distinctive character. Against Hindu reformers like Gandhi, who sought to abolish untouchability while preserving varna (recast as a division of labour without hierarchy), Ambedkar argued that untouchability was no aberration but the logical culmination of caste. “Caste,” he wrote, “is not a wall of bricks…it is a notion; a state of mind.” Rooted in Hindu scriptures, it could not be reformed; it had to be destroyed along with its religious foundations.

Against Marxists who undermined caste, treating it as derivative of economic relations represented by class, Ambedkar contended that caste was itself a mode of production and a system of exploitation irreducible to class. In his 1936 exchange with the Communist Party, he argued that caste shaped property relations, labour organisation and surplus extraction in ways the Marxist binaries

of capitalist and worker could not capture. Caste oppression, he insisted, was simultaneously economic, cultural, psychological and spiritual—requiring transformation on all these fronts.

Ambedkar’s vision thus combined constitutional democracy with minority rights; reservations in education, employment and politics as compensatory justice;education as a means to generate counter-consciousness; religious conversion—culminating in Buddhism—to reject Hinduism’s moral order; and economic reorganisation on socialist principles.

This comprehensive vision understood that caste operated simultaneously as cultural identity, economic system, political exclusion, psychological degradation and ideological justification—therefore requiring multi-dimensional resistance addressing all these aspects simultaneously.

Post-Ambedkar Trajectory

After his death in 1956, the movement splintered under the guise of ideology, in reality driven by rank opportunism among its leaders. The Republican Party of India (RPI) was soon divided, with one faction invoking the “ideology of Ambedkar” to accuse the other—those advocating struggles for land for the landless—of being communists. The Dalit Panthers, formed in 1972 by educated Dalit youth inspired by the Black Panther Party in the United States and by Ambedkar’s radical legacy, offered a comprehensive critique of caste, class, and patriarchy, linking Dalit liberation to global struggles against capitalism and imperialism. By defining “Dalit” to include all oppressed peoples, they infused a new militancy into Dalit politics. Yet internal discord and state repression curtailed their influence, and they too fractured along the Ambedkarism–communism divide, with one group accusing the other of being Marxist and betraying Ambedkar’s path of Buddhism. This recurring opposition between Marxism and Ambedkarism eventually drifted the Dalit movement into the reactionary camps, including that of Brahminism.

Parallel to the Panthers, Kanshiram charted an organisational path—mobilising educated Dalits through BAMCEF, creating DS4 as a preparatory front, and finally forming the Bahujan Samaj Party (1984). By converting Ambedkarite assertion into electoral power, the BSP advanced the “Bahujan” thesis—uniting Dalits, OBCs, Adivasis and minorities, roughly 85 per cent of India’s population, into a political majority demanding proportional representation. Under Mayawati, the BSP’s ascent in Uttar Pradesh symbolised a historic reversal: Dalits governed rather than petitioned. Ambedkar statues, Dalit bureaucrats and a new cultural pride signified a symbolic revolution, while welfare measures delivered tangible benefits.

Grounded in Marxist materialism, the Communist movement offered a powerful critique of capitalism but failed to grasp caste within its revolutionary schema—reducing it to a mere superstructural residue.

Yet, profound contradictions endured: class differentiation within Dalits created divides between a rising middle class, a product of reservation policy, and the labouring poor.

Identity-based mobilisation, while empowering, often froze caste as a permanent political category. Organisational fragmentation weakened the movement against disciplined forces like the RSS.

Coalitional compromises—especially BSP’s alliances with the BJP—diluted Ambedkar’s emancipatory spirit. The Dalit movement transformed caste into a national question of justice, created legal safeguards, and generated a rich counter-hegemonic tradition. Yet, its translation into representational politics fell short of Ambedkar’s vision of annihilation. Instead of eroding caste consciousness, it often deepened it through identity fixation and symbolism. Persistent atrocities and economic exclusion expose the limits of symbolic empowerment within structures that remain Brahminical at their core. The unresolved question remains: can caste be annihilated through democratic reform or religious rhetoric without confronting the power structure itself? In drifting from Ambedkar’s revolutionary goal—to dismantle Hinduism’s ideological power and rebuild society on egalitarian foundations—the movement achieved assertion but not transformation.

The Communist Movement

Grounded in Marxist materialism, the Communist movement offered a powerful critique of capitalism but failed to grasp caste within its revolutionary schema—reducing it to a mere superstructural residue. Classical Marxism’s insistence on class primacy, viewing other hierarchies as pre-capitalist survivals, proved a major blind spot in the Indian context.

For Marxists, class—defined by one’s relation to the means of production—was the motor of history. Caste, seen as a feudal relic, was expected to wither away under capitalism. Yet capitalist development in India reconstituted rather than abolished caste: Dalits remained confined to the most degrading labour, while land, credit and enterprise stayed monopolised by the upper castes. Even in cities, segregation and stigma persisted. Far from disappearing, caste adapted to capitalism, becoming one of its key instruments of labour control and social discipline.

Lenin’s broader understanding of class, which incorporated ideology and consciousness, could have opened a theoretical avenue to integrate caste into class analysis. Indian communists, however, failed to grasp its import and largely neglected this possibility, treating caste as a diversion from class struggle and thereby alienating vast Dalit and lower-caste constituencies.

Communist-led struggles—Telangana (1946–51), Tebhaga (1946-47) and Naxalbari (1967)—demonstrated both the potential and limits of class-based mobilisation. These movements did unite Dalits, Adivasis and landless peasants in anti-feudal struggles, but the upper-caste composition of leadership and theoretical rigidity often prevented sustained solidarity. In Kerala, communist governments advanced education, land reform and labour rights, yet caste exclusion endured beneath socialist rhetoric, revealing the tenacity of Brahminical hierarchy even within egalitarian frameworks.

Ambedkar and the Left

The Ambedkar-Left divergence stemmed partly from overlapping social bases but deeper ideological conflict. Ambedkar accused communists of “economic reductionism”, insisting that economic equality without ideological transformation would leave caste intact. Communists, in turn, dismissed Ambedkarites as purveyors of “bourgeois identity politics” that fragmented class unity. The divide was thus structural: for Ambedkar, caste was the primary social contradiction; for Marxists, it was derivative of class. Their strategies reflected this difference—Ambedkar championed autonomous Dalit organisation and constitutional justice, while the Left privileged class revolution and economic restructuring.

In recent decades, scholars and activists have attempted a synthesis between Marxism and Ambedkarism, exploring how caste shapes capital accumulation, labour control and political economy. They contend that any meaningful socialism in India must treat caste as constitutive of capitalism, while Dalit emancipation must engage class exploitation within its own fold. Yet, this discourse has often faltered—failing to provide a coherent theoretical articulation of caste within the Marxian framework, and constrained by the entrenched belief that Ambedkar and Marx stood in opposition.

The Communist movement supplied the grammar of economic justice—class struggle, redistribution, and collective rights—but its blindness to caste curtailed its transformative reach. Material gains through land reforms and welfare improved Dalit conditions without dismantling the caste hierarchy that persisted even within party structures. The endurance of caste in Communist-led states underscores the inadequacy of a purely class approach. Genuine transformation in India demands a theoretical and practical synthesis—an anti-caste, anti-capitalist politics capable of confronting both structures of domination simultaneously.

The Hindutva Movement

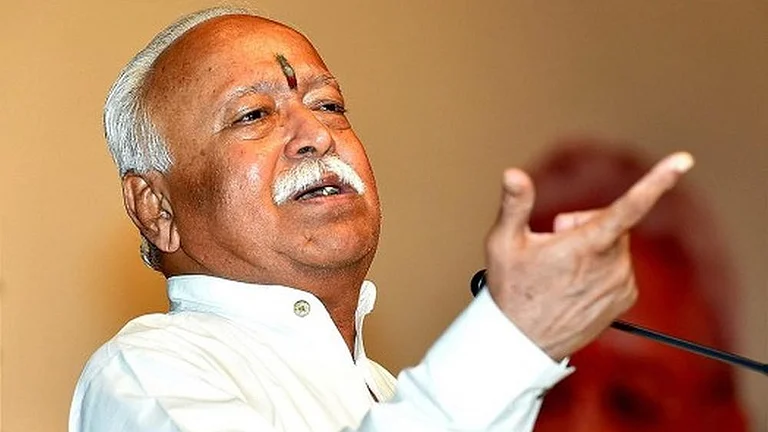

The Hindutva movement—ideologically articulated by Savarkar and Golwalkar and institutionally embodied in the RSS and its political arm, the BJP—represents a fundamentally different relation to caste than the emancipatory movements preceding it. Instead of challenging hierarchy, it re-functionalised caste as an “organic order” essential for Hindu unity, weaponising religious nationalism to defend hierarchy while pretending to transcend it.

Savarkar’s Hindutva: Who is a Hindu? (1923) defined Hindu identity not by belief but by cultural-civilisational belonging—anyone for whom India was both pitribhumi (fatherland) and punyabhumi (holy land). This excluded Muslims and Christians, whose sacred lands lay elsewhere, while enfolding all Hindu castes within a common national identity. Though Savarkar denounced untouchability, his proposed “reform” sought to discipline caste, not destroy it. His notion of varna as a “natural division of labour” and “organic unity” exposed his reformism without egalitarianism.

M.S. Golwalkar’s We, or Our Nationhood Defined (1939) and Bunch of Thoughts (1966) carried this logic to its conclusion. He celebrated varna as divinely ordained, reflecting innate differences in aptitude and temperament, and condemned Ambedkarite or Marxist efforts to abolish it as alien assaults on Hindu civilisation’s “natural harmony.” For him, hierarchy was not oppression but cosmic order.

Founded in 1925 amid the twin pressures of Muslim assertion and lower-caste mobilisation, the RSS thus emerged as a Brahminical counter-mobilisation—seeking Hindu consolidation under upper-caste stewardship. Hindu unity was to be achieved not by dismantling hierarchy but by domesticating dissent.

The RSS-BJP’s caste politics operates through four interlocking strategies:

Symbolic inclusion, which entails co-opting OBCs and Dalits through visible representation (Narendra Modi, Ram Nath Kovind, Draupadi Murmu) while preserving upper-caste dominance.

Antyodaya rhetoric—Deendayal Upadhyaya’s paternalistic “uplift of the last person” displaces Ambedkarite radicalism with moral charity, preserving caste legitimacy while softening its appearance.

True anti-caste politics must confront caste as a total system—cultural, economic, and psychological—rather than presuming it will dissolve through secondary reforms.

Manufactured external threat—the slogan ‘Hindu khatre mein hai’ converts potential inter-caste solidarity into anti-Muslim animus, demanding subordination of internal divisions to religious unity.

Rechanneling—under neoliberalism, dispossession and insecurity find psychological relief in cultural nationalism. The RSS’s network of shakhas, welfare arms and social services provide belonging and order where progressive movements often fail to reach.

This synthesis has reconfigured caste politics. Hierarchy persists—and even intensifies—yet, appears as the expression of Hindu unity, not its violation. Caste atrocities and everyday humiliations are reframed as defence of Sanatan Dharma, while impunity for perpetrators is integral to the system, not a bureaucratic lapse.

Recent incidents illustrate this ethos. Within a single week in October, a lawyer with known Hindutva leanings hurled a shoe at CJI B.R. Gavai in court, shouting “Sanatan ka apmaan, nahi sahega Hindustan,” and faced no action. Around the same time, ADG PuS died by suicide after enduring casteist abuse from nine officers named in his note; his IAS officer wife’s demand for their arrest under the Atrocities Act was ignored. Such episodes expose not aberrations but the sanctioned impunity of casteist elements under the present regime.

The appropriation of Ambedkar marks Hindutva’s most cynical gesture. By celebrating his birth anniversary, quoting his anti-Congress remarks, and recasting him as a Hindu nationalist, the BJP-RSS hollow out his radicalism—his rejection of Hinduism, his warning against Hindu Raj, and his call for caste annihilation—and redeploy his image to legitimise the order he sought to dismantle.

Hindutva’s ingenuity lies in sacralising hierarchy—turning graded inequality into the moral foundation of nationalism. Through selective inclusion, welfare populism and organised violence masked as cultural defence, it induces the subordinated to defend their own subordination. What appears as Hindu unity is, in substance, Brahminical hegemony in nationalist form.

The Future of Caste Politics in India

Juxtaposing the major movements reveals distinct conceptions of caste and divergent modes of engagement.The Dravidian movement saw caste as Brahminical domination; its rationalism weakened priestly power but left intra-non-Brahmin hierarchies intact.

The Dalit movement, grounded in Ambedkar’s moral-political critique, treated caste as graded injustice demanding annihilation, not reform. Its fragmentation and electoral co-optation, however, blunted its transformative edge.

The Communist movement subordinated caste to class—achieving economic redistribution but failing to recognise caste as a pervasive and autonomous structure of domination.

The Hindutva movement, conversely, sanctifies hierarchy as cultural order—absorbing subordinated castes into a Brahminical nationalism that re-legitimises inequality.

The comparative lesson is stark: only the Ambedkarite and Periyarite traditions posed existential challenges to caste. The others—Dravidian, Communist and Hindutva—accommodated it within frameworks of regionalism, class, or religious nationalism. True anti-caste politics must confront caste as a total system—cultural, economic, and psychological—rather than presuming it will dissolve through secondary reforms.

Caste politics today embodies a deep paradox. Equality and representation have expanded constitutionally, yet atrocities multiply and hierarchies tighten. Neoliberal privatisation has curtailed the reach of reservation, while identity politics substitutes recognition for redistribution.

Hindutva’s appropriation of caste—token elevation of Dalits and OBCs, ritual invocation of Ambedkar, and systemic violence justified as cultural defence—represents the gravest counter-revolution against equality.

Reviving transformative politics demands creative synthesis of emancipatory legacies. From Ambedkar, the call to annihilate caste and build autonomous organisation; from Periyar, the rationalist challenge to religious authority; and from Marxism, the structural analysis of exploitation and collective solidarity. The movement must recognise that contemporary caste differs fundamentally from its classical form—it is now inseparable from the modern power structure and its operations. Its annihilation, therefore, demands not reform but a radical restructuring of society—a revolution. Piecemeal or incremental approaches would only perpetuate the crisis. The viable path lies in revitalising the revolutionary framework: redefining class to encompass caste and other axes of subordination such as gender and race, and drawing upon the insights of Ambedkar, Periyar and other emancipatory traditions to forge a unified struggle within the broader logic of class struggle.

(Views expressed are personal)

This story appeared as March of Movements in Outlook’s December 11 issue, Dravida, which captures these tensions that shape the state at this crossroads as it chronicles the past and future of Dravidian politics in the state.