Summary of this article

India is moving to curb children’s screen use, proposing social media bans while pushing newspapers back into classrooms.

Educators warn bans aren’t enough, stressing that reading habits and attention can’t be rebuilt without libraries and guidance.

The deeper crisis is attention; regulation alone can't fix it.

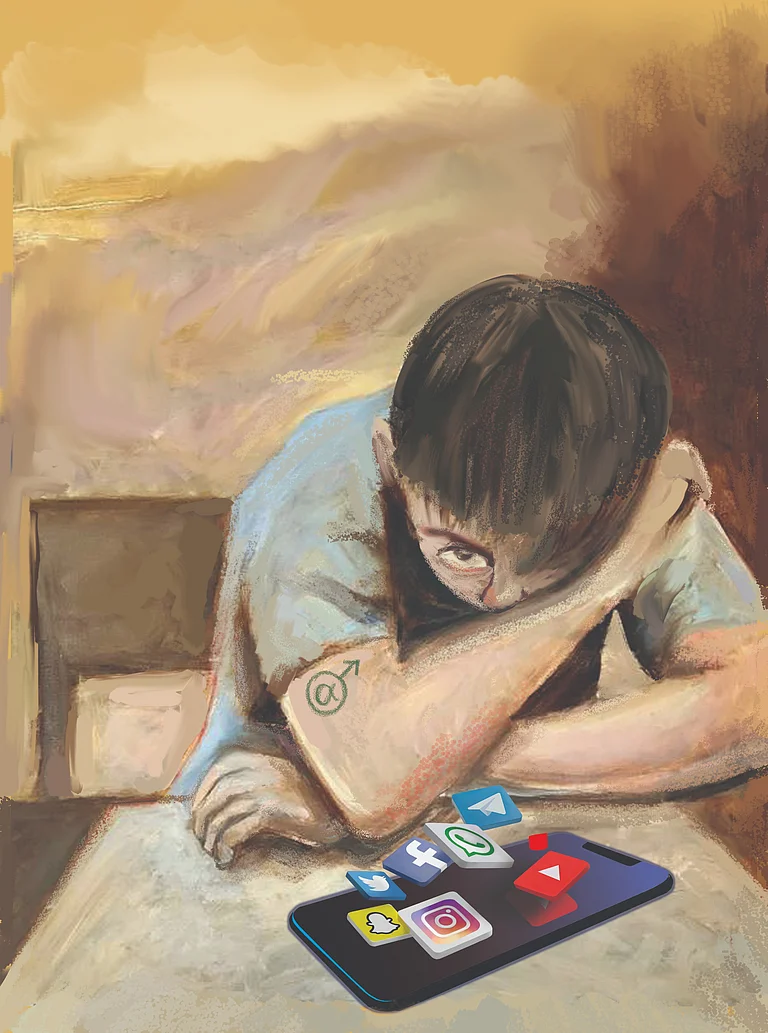

The debate around children’s engagement with media is intensifying in India, with institutions increasingly stepping in to shape how young people consume information. Earlier this month, the Madras High Court floated the idea of an Australia-style ban on social media platforms such as Instagram, Facebook and Snapchat for children under 16, citing growing concerns around mental health, attention spans and online safety. The court was hearing a petition which raised concerns how pornographic content is easily accessible to children.

Almost simultaneously, the Uttar Pradesh government made newspaper reading mandatory in government schools, positioning print media as a corrective to declining reading habits and shrinking attention among students.

At Akshara High School, Mumbai, similar reading sessions already exist, says Mridula Chakraborty, Founder Trustee, who describes weekly assemblies where students discuss what caught their attention in the newspaper. The exercise, she says, is less about controlling information and more about helping students understand how issues are reported and framed. “In today's world, we cannot shield children from information that is freely available- also newspapers are an opening point about how journalists report a particular subject/ topic and it is extremely important for young adults to decipher and form their opinions on how they see it,” she says.

Taken together, these moves signal a larger anxiety: that algorithm-driven platforms are overwhelming young minds, while slower, deliberative forms of engagement—like reading newspapers and books—are being edged out. Educators, publishers and literacy advocates argue that this moment is less about nostalgia for print and more about cognitive survival: how children learn to focus, interpret information, and form independent opinions in an always-on digital ecosystem.

Yet, as the conversations around a social media ban gather momentum, there is pushback against the idea that restriction alone can fix what is essentially a structural problem. As educators point out, children cannot be fully shielded from information in an era of ubiquitous access; what matters more is teaching them how to read, question and contextualise it.

Newspaper-reading sessions in schools, for instance, are being seen not just as a literacy exercise but as an entry point into understanding how news is reported, framed and debated—skills that are increasingly critical for young adults navigating both print and digital worlds

While keeping phones out of schools is showing early promise, says Michael Creighton, a full-time curriculum advisor with The Community Library Project, newspaper reading alone cannot substitute for sustained access to varied and interesting texts. Proficiency, he notes, comes from practice — and from allowing students to choose what they read. “There is a lot of research that shows that becoming a proficient reader requires practice in reading a wide variety of text. Ideally, that text should also be interesting and relevant to students! Giving students meaningful access to their choice of reading materials in classroom, school and community libraries really needs to be a priority,” says Creighton.

“Sure, there is a growing consensus among researchers and educators who have studied these issues that social media, especially when delivered from smart phones, is unhealthy for children,” he adds. While age restrictions on social media may reduce mental clutter, it is clear that bans without parallel investment in libraries, reading spaces and teacher-led engagement risk becoming symbolic gestures. The challenge, is not merely to take screens away, but to replace them with meaningful, accessible alternatives that make sustained reading—and thinking—possible again

Co-founder publisher of Karadi Tales, Shobha Vishwanath feels the problem is not a loss of interest in books but a loss of attention itself. “I see the toll social media takes every single day. Kids aren't losing interest in books, it’s that their attention is being shredded by constant pings and scrolls. Honestly, it’s hard for a book to compete with an algorithm designed to never let you go," she says.

An age restriction might help clear some of that mental clutter, she believes, but it's not a silver bullet. “You can't just ban social media and expect a reading culture to sprout up overnight. That takes functional libraries, educators who have the time to care, and homes where reading is actually fun, not a chore. If we're going to talk about bans, we also need to talk about serious investment in the things that make reading possible in the first place,” adds Vishwanath

The renewed drive to restrict children’s access to social media and reintroduce newspapers into classrooms reflects a genuine concern about what constant connectivity is doing to young minds. However, children also benefit from it, because often it makes them feel belonged. 15 year-old Zoey D’Silva of Mumbai says, “I think social media can actually help children socialize; I know it helped me. I would say maybe prevent children from opening public Instagram accounts and add parental settings to control what children watch online. But entirely banning it for children is like depriving children of socializing and connecting with other kids.”

It is true that anxiety, distraction and emotional overload are no longer abstract fears; they are being felt daily by teachers, parents and publishers who work closely with children. But the answers being proposed -bans on platforms and mandated reading periods -risk oversimplifying a far more complex crisis.

What emerges instead from classrooms and libraries is a quieter truth: attention has to be cultivated; it cannot be legislated into existence. Children need spaces where reading is not performative, but pleasurable; where books and newspapers are available not as moral correctives but as invitations. Without sustained investment in libraries, trained educators and a culture that values slow thinking, even the most well-intentioned bans may only create a vacuum.

As India debates how much of the digital world children should be kept away from, the harder question remains unresolved: what are we willing to give them in return?