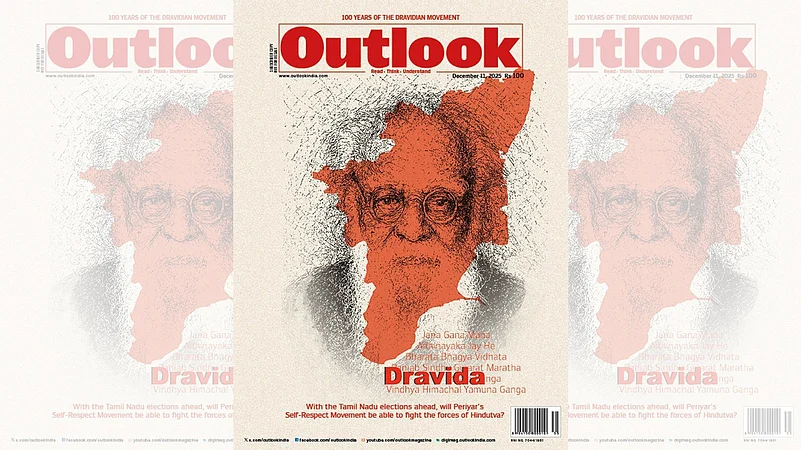

Testing the foundations of Tamil identity, rationalism and social justice, Periyar’s Self-Respect legacy confronts a Hindutva push

Caste churn & widening urban–rural divides expose the contradictions within the state’s celebrated Dravidian model.

Gen Z and women voters demand opportunity over rhetoric, challenging the DMK-AIADMK duopoly as new players reshape the contest.

“If god is the root cause for our degradation destroy that god. If it is religion, destroy it. If it is Manu Darma, Gita, or any other Mythology (Purana), burn them to ashes. If it is temple, tank, or festival, boycott them.”

― Periyar

That’s how it began. A 100 years ago, when the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) first began to imagine India as Hindu Rashtra, in the South, another movement based on dignity and opposed to gods who were used to perpetuate the caste system was emerging. Over the last 100 years, a lot has changed. The Ram temple in Ayodhya has been consecrated, Bharat Mata is now official with the Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi releasing a Rs. 100 coin with the figure carved on it to mark the centenary of the RSS.

Dravidian politics has always been at the core of Tamil Nadu politics, which has resisted all forms of imposition from the North, including Hindi and Hindutva politics. But cracks have begun to appear in their resolve and their resistance with the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP’s) Hindu nationalist politics spreading across India aiming to unite all under the banner of religion and their inability and perhaps reluctance to address the issues of the Dalit community.

Tamil Nadu, which goes to elections next year, is at the forefront of defending federalism that is also a constitutional provision. In that, lies its identity and its strength and in that, lies the dignity of the Constitution.

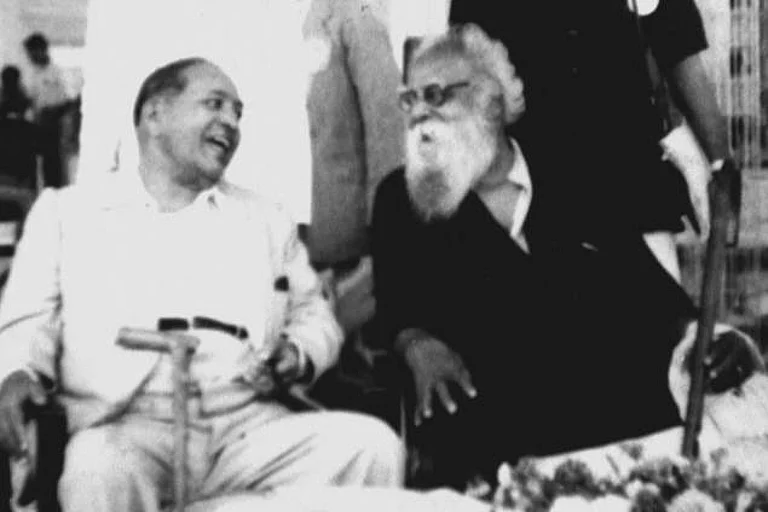

The Self-Respect Movement that was started by E.V. Ramasamy ‘Periyar’ and S. Ramanathan in 1925 following their differences with the Congress party on matters related to caste and proportional representation, is now facing an uncertain future where the redemption must come from their ability to reform and redeem.

Three institutions were formalised and announced. The RSS, the Communist Party of India, and the Self-Respect Movement. They woke up many souls in different parts and in different ways and as people swore their loyalty to one or the other, the clashes between them became more pronounced and each of these institutions and movements claimed to define India and Indians and each in their own way has framed the question of who is an Indian based on their ideas and ideologies. While the Left is faced with an identity crisis, the RSS has not only survived but has grown and with the BJP in power at the Centre and in several states.

With the Tamil Nadu elections ahead, will Periyar’s Self-Respect Movement be able to fight the forces of Hindutva? How will and how well will it negotiate between promise, performance, and an ideological legacy? Dravidian politics, once the engine of social justice and linguistic assertion, now confronts the strain of competing populisms, shifting caste equations, and younger, impatient electorate, less forgiving of rhetoric.

The mandate of the coming months may renew hopes. But the burdens are heavy. Jobs, caste representation, regional pride, and the anxieties and the aspirations of Gen Z press harder than ever. Tamil Nadu faces the uneasy truth that its celebrated model that was built on welfare and rights-based entitlements is under unprecedented scrutiny.

Even with one of India’s strongest social indices, the state carries several contradictions. Unemployment among youth remains among an issue. Fiscal deficit has widened. Welfare expenditure has climbed. Revenues struggle to keep pace. Urban-rural divides deepen. While Chennai races ahead, northern and western districts lag in health outcomes, employment opportunities, and public infrastructure.

Caste equations continue to remain combustible. Vanniyars, Thevars, Gounders, and Dalit sub-castes continue to shape electoral margins. For women, the welfare promise remains central. But their participation in the workforce is shrinking, thus narrowing economic agency. And a million young voters who grew up on the internet are demanding a politics that offers opportunity and not only subsidies.

The ruling party Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) under M.K. Stalin champions its ‘Dravidian Model 2.0’ which is a blend of welfare populism and digital governance. The party seeks to reaffirm its commitment to equity as it courts younger voters through tech-savvy outreach, and free bus rides and expanded health schemes for women.

Across the aisle, the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) grapples with leadership churn and factional battles. At the same time, it attempts to revive its grassroots connect. And hovering on the margins, the BJP pushes its Hindutva narrative, hoping to puncture Tamil Nadu’s Dravidian fortress. New entrants like Vijay’s Tamilaga Vetri Kazhagam (TVK) and Seeman’s Naam Tamilar Katchi (NTK) inject unpredictability into the electoral arithmetic.

Outlook’s December 11 issue, Dravida, captures these tensions that shape the state at this crossroads as it chronicles the past and future of Dravidian politics in the state. Anand Teltumbde examines how caste continues to unsettle India’s social justice movements. In The Dignity in Self-Respect, S.V. Rajadurai how the movement continues to shape the social, civil and public realms of the state. Perumal Murugan takes the story to the villages, revealing how the movement reshaped everyday relations and rural imaginations.

In The Flow of Thirukkural, Snigdhendu Bhattacharya follows the evolution of these movements across decades, while P.A. Krishnan revisits the imprisonment of Periyar and the political tremors it unleashed. In The Outpost, Mohammad Ali studies the Hindutva challenge to the Dravidian model, and Fozia Yasin in The Lesser Daughters of the Goddess turns to one of Tamil society’s deepest wounds — the Devadasi system — and how it continues to test the region’s claims of social reform.

In the Overlap section, this issue also widens its lens. Ruchira Gupta writes the Fairytale of a Fallow Land, capturing Bihar’s unfinished struggles. Harish Khare examines why the Delhi Police have come to see intellectuals as dangerous. And Vijay Prashad argues that the global war on drugs is, in truth, a war against the poor.

As the state stands at the edge of another reconfiguration, Dravidian politics stands at a defining moment. With the fall of Bihar in the recently concluded assembly elections to the BJP-led alliance, which once again highlights the fractured landscape of caste and social engineering to pitch one against the other, Tamil Nadu is caught between its historic promise of social justice and the compulsions of competitive populism. And the coming months will reveal whether this movement reinvents itself or risks dilution in the face of new aspirations and whether the legacy of Periyar will continue to challenge the outreach of religion-based politics.