Summary of this article

The resurfacing of the Jeffrey Epstein files highlights how wealth, and proximity to power shielded perpetrators from accountability.

Repeated disclosures risk turning survivors’ suffering into consumable content, fostering desensitisation rather than justice or reform.

From legal loopholes to media constraints, the case exposes institutions that prioritised self-protection over safeguarding vulnerable women and children.

How many women and children will it take for justice to be delivered to those ruined by the rich and powerful? How much more should women endure when men in power walk away unscathed from the consequences of their unscrupulous and abusive actions?

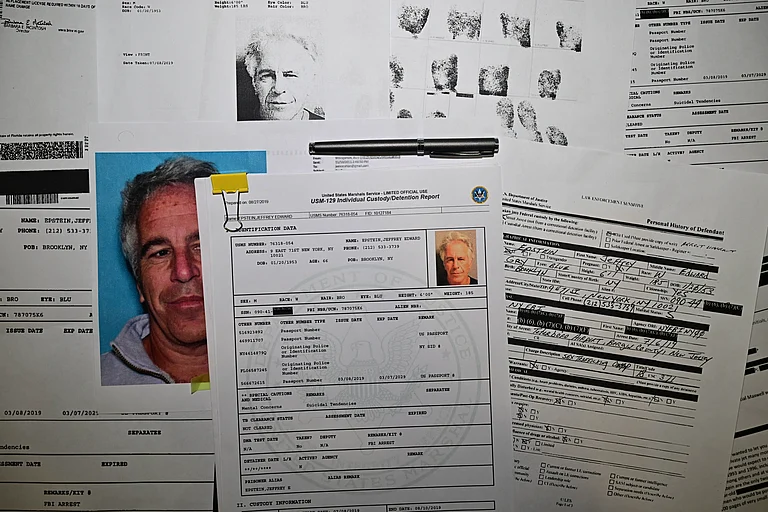

In January, a newly released cache of roughly three million files linked to the financier and convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein shed further light on his network, his relationships with elites, and the failures of federal investigations into his crimes. The disclosure followed US legislation passed in November requiring the release of all Epstein-related records.

The documents deepen concerns about a system that enabled the exploitation of girls, revealing how power and privilege can shield wrongdoing. Among those named are former presidents Bill Clinton and Donald Trump, former New Mexico governor Bill Richardson, former Maine senator George Mitchell, and Harvard professor and lawyer Alan Dershowitz, among others.

Being named, or having social contact with Epstein, does not in itself imply criminal conduct. However, the material raises serious questions about who knew what and when.

In sworn testimony, alleged victim Sarah Ransome said Epstein openly discussed trafficking girls to visitors at his New York residence and private island in the US Virgin Islands. Other alleged victims argue that prominent figures who associated with him must have been aware of the abuse, even if they did not participate directly.

One survivor, Virginia Giuffre, stated in a 2016 deposition that anyone who entered Epstein’s home and maintained a relationship with him would have understood what was happening.

Epstein’s 2008 non-prosecution agreement, reducing potential charges from sex trafficking of minors to soliciting prostitution, illustrated how money and influence can distort justice. He exploited a system he knew would protect him.

His associate, Ghislaine Maxwell, is now serving a 20-year sentence for what US attorney Damian Williams described as “heinous crimes against children”. For many survivors, her conviction underscores a painful truth: accountability remains rare, and justice long overdue.

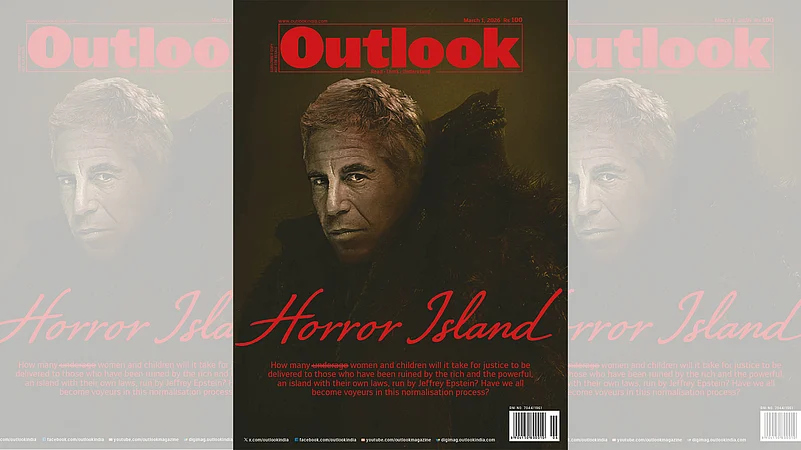

In the March 1 issue titled The Horror Island, Outlook looks at how the rich and powerful are a law unto themselves. It looks at whether all of us have become voyeuristic participants in the normalisation of such crimes.

Publisher and author Urvashi Butalia writes that how much ever women think they have gained in terms of rights, dignity and equality, in the minds of men, women are just commodities to used and discarded. The younger, the better.

Sex with minor girls is horrifying enough, but not for the Epstein network—the victims must be passed around, trafficked across some of the most formidable networks of power, money, prestige and influence that straddle the Western world, writes novelist and critic Saikat Majumdar in Writing with Fire.

As the Epstein files resurface, are we seeking justice or feeding a system that turns suffering into spectacle? asks Lalita Iyer in The Algorithm of Trauma. She writes that desensitisation rarely announces itself. It is stealthily incremental. The first disclosure shocks; the fifth barely stirs.

Mohammad Ali in A Page One Silence writes that the response to the Epstein files and their importance has been filtered through a media ecosystem constrained by legal risk, economic fragility and proximity to power. It is about the structural limitation of scrutiny where influence outlasts a scandal.

For nearly three decades, Epstein refined a system to procure children and young women, but the targeting followed a chillingly consistent pattern: vulnerability. All these women were poor. Zenaira Bakhsh looks at how Epstein operated his ‘molestation pyramid scheme’.

Snigdhendu Bhattacharya and Anwiti Singh look at how the even celebrated linguist Noam Chomsky sympathised with Epstein. They look at his life and his associates.

The time is right to dissect the dynamics of the spiritual wellness industry and shine the light of accountability on the powerful figures who drive it, writes Vineetha Mokkil in Bad Karma, while focusing on new age spiritual guru and ‘consciousness expander’ Deepak Chopra.

Language is an important tool while reporting such incidents. Peggy Mohan in Words That Numb looks at how terms like ‘underage women’, ‘sex with a child’, or referring to girls as ‘women’ in the Epstein files—rationalising the sexualisation of young children— have begun to hit a nerve.

But at the end of it, what happens to these people? Will it only end in outrage and no change and ultimately forgotten?