Summary of this article

Epstein files resurface cyclically, blending real crimes with media spectacle and public voyeurism.

Cultural works like novels and shows train us to consume trauma as narrative thrill and revelation.

Desensitization from repeated exposure hinders reform, urging focus on systemic prevention over scandal.

Each time the Epstein files reappear, they do so with the choreography of a premiere. They are loud, persistent, and appear to be revelatory, although you are wondering what’s new.

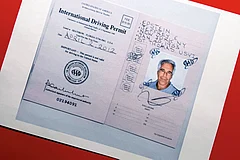

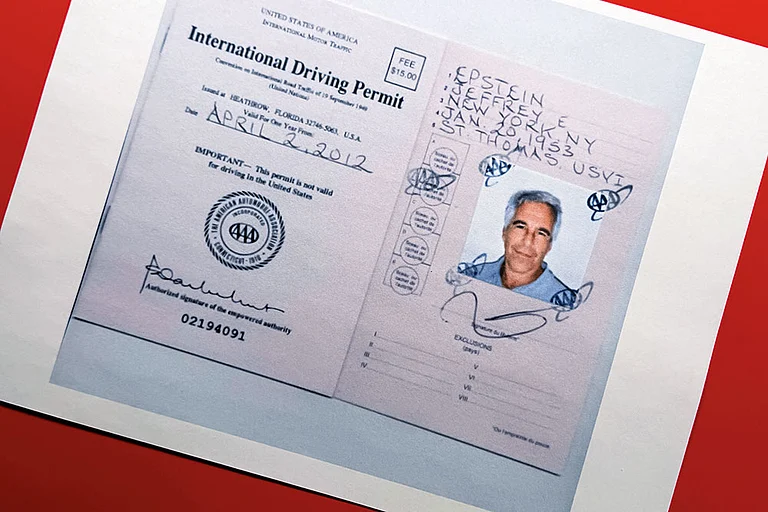

Jeffrey Epstein is dead. But the investigations around his network continue to ripple outward in fragments—court documents, depositions, redactions, speculation. As documents are unsealed (and pile up to the height of the Eiffel Tower, we are told), names begin to trend. The public rhythm is oddly familiar: a cyclical surge of attention whenever files are released or reinterpreted. The legal process inches forward, the spectacle gallops. Primetime tickers pulse with the words ‘explosive’ and ‘revealed’. Social media turns micro-forensic: flight logs are examined, associations mapped, timelines reconstructed, dots connected. There is outrage, disbelief, and a grim kind of satisfaction and smugness at the possibility that someone rich and powerful might finally be exposed.

And then, just as predictably, the cycle ebbs. Until the next release.

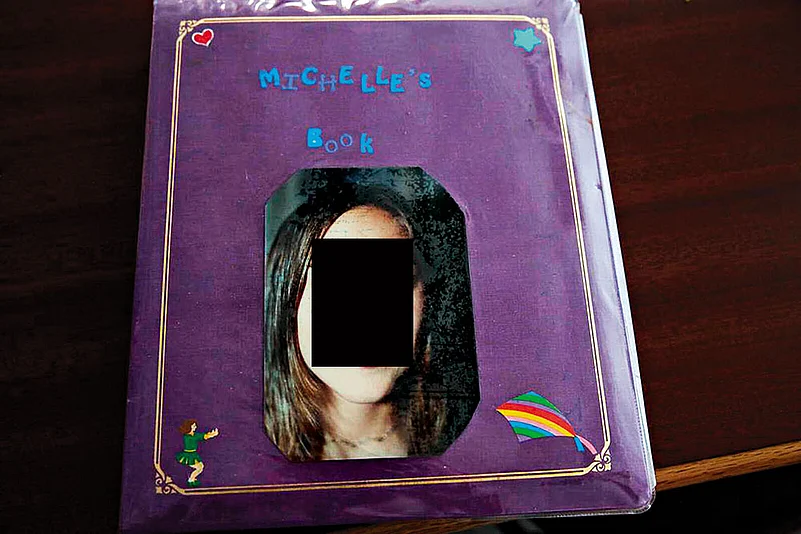

It feels necessary to begin with a disclaimer: the crimes were real. The survivors are real. The damage is of astounding proportions. Transparency and accountability are democratic necessities. But it is also true that something else hums beneath this repeated public frenzy—a familiarity, almost a fluency, in consuming trauma as revelation.

We have been trained for this kind of voyeurism.

In contemporary literature, extremity has often come to stand in for seriousness. Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life became shorthand for emotional devastation—a novel so relentless in its suffering that readers described feeling wrung out, yet compelled to continue. Pain was not incidental; it was structural.

On streaming platforms, harm frequently arrives in instalments. Netflix’s 13 Reasons Why blurred the line between awareness and aestheticisation, turning suicide and assault into cliff-hangers. Dahmer—Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story repackaged real murders into bingeable drama, prompting unease from victims’ families who felt history had been converted into entertainment. The series Making a Murderer structured a complicated legal saga as episodic suspense. Even The Lovely Bones placed sexual violence within a lyrical afterlife narrative, inviting readers to inhabit grief as story.

More recently, the Japanese writer Uketsu has captivated readers with puzzle-like tales in which ordinary domestic spaces conceal hidden brutality. The reader decodes drawings, floor plans, fragments—the revelation of buried violence becomes the reward. The reader cannot stop. None of these works are morally equivalent to the Epstein case. But they illuminate a cultural grammar we now inhabit. Trauma has become narrative propulsion. Hidden harm is the twist. Revelation is the payoff.

So when the Epstein files circulate, we approach them with the same literacy. We decode. We speculate. We search for the next name. The structure is familiar: concealment, disclosure, escalation.

“Traumatic stories have a universal appeal which transcends cultures across the world. They may connect at a certain level with the collective trauma our species has been through during its relatively brief presence on our planet as well as to our individual experiences,” says Dr Rajesh Parikh, Director of Medical Research and Hon. Neuropsychiatrist at Jaslok Hospital and Research Centre. “These stories of trauma and resilience are the stuff that constitutes great legends as well as contemporary narratives across multiple art forms such as cinema, drama, dance, painting and sculpture.”

In other words, our pull towards darkness is not new. What’s new is the scale and the speed.

“Given the nature of social media, awareness often descends into voyeurism. Presentation is almost always fine-tuned to get rapid and enduring engagement for commercial reasons. It is rapidly becoming the opium of our times. We are inherently a curious species. It is simultaneously our strength and weakness,” reminds Parikh.

The problem is not curiosity. It is what the ecosystem does with it.

Certain strands of media coverage of the Epstein files have leaned into the spectacle—foregrounding celebrity adjacency, reducing complex power structures into clickable lists, amplifying the salacious over the systemic. Who flew where and with whom? Who appeared in which log? Who received an invite to a party? Who might be implicated? What is it we don’t know about the people we think we know? The drama of recognition advances as we peel an infinite onion.

Psychologically, this incessant repetition, this overdose of Eiffel Tower-level information reshapes us, until we are numb. “This has been proven in controlled experiments as well,” Parikh notes, when asked whether repeated exposure can desensitise audiences. “In one study, children were exposed to either benign or violent content on television and thereafter given toys. The ones exposed to violence were destructive with their toys. Then there is the notorious Milgram experiment conducted at Yale University in the early 60’s which measured human ability to perpetuate Nazi-like trauma on innocent victims when instructed to do so by an authority figure. There are horrors being perpetrated across the world and to a large extent we are all being desensitised to them. On a brighter note, there are some whose sensitivity and conscience are not numbed and they remind us of our humane natures. For every Hitler there is a Mahatma.”

But desensitisation rarely announces itself. It is stealthily incremental. The first disclosure shocks; the fifth barely stirs. The language escalates—bombshell, explosive, damning—as though horror must now compete for attention. At the same time, outrage can feel purposeful. To express moral disgust publicly is to signal alignment. Of course we are human and have to pick a side. It creates the sensation of participation. But outrage, however sincere, is not the same as reform.

This brings us to the blurred line between witness and consumer. “The distinction is blurred. Evidently, being a direct witness is more powerful than consuming trauma vicariously. Then again, it is an issue of individual sensitivities. Some of us could get as affected by even reading about these traumatic events as we would be by directly witnessing them.”

We are all affected—sometimes deeply. And yet, there is always a screen between us and the harm. We feel intensely; we act minimally. We wait for the next shock, instead of asking what must shift.

If there is a more responsible way to engage, Parikh suggests it requires moving beyond the immediate drama of disclosure.

“One, perhaps, is to catalyse enquiry and analysis into what we are exposed to. In the context of the Epstein files, not just who was involved with him and what he unleashed but the deeper questions of a society that made it possible and the extent to which similar or even worse things are going on elsewhere in the world today and what we need to do as curative and preventive measures.”

That shift—from names to networks, from scandal to structure—is less thrilling. It does not trend. It debilitates. The phrase “trauma porn” is provocative and yet it gestures toward a discomforting truth: in the attention economy, suffering travels fast. It is sharp, morally charged, addictive. Repair is slow. Prevention is procedural. Systemic change rarely arrives with a soundtrack; it is never viral.

The Epstein files will surface again. They will horrify us again. We will scroll again.

The searching question is not whether we are curious—we always have been, as Parikh reminds us. It is whether we can resist treating each revelation as narrative climax, and instead sit with the harder, less cinematic work of asking how such harm was enabled—and what it would actually take to prevent its recurrence.

Watching is easy. Witnessing is not.

Lalita Iyer is an Associate Editor at Outlook and the author of Sridevi: Queen of Hearts, The Whole Shebang, Raising Mamma and other books

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

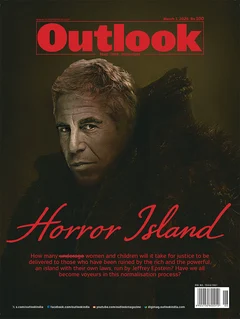

This article appeared in Outlook's March 01 issue titled Horror Island which focuses on how the rich and powerful are a law unto themselves and whether we the public are desensitised to the suffering of women. It asks the question whether we are really seeking justice or feeding a system that turns suffering into spectacle?

_(1).jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&format=webp&w=768&dpr=1.0)