Over a century, the RSS has reframed its caste narrative—from “purity” rooted in Brahmanical hierarchy to “harmony” and “inclusivity”—yet its ideological core of cultural homogenisation under Hindutva largely remains intact.

While the RSS highlights social outreach through initiatives like Sewa Bharati and the Panch Parivartan programme, critics argue this inclusivity demands assimilation into the Hindu Rashtra identity rather than dismantling caste hierarchies.

From drones in Shastra Pujan rituals to Dalit outreach yatras post-2024 elections, the organisation’s new language and symbols project modernity and unity—but often conceal an enduring structure of graded inequality beneath the surface of reform.

“Harmony with caste,” drawn from Brahminical culture, is what the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) is believed by its pracharaks to have evolved towards over the past hundred years. As the lights dim under the shadow of the Dhwaj, Nagpur sits in a curious calm of non-violence as the evening of October 1 settles over Deekshabhoomi. Thousands gather from Yavatmal and Amravati to pronounce the words of B.R. Ambedkar and to crusade against caste slurs that still haunt them. But this time, they are not alone.

Ram Nath Kovind, former President of India, bows before heading to the RSS Vijayadashami celebration scheduled for the next day marking the first of the three places he bowed his head that evening – the other two being at the Hegdewar’s memorial and the Shastra Pooja.

Earlier on September 27, the RSS organised rallies which set off from three corners of Nagpur — Yashwant Stadium, the Indian Hockey Ground, and Kasturchand Park — threading through the city’s veins towards Variety Square, where the statue of Mahatma Gandhi stands sentinel.

One of those marching is eighteen-year-old Vikram Singh who feels aflame with his great-grandfather’s legacy. The pathasanchalan, the annual march, is unlike anything he had imagined: drums beating steady as a heart, batons thudding in synchrony against the asphalt.

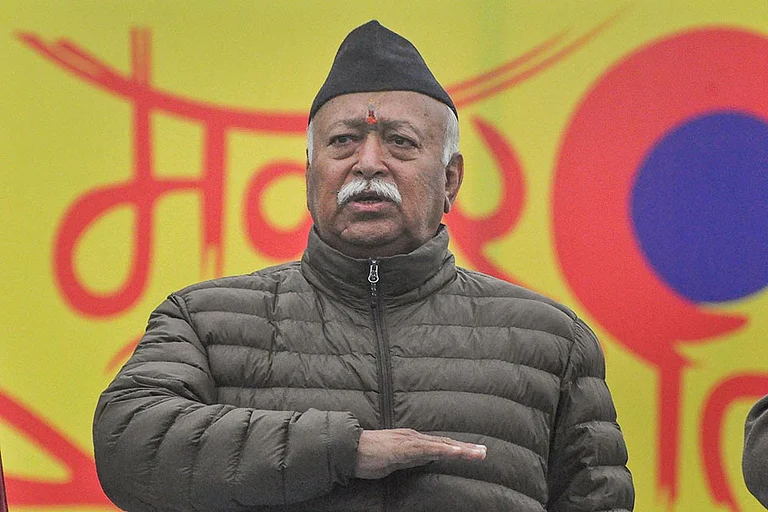

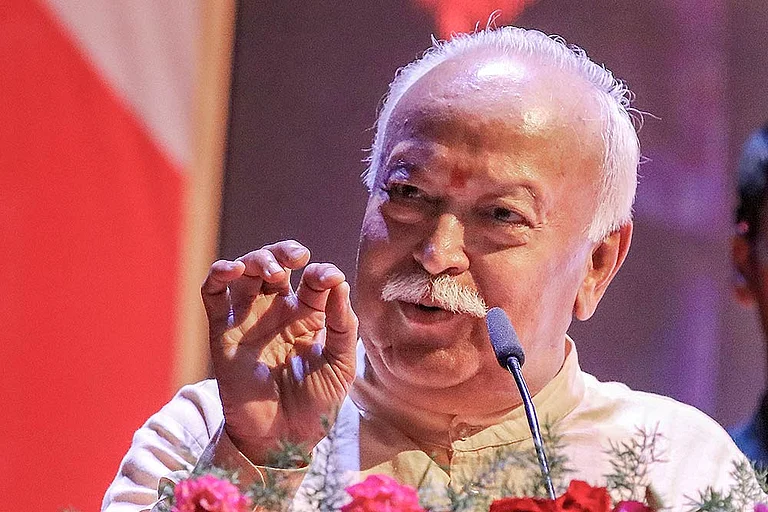

By 8 pm, all three processions converge — a sea of 21,000 swayamsevaks standing shoulder to shoulder beneath the sodium lights of Sitabuldi. From a raised platform, Dr Mohan Bhagwat surveys the crowd, flanked by other senior leaders. A conch blows; silence falls; the prayer begins.

Vikram’s voice trembles at first, then steadies, while he remembers his grandfather teaching him the same prayer on dusky evenings. “This is not just a song, beta,” he had said, “it’s a sankalp — a promise.” The same hymn now fills the Vijayadashami parade, where Mohan Bhagwat and Ram Nath Kovind bow in the Shastra Pujan ritual — this time, notably, alongside replicas of drones and missiles.

Shifting Words, Steady Ideology

‘Hindubhumi, Hindurashtra, Hindutva’ are the terms that coil around the organisation’s foundation. “The Sangh is not the largest national entity; rather, it is the biggest civilisational force,” says Dilip Deodhar, an RSS researcher from Nagpur, invoking historian Arnold Toynbee’s theory of the “creative minority”, those small visionary groups that shape the course of civilisation.

Disarming the Aryan Invasion theory, Deodhar adds, “The Aryan Invasion is another hoax, rightly understood by the RSS.” Echoing Bhagwat’s recent speeches, he insists that “the DNA of all Indians, dating back 40,000 years, is the same.”

The RSS now frequently quotes this genetic unity, a stark contrast to its early leadership’s views. In 1938, Madhavrao Sadashivrao Golwalkar, the organisation’s second Sarsanghchalak, had praised Adolf Hitler for maintaining “the purity of the Aryan race and its culture.”

That purity rhetoric seems to have been repackaged. Take Arogya Bharati, the RSS’s health wing, which launched the Garbh Vigyan Sanskar project in 2017, a programme to create a “customised” child: fair, tall, and intelligent. It prescribes purification rituals, planetary timing for conception, abstinence, and strict dietary rules. The project’s tagline reads: “Baby by choice, not by chance.”

Old Threads, New Promises

“I don’t know about that,” says Vikram, laughing. “I’m not a history student, but I wear a janau.” The sacred thread, taught by his family, marks the “second birth” (dvija) of a person — the start of a life guided by dharma.

“But my friend at the shakha,” he chuckles, “doesn’t wear the thread, so of course I’m purer than him. Just joking.” He quotes K.B. Hedgewar, the RSS founder: “Every swayamsevak is a dvija, those reborn in the service of the nation.”

The organisation’s researchers, however, reinterpret caste differently now. “Those ruling today are the Vaishyas, soon it will be the turn of the Shudras and women,” says Deodhar. “In the RSS’s theology, all are equal.” He aligns this with Ambedkar’s Who Were the Shudras?, yet the contradiction lingers: does theoretical equality erase lived casteism?

Inclusion or Assimilation?

The RSS often cites its social work wings Vanvasi Kalyan Ashram, Vidya Bharati, and Sewa Bharati as proof of inclusivity. Founded between the 1950s and 1980s, they focus on education, healthcare, and welfare among tribal and Dalit communities. But as critics note, inclusion here often means absorption into the Hindutva fold, not liberation from it.

Bhawar Meghwanshi, who joined an RSS shakha in Bhilwara at thirteen, recalls being drawn by the games, not ideology. Later, when he sought to become a pracharak, he was rejected and RSS volunteers refused to eat at his Dalit household. “They said they’d eat later in the next village,” he remembers. “Later I learned they had thrown the food away.”

“One might argue that Narendra Modi was a full-time pracharak despite belonging to an Other Backward Caste,” he adds, “but he became one long before his caste was recognised as OBC.”

The Modh Ghanchi community was officially added to Gujarat’s OBC list only in 1994 — decades after Modi’s initiation. “So where is Ambedkar’s annihilation of caste?” Meghwanshi asks. “Even our inclusion is an afterthought.”

New Language of the Old Faith

For others like Mandar Pattekar from Mumbai, the shakha experience was inclusive and different. He found it formative, instilling discipline, civic duty, and moral grounding. “Children from different classes stood together,” he says. Pattekar highlighted lessons in resilience, attention to detail, noting experiences where lower-income children were treated with reverence by higher-caste adults during rituals. “You learned respect and service.”

Bhagwat said the Sangh’s founding principle was that social change begins with individual conduct. “The RSS’s mission is to create individuals of character who inspire change through their actions,” he noted. He described shakhas as the base of discipline and community life, adding that the RSS had stayed away from politics to focus on character building, and would expand daily shakhas in its centenary year.

Ram Nath Kovind spoke about the Panch Parivartan initiative, centred on social harmony, family values, environmental care, self-awareness, and Swadeshi discipline. He called the Ekatmata Stotra “a testament to the RSS’s inclusive vision,” highlighting its mention of Valmiki, Ekalavya, Sant Ravidas, and Ambedkar. The initiative’s Social Harmony pillar seeks to end caste discrimination and promote equal access to social and religious spaces.

But this harmony, critics argue, is structured, conditional upon acceptance of Hindutva. “The purity culture has drifted to inclusivity,” says scholar and RSS critic Ram Puniyani. “They now say Hindutva welcomes everyone, but you must first enter the lanes of Hindu Rashtra. They’ll make you part of themselves.”

After the 2024 elections, the RSS and its affiliate, the Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP), intensified outreach to Dalit communities through padyatras, satsangs, and Dharm Sansads across 9,000 subdivisions — seeking to win back those who had turned to the INDIA coalition. Saints and sadhus visited Dalit homes, share meals, and hold prayer gatherings to foster a sense of unity.

“It’s the same strategy as the Ram Temple movement,” says Puniyani, “using culture and devotion to reclaim the narrative — the double speak of equality through hierarchy.”

The RSS’s vocabulary has changed. Now “harmony” replaces “purity”, “inclusivity” replaces “discipline”. But the subtext remains: unity under one identity, one civilisation, one faith.

Between the shakha chants and the Shastra Pujan drones, the question echoes, has the RSS evolved beyond caste, or simply rewritten its grammar?