Most girls picked by Epstein were from poor families who were offered cash to “massage” him at his villa

Others were lured with the promise of scholarships, art programmes and elite social access at his Upper East Side townhouse, where the abuse took place

In Eastern Europe, his links with modelling agencies were used to sell dreams of becoming Victoria’s Secret models before they were trafficked to the U.S.

(Trigger Warning: This story contains references to explicit content of a sensitive nature. Reader discretion is advised.)

Haley Robsen was 16-year-old when she first met Jeffrey Epstein. Coming from a family marked by emotional neglect, the absence of parental support pushed her to look for both care and financial stability elsewhere.

In 2002, as she was leaving school, a man accompanied by an underage girl stopped her and asked if she wanted to earn money by giving massages to a man after school. Unsure but persuaded by the promise of $200 for what she thought would be a one-time visit, she agreed.

Less than an hour later, Robsen arrived at Epstein’s mansion in Florida’s Palm Beach, a stretch often called “Billionaire’s Beach”, home to more than 58 billionaires, including high-profile residents such as Donald Trump. Inside the vast villa, the silence was unsettling, broken only by the sight of nude photographs and statues of children. “Initially I thought those were photos of his kids,” Robsen said, her younger self unable to grasp what she had walked into.

She was asked to wait in a room. Soon, Epstein, then 49, entered naked and told her to remove her clothes as he brought out adult toys, triggering memories of the sexual assault she had survived just a year earlier, when a 22-year-old man raped her. She had been lied to about Epstein’s profession and for the longest time, she knew that he was a scientist working with NASA.

“For hours, he forced me to do things to him sexually and kept on doing things to me sexually,” Robsen said, adding that when she told him she could not continue, he persisted.

"He finished masturbating and he said was extremely disappointed in me [for not allowing intercourse],” Robsen said, adding that the image of that moment does not escape her mind even today.

Women across the United States, the United Kingdom and the Virgin Islands have since accused Epstein of sexually abusing and trafficking them under the pretext of massage work or false promises of modelling opportunities, with some saying they had approached the FBI and local police as early as the 1990s but were not taken seriously.

Robsen, now 40, was one of more than 1,000 girls, some as young as 14, who were recruited into the international sex-trafficking ring to have sex with Epstein, his associate Ghislaine Maxwell and other powerful men. Six years after his death, hundreds of survivors have driven renewed public pressure to identify Epstein’s alleged accomplices and force the release of the US Department of Justice’s (DoJ) 3.5 million pages of investigative files that contain testimonies, emails, photos, and police reports, revealing the spider web of his abuse. While only a few dozen accusers had earlier spoken publicly for fear of retaliation and harm to their careers and families, more women are now coming forward in search of accountability and transparency.

With no family support and no one to confide in, Robsen continued doing what she was told in the hope of earning enough money to leave Palm Beach and escape the abuse. At the same time, she began to see Epstein as a friend, his soft tone, reassuring words and apparent concern making her feel he was, in some way, her “knight in shining armour.”

“I am heartbroken for that little girl [her younger self]. I’m heartbroken for the 16-year-old who thought she was being heard and seen—the whole time it was a facade and a tactic to groom me,” she said.

Procuring Children

For nearly three decades, Epstein refined a system to procure children and young women, but the targeting followed a chillingly consistent pattern: vulnerability. Most were girls from poor families, who were offered cash to “massage” him at his villa. Others were lured with the promise of scholarships, art programmes and elite social access at his Upper East Side townhouse, where the abuse took place. In Eastern Europe, his links with modelling agencies were used to sell dreams of becoming Victoria’s Secret models before they were trafficked to the United States.

Robsen fell into the first category. She grew up in what she describes as an “impoverished” household, her parents constantly working to make ends meet for her and her two older sisters. Their near-total absence left her in the care of siblings, one of whom had a history of drug use and subjected her to repeated, violent beatings. “I was living in a nightmare in my house where I was constantly being abused by my sister physically while my parents were aware of it,” she said, adding that she had effectively been abandoned as a child.

“Nobody protected me. I asked for help from several of my close people, but nobody really stepped in,” she said.

Before she met Epstein, Robsen was already carrying the trauma of parental abandonment and earlier sexual abuse, yet she remembers herself as largely well-adjusted, a horseback rider, a football player and a “social butterfly” who wanted to go to college and build a better future.

Afterwards, that life collapsed. She withdrew, stopped playing sports and slipped into depression. “I was using substances to cope. I was entering relationships where I was being domestically abused,” she said. She finished school, but barely, and became an exotic dancer at 18. “I needed an adult to see me, to listen to me and to believe me when I opened up about the sexual abuse that I’d experienced,” she said.

In the midst of this, Epstein continued to reappear in her life, and in those moments, she said, he “felt human”.

“He would sit with me and ask me about my family, rape, money problems,” she said, explaining that he presented himself as someone who would help her escape her circumstances, something no adult had ever offered before. Robsen was vulnerable and Epstein was predatory; for him she was his perfect prey. “Part of Jeffrey's grooming tactic was that he showed signs of care and love. He would call me a good girl or say that I did a good job.”

The reassurance was always conditional. He reminded her she had been brought to his house for him and was supposed to make him happy “at all costs”. What followed became, in her words, their “little secret”, one she was forbidden to speak about.

“If I brought him a girl that he didn’t like or who didn’t look quite young, he would reprimand me. He would yell at me and he would tell me like, ‘I told you I like young girls',” she said, adding that sometimes, the complaints would be about the skin tone of girls being "too dark".

She said that experiencing such trauma in the public eye deepened her distrust of people as she grew into a young girl who could never be sure of others’ intentions or whether they had their own agenda, while her childhood deprivation of care made her accept any form of love in later relationships.

As a result, she often entered romantic relationships overlooking red flags and seeing partners through “rose-coloured glasses,” which eroded her ability to trust and left her without a healthy understanding of intimacy or sexual relationships. “You're willing to accept any form of love because you've never had it,” she said.

Kathryn Stamoulis, a licensed mental health counsellor in New York who specialises in adolescent psychology and has been working with several of the Epstein survivors, said grooming begins with the deliberate identification of vulnerability. Epstein, she explained, was “skilled at finding people’s unmet needs and exploiting them,” seeking out adolescents who were financially insecure, emotionally isolated, eager for opportunity or lacking protective oversight.

She said that vulnerability, “doesn’t mean weakness; it can include ambition… or simply wanting to feel seen and valued,” and he would assess who was least likely to be believed or most likely to remain silent. When victims tried to speak out or leave, they were often met with threats, financial, reputational or physical, reinforcing secrecy and dependency.

She added that Epstein’s immense power and status created a psychological barrier for victims through what is known as authority bias. “Most of us are socialised at a young age to follow the direction of adults and other authority figures and to believe that they ‘know better,’” she said, adding that when even powerful adults in his orbit complied with him, “you can see how it would be impossible for an adolescent to be able to navigate and escape this.”

‘The Molestation Pyramid Scheme’

Robsen was given an ultimatum: bring other girls to him or the abuse would continue. Over the next two years, she complied. There were days she missed school to take girls to Epstein. During that period, she was coerced into recruiting eight underage girls, the youngest just 14. The age of consent in the United States varies by state; in Florida, it is 18, making Robsen and the girls she recruited legally minors at the time.

At times, she said, she would receive sudden calls from Epstein’s assistant instructing her to bring a friend to the mansion or “she would be raped”. She continued doing as she was told.

Robsen is among the survivors featured in the 2020 Netflix documentary series Jeffrey Epstein: Filthy Rich. In it, she speaks about the burden of recruiting other girls and the guilt she carried for years. “I have been putting the blame on myself for too long. I kept bashing myself… But he was the adult,” she said.

The series describes what investigators came to understand as a “Molestation Pyramid Scheme”—a system in which survivors, some as young as 14, were forced to recruit other girls, creating an expanding web of abuse that stunned Florida police during the investigation.

Michael Reiter, former police chief of the Palm Beach Police Department, explained in the series that the pattern was consistent: girls were initially asked to give Epstein a massage; sexual abuse would follow; and they would then be told to bring in more girls. “Cases began multiplying,” he said.

Explaining the “pyramid”, Stamoulis, the psychologist, who dealt with several survivors said one of Epstein’s most calculated tactics was using teenage girls to recruit other girls. She said that using peer recruitment purposes would often result in disarming the victim and normalising the situation.

Court documents show that young women were asked to approach potential victims with offers of money in exchange for giving Epstein a massage. Although many girls initially felt the proposal sounded suspicious, seeing peers their own age participate made it appear legitimate, she said, “Having girls recruit other girls also made them complicit in the abuse of others, thus making it harder for them to get away,” she said, adding that many feared they would get into trouble themselves if they went to the authorities.

Who Controls the Narrative?

Soon after the release, the DOJ removed thousands of documents related to Epstein after lawyers flagged unredacted names and nude photographs, a move critics called one of the worst breaches of survivors’ privacy in U.S. history.

Mithilesh Priyadarshi of Jawaharlal Nehru University said that the bulk release of documents created only an illusion of transparency. “Dumping an enormous number of files at once often works as a way of suppressing news rather than revealing it,” he said.

Highlighting the media investigations and reportage, he added that many survivors were described as “women” or “underage women,” and that “the names of the victims were widely publicised” while abusers were not foregrounded. The debate he said became politicised, “everyone highlighted only the aspect that suited their narrative”, and, in the end, “the greatest loss was that of the victims.”

Such long legal battles, along with excessive media investigations and public scrutiny, have resulted in deeply retraumatising survivors, said Stamoulis. She said that the recent release of files by the U.S. Department of Justice caused renewed harm. “Publicly naming survivors while concealing perpetrators signals that their identity is less deserving of protection than the abuser’s,” she said, warning that sudden exposure can trigger anxiety, depression and hypervigilance.

“When institutions protect powerful people and expose survivors, it reinforces helplessness and teaches that silence is safer than seeking help,” she said.

Mishi Chaudhary, a US-based tech lawyer and the founder of Software Freedom Law Center, India (SFLC.in), said that in a case like this, the choice of full disclosure of identity should have been in the hands of the survivors.

“Survivors need the freedom to speak, to be believed, and to participate in the process without being stigmatised. Compensation and reparations matter because they impose a real cost on perpetrators,” she said.

The Long Road to Recovery

Laurie Marsden, a New York–based licensed clinical social worker who is herself a survivor of sexual abuse and now works with other survivors, said children are conditioned from birth to navigate unequal power structures.

“You could say children are born into extreme power imbalances,” she explained, noting that their complete dependence on caregivers for food, warmth and safety makes them highly attuned to authority and approval,” she said, adding that as children grow up, they quickly learn to read wealth, status and social privilege as markers of who must be pleased and obeyed, which “makes them the perfect victims.”

Because sexual abuse often begins gradually, many children do not recognise what is happening, she said. “They tell me they love me but are hurting me—the brain struggles to make sense of that duplicity,” she said, adding that this confusion frequently delays disclosure.

In high-profile cases, repeatedly recounting the abuse to the media, lawyers and prosecutors can be both liberating and deeply retraumatising. Survivors, she said, may experience intense physical responses, “they get nervous, sweaty, their mouth goes dry and they feel the original pain and anxiety even years later”, and those with PTSD can feel as if they are reliving the event.

Sustained, organised abuse can fundamentally alter a survivor’s sense of self and safety. “It can leave them feeling like the entire world is untrustworthy, like something is wrong with them, that they are to blame or broken,” Marsden said. In her clinical experience, those abused “the earliest and the longest have the least favourable outcomes,” while survivors abused later in life and for shorter periods often have better chances of recovery.

On healing, Stamoulis emphasised that recovery is deeply individual. Ongoing therapy with a trusted professional can help address anxiety, depression or substance abuse, but some survivors may choose not to centre their lives around the trauma, and that, she said, is valid. Others may find purpose in advocacy, though “it isn’t a victim’s responsibility to do so if it doesn’t feel right.”

She stressed that the survivors she has worked with were groomed and believed they were in a relationship with Epstein. “I don’t find the term to be minimizing. It’s a psychological process that helps a predator reduce the risk of victim disclosure, ensuring more access to that victim,” she said, calling it “complex and extremely psychologically damaging.” She added that while it is reported he abused about a thousand girls, no one can claim to know all the tactics he used.

Robsen, meanwhile, has continued being in therapy for at least eight years now and she believes she has a long way to go. Robsen called child sexual abuse a “global pandemic,” urging survivors to know they are not alone and not to blame, while warning that her fear now extends to children everywhere in what she sees as a climate of limited accountability. “I’m scared every day for all the kids in the world… the message they’re sending to the youth is that they’re not going to be seen, they’re not going to be heard, they’re not going to be believed,” she said.

As a mother of a 12-year-old girl, Robsen says her approach to parenting is deeply shaped by her trauma, for which she believes healing is necessary. Robsen is protective of her daughter while striving to give her the emotional security she never had, stressing that vulnerability stems less from poverty than from emotional neglect.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

“All it takes is for you to neglect your child and a perpetrator has now found a way in,” she said. “Please understand that not all love comes with good intentions… sometimes salt looks like sugar and the devil never comes as the devil.”

(Zenaira Bakhsh is an Assistant Editor at Outlook, where she covers governance, minority rights, gender and conflict.)

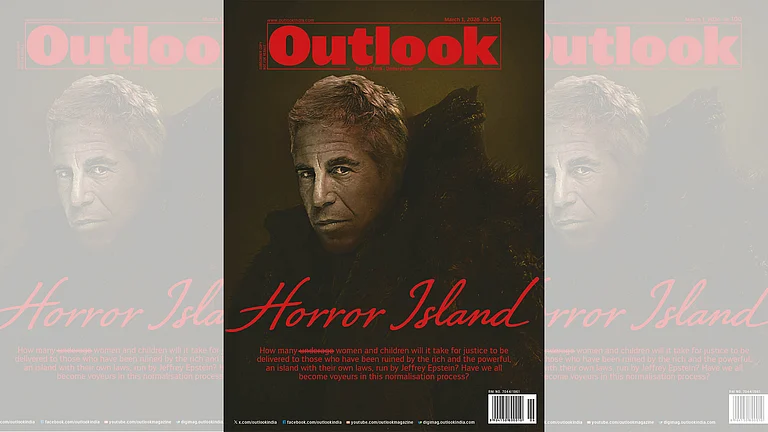

(This article appeared in Outlook's March 01 issue titled Horror Island which focuses on how the rich and powerful are a law unto themselves and whether we the public are desensitised to the suffering of women. It asks the question whether we are really seeking justice or feeding a system that turns suffering into spectacle?)