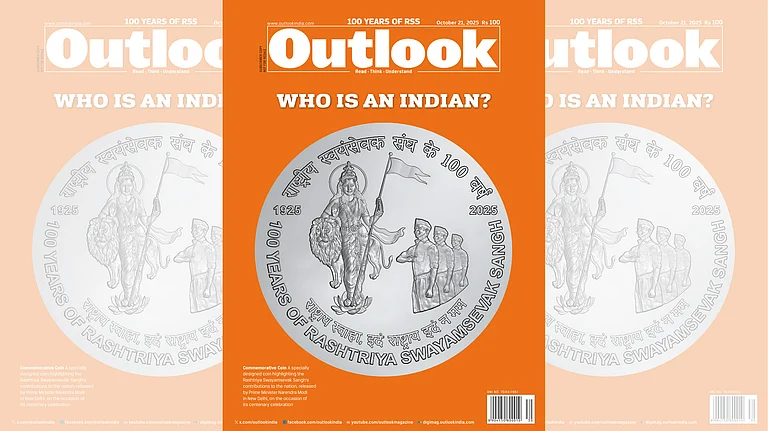

The RSS, a self-styled cultural organisation with a pan-India presence and a decade of power-sharing with the BJP, remains largely unknown to most people on the streets.

The intriguing part of the RSS’ practice is where paranoia and civility, fear and sense of belonging, and culture and violence seamlessly inhabit together.

They create problems of paranoia and provide the comfort in building new temples, and in bringing children from the Northeast to admit them in Vedic Pathshalas. In the absence of a friend in life, this looks like an assurance that does not pull you out of alienation.

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times,” the opening lines from Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities fits well with a similar epithet regarding the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). The RSS has changed immensely over the years but there is no visible change. The best possible way to capture the journey of 100 years for the RSS is this moebius kind of inside-out and outside-in. The RSS has changed, relentlessly contradicting, overturning and denying many of its past practices, but in essence there seems to be no change in its approach to politics and its vision of a cultural/religious majoritarian state.

Why does it claim the changes it does? But why are they then not the changes that they wish to project. If one can make sense of this mirage, one can approximate the means and methods of the RSS. One can also, perhaps, map the unprecedented rise of the RSS in the last 100 years—from the rugged margins of Indian society and politics to the centre stage of wielding power (without much of accountability). In order to understand these dilemmas, this special issue of Outlook does not recount the familiar history of the RSS, but attempts to bring to the readers a set of issues that found little attention in the public domain. The familiar issues of the role of the RSS or lack of it in the national movement, their reluctance to accept the national flag, their role in Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination or denial of it, among many such issues have been recounted multiple times. Also, the reach of the RSS today is growing for other reasons that some of these issues may not be able to account for, however important they may remain historically. And that is what has changed, or has it? The attempt is to wedge-open the space for a deeper understanding. There seems to be a liminal space of unchanging change.

The RSS, a self-proclaimed cultural organisation is sharing power with the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) for the last 10 years and has pan-India presence, but if you were to walk on the streets and ask common people about the RSS, I seriously doubt how many will know anything substantive or would have even remotely heard of it. It resembles the life of a pracharak (preacher), as we cover in some detail in this issue, who is active but anonymous. The RSS continues to remain a semi-secretive organisation. It is startling to observe in the days of libertarian consequentialism, and in times of death of utopia, the RSS continues to attract a committed cadre that may work and die an anonymous life. What is the motivational factor? Is it a genuine belief of working for a higher cause of region, religion and nation, or do the pracharak’s understand, at some level, that this is a power game at the end of the day? It is finally about gaining power and preserving it for the dominant sections of the society? How do rugged pragmatism and crude calculations co-exist with uncanny utopia and idealism? Is it not finally about a depraved worldview—a contest between the victor and the vanquished? It is like inviting respect on the basis of creating fear. Is it finally about fear or respect? Is it finally about the means without the end? The RSS provokes more questions than answers.

In one of my conversations with a relatively moderate young activist and full-time worker of the RSS, I was expressing my lament as to what have they done to India’s higher education. He not only readily agreed with me, but was also forthright in his own critique of the damage done. I went on to connect mediocrity and diffidence among the rightwing activists with the repeated violent eruptions, and organised mob-lynchings and other such stuff. A girl student went on to add how even festivals have become so regimented and militant among the Hindus that there is no festivity left, especially for the women. To this he vigorously disagreed with the student and supported the militant character and argued that every Hindu needs to become militant to protect their women from the Muslims. He said there will be a time when Muslims from the outside will attack India in a big number, when police and even the army cannot do much, and it will have to be every Hindu to defend, and that is what the Sangh prepares you for. This is a phenomenon of the dominant feeling vulnerable. It is the powerful feeling helpless and persecuted. Is it because they don’t come to terms with changes that come with time or the nature of social change that has come which has brought with it a toxicity that is all so pervasive that there is no effective distinction, on this account, between the hegemone and the subaltern. Both the dominant and the dominated are indifferent and toxic, it’s only a matter of gradation as to who wields the power to realise better. Is the rise of the RSS a symptom of collective failure? A failure to pay heed to Gandhi’s tireless caution not to abdicate the ideals of co-responsibility in our search for dignity and equality. Gandhi, in fact, thought there could be no equality without co-responsibility. The RSS has only replaced equality with samrastha (social harmony), and co-responsibility with kartavya (duty).

Gandhi was relentless in trying to teach us the art of co-responsibility because he could clearly see that without it any change, in fact, remains unchanged. Is the same un-change that we are witnessing today in the 100 year journey of the RSS? If change does not bring greater solidarity, civility and mutuality, is it any change at all? Is the RSS not a representation of this nihilistic morbidity? Is it not the reason why Gandhi is abused and Nehru subjected to visceral rejection because what they stood for looks so alien? It looks like they wanted us to slow down, when we needed pace; they talked of love, when we needed explosion of animal spirits. Is the terminal decline of the Congress because it continues to claim to be guided by Gandhi, but had their former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh speak of animal spirits? The RSS, on the other hand, glorified animal spirits and desecrates Gandhi, which comes across as much more authentic, organic and palatable. They did not hesitate to construct a temple for Nathuram Godse. Has the spirit of Godse and animal spirits come to represent the anxiety of the middle classes and the aspirations of the ‘depressed classes’?

Paranoia and Civility

This then is the intriguing part of the RSS’ practice where paranoia and civility, fear and sense of belonging, and culture and violence seamlessly inhabit together. A sense of home is the abode of insecurities. A sense of cultural continuity provokes disruptive and destructive eruptions and erasures. Unless we make sense of what is bringing to life this uncanny combinatory practices together and what meaning do they make in the larger lifeworld of the common people, we will not know the unchanging essence of the RSS. Is it this disruptive combination that is at the heart of the rise of the RSS in the last 100 years? Does it also explain the relative decline of parties such as the Congress, born from the anti-colonial utopia?

It is the complex matrix of cultural symbolism and social psychology that people are responding to. They signify the changing times, yet the RSS manages to implant its age-old agenda into the changing times. Indian democracy, among many other factors, succeeded because the Congress Partly genuinely and relatively respected the idea of freedom, but was also so disorganised and decentered that democracy and freedom became default templates. It is this disorganised nature that has allowed for new spaces to be created and allowed for social mobility of the disadvantaged castes. It was the best display of Gandhi as an anarchist. Today, that freedom is beginning to feel like indifference. Freedom comes with distance. Author Robert B. Talisse in his recent book, Civic Solitude: Why Democracy Needs Distance, argues that, “I will argue that a certain kind of solitude is necessary for good citizenship. Maybe democracy isn’t found in the streets after all”. To maintain freedom, people will require to step back to not convert differences into enmity.

The RSS has relentlessly followed exactly the opposite idea of personalising democracy. It culturalised economy and Hinduised welfare. It brought in an everyday lingo into governance through the BJP. From suggestions on how to face stress during exams to what temperature we need our air conditioners to operate at so as to not fall sick. The National Education Policy (NEP) attends to growing mental health issues and has also proposed a course on how to face break-ups and other emotional issues. From democracy’s pursuit of just life, the shift is towards a good life. The shift is from civic solitude to intrusively personalised democracy. Faceless anonymity of modern life already delivers freedom as indifference, what we are now moving to is personalised appeal that is illiberal—but whoever believed there are easy options out there? Narendra Modi and Yogi Adityanath are what I call ‘intimate strongmen’. It is the ethos of the RSS that could create a new model of governance.

A recent post on Facebook that I came across summed it all up for me when somebody said it feels pretty lonely when you are alone, and very annoying when you are with friends. This is what it has come to, an anxious choice between feeling biting loneliness and toxic friendships. There is no home or community to hide behind. We are open to the elements with violence as everyday interactions. New kind of assertions for recognition are enriching life experiences less and adding to anxious uncertainty. Or to frame it another way, the toxic domination that some faced in society in the past is pretty much the reality for all today. From the injustice of inequality we have moved to injury of equality. What kind of a change is it? Is it a change at all?

The RSS, as a cultural organisation, does not resolve the problem; it only acquaints you better with the situation. Reality becomes more convincing and the RSS only offers a narrative of imaginary comfort, even as they watch the crisis deepen. They will swing between nostalgia and nihilism. They create problems of paranoia and provide the comfort in building new temples, and in bringing children from the Northeast to admit them in Vedic Pathshalas. In the absence of a friend in life, this looks like an assurance that does not pull you out of alienation. Alienation becomes a condition, assurance a symptom. Meanwhile, Seva Bharti and Vanvasi Kalyan Ashram continue to distribute free ration, offer health services, and create schools in slums and for tribals. Pracharaks voluntarily look after the old whose children are part of jingoistic rallies in the US. A lonely old man in my colony once told me that 112—the dial number of the police and the emergency number to call the ambulance—are his only best friends today. It shook me up so much that I ensured feeding the number of the ambulance of the nearest hospital around in my newly-acquired android phone.

Is There a Future for the RSS?

As we are analysing the past 100 years of the RSS, we cannot make sense of it without making sense of the place of the RSS in the coming years. The quest to answer this hypothetical question will lend clarity to understand the past. The future will lend us a frame to understand the past. It is undeniable that the RSS has gained unprecedented centrality in the political and also social affairs of the nation. In fact, the RSS believes in building and making a society, not a state; in desh chalana hai, sarkar nahi (we need to manage the nation, not just a government). It has expansive plans based on its knowledge of the past, but the future of the past is changing in unknown ways. The RSS in unapologetic about preserving family and building a society, unlike other modern visions that begin with the state and end with the economy. In classical terms, it’s often called as the political economy method. This, however, coincides with the larger changes in the methods of managing global capitalism. It is, therefore, always worth asking in assessing the future of the RSS, if it’s unconsciously riding a moment or consciously building a momentum. I don’t think the RSS itself has made complete sense of this.

The RSS remains a semi-secretive organisation. It is startling to observe in the days of libertarian consequentialism, and in times of death of utopia, the RSS continues to attract a committed cadre that may work and die an anonymous life.

Israeli behavioural economist Daniel Kahneman, who won the Noble Prize, has also argued how humans are not exclusively rational beings. In his book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, he says, “Social scientists in the 1970s broadly accepted two ideas about human nature. First, people are generally rational, and their thinking is normally sound. Second, emotions such as fear, affection, and hatred explain most of the occasions on which people depart from rationality. Our article challenged both assumptions without discussing them directly. We documented systematic errors in the thinking of normal people, and we traced these errors to the design of the machinery of cognition rather than to the corruption of thought by emotion.” He brought in the place of intuition in everyday decision-making. We need to understand social psyche and individual psychological traits to even make sense of human economic decisions and transactions. It brings back, common sense, just the template populists ride on from Donald Trump, Giorgia Meloni to Narendra Modi. We are witnessing a global common sense revolution—‘Its common sense, you stupid’!

In not aligning with intellectually derived ideas, when societies change rapidly, those with anti-intellectualism have the default benefit as they don’t try to hang themselves to obsolete frames. There not having a frame comes across as both radical and democratic. It almost looks accommodative, till such time when common sense begins to pale and paranoia takes over. Paranoia seems to have gripped the rulers about Gen Z after the events in Bangladesh, Nepal, and now Ladakh in India. Can the common sense of the past, understand the Gen Z of the future. Will the RSS attract the attention and admiration of the Gen Z? Khaki shorts may have given way to Khaki pants, but the lathi continues to wield.

There is hardly a household of family and friends I visit these days who are not deeply worried about their kids. Either they are exasperated or struggling to make basic sense of this younger generation. They look indifferent but self-sufficient, emotionally broke but wanting to be independent, they may look irreverent but less toxic. They look alienated but they are certainly less prejudiced. It therefore comes as a surprise that such an inward-looking and spaced out generation can suddenly occupy the streets.

I was once invited to a college as a guest speaker. The student who came to pick me up was with the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP). I asked him—to make an otherwise anodyne conversation interesting—tell me one thing you don’t like about your organisation and he did not hesitate to say, the way they look at and treat the girls. This is what change looks like. It did not take him an extra effort to overcome gendered prejudice; it came to him more naturally. Gen Z may be self-absorbed and unrealistically aspirational, but they also carry less baggage and the way they will look for change—social and political—will also be novel and in unknown ways. Can the RSS hop and pop? An organisation that takes pride in being rock solid in times of liquid modernity, can it catch up with the change? Or, will it continue with the business-as-usual of continuing with its unchanging change? The following pages will give you a glimpse to make up your mind.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Ajay Gudavarthy is with the centre for political studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.