Summary of this article

Survivors breaking anonymity reclaim their voice and challenge the space long occupied by the accused.

The Epstein case exposes a powerful, complicit system that enabled widespread abuse.

Real change requires men and institutions to confront silence, power, and accountability.

Last week, Asha Achy Joseph, a film-maker from Kerala who had filed a complaint of sexual assault against a powerful political figure and film director in Kerala, chose to come out of anonymity. In doing so, she made a strong point: “If the survivor remains anonymous,” she said, “the accused gets all the space.” Other survivors, she said, would come out similarly, as part of a campaign against the shame and silence that attaches to survivors.

Asha’s words echo the ongoing global conversation on sexual assault as more and more women choose to discard silence and demand to be heard. Perhaps the loudest voice here is that of Gisèle Pelicot, the French woman whose husband offered her inert body freely to strange men. In waiving her right to anonymity, Pelicot powerfully spoke against the culture that shames women for being victims of sexual assault, but she also made another important statement—that she had given herself the right to be happy.

Carrying the terrible knowledge of what has been done to them, and living with the silence that is imposed legally and socially, has made it not only difficult, but often virtually impossible for survivors to get on with their lives. Many who choose to speak out struggle with themselves to do so. Years ago, I spoke to Marrewa-Karwoski, a US-based research scholar and a survivor of sexual assault by a person she considered a friend and mentor. Holding on to her silence for months, she realised it was eating away at her from inside, turning her into someone she did not want to be. This was what led to her decision to speak. Here is what she said:

“I am fed up of being silent. Why should he get all the space? If people only hear his story, that is what they will believe.” What she was pointing to was this: if only one side of the story is told, and is continually repeated, it is eventually taken for truth. And if the other side is not told at all, it is assumed not to exist.

She went on to add, as Joseph did and as Pelicot has done, and as all the survivors who are now finally being able to articulate what was done to them at the hands of the Jeffrey Epstein empire are doing, that the silence with which survivors are forced to live in a society that refuses to acknowledge the widespread nature of the crime of sexual assault is hard to endure. It’s lonely and isolating. Speaking up helps and it also reaches out to others in similar situations, in turn helping them to feel less isolated.

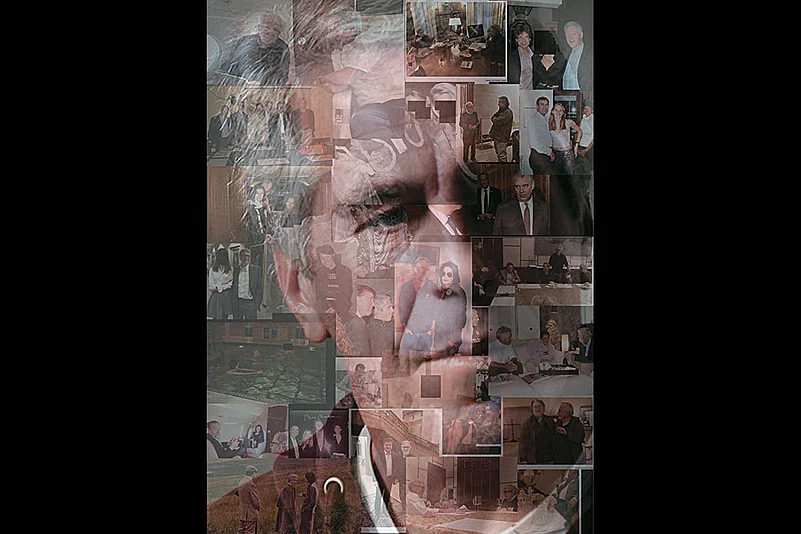

With so much noise about paedophilia in our cultures, how is it that this thoroughly morally corrupt system was allowed to continue?

Juliette Bryant was barely 20 when she was ensnared by the criminal circle created by Epstein. In Cape Town, where she lived, Bryant was ready to take the next step in her life and she began dreaming of a career. Epstein’s recruiters, women who worked with him (and who knows, they may themselves have been similarly ensnared) reached out to her, offered her a job in New York. Excited and hopeful, she agreed. Soon visas and tickets were arranged, but the flight that took off, ostensibly to New York, was actually headed to Epstein’s private island in the Caribbean. On the plane, she was seated next to the man who had been described to her as ‘the king of America’. He began assaulting her almost immediately.

In an interview, Bryant spoke of how bewildered and frightened she was. She did not know what was happening. The women who had recruited her watched and laughed at her plight. She did not know how to protest; she feared they would kill her. Silence was her only recourse. Fear and entrapment, and repeated sexual assaults became her life for many years. Barely out of her teens when it happened, it took her many more years to have the courage to speak up.

Bryant was not alone. As more survivors get to tell their stories, it is becoming clear that an increasing number of them were mere children, many of them in their teens. With so much noise about paedophilia in our cultures, how is it that this thoroughly morally corrupt system was allowed to continue? They were all part of it, the princes, the politicians, the corporate honchos who were all too willing to take a share of the ‘spoils’ (for that is clearly how they thought of the women in their minds), and indeed the academics and intellectuals who disparagingly spoke of ‘the hysteria that has developed about abuse of women’.

And it wasn’t only them. Clearly, there was an extensive and widespread network of recruiters. Then there were all those who participated perhaps because it was a job they had to do—the pilots, the hoteliers, the housekeepers, the security guards—but who could not have been unaware of what was going on. If the system hadn’t been complicit, if those in power hadn’t turned a blind eye to the happenings, perhaps something could have been done.

But the painful truth is something that story after story has revealed. No matter how much we think we have gained in terms of women’s equality and dignity, in the minds of men—the tinker, the tailor, the soldier, the spy, the corporate head, the Left-wing academic, the big politician, the small politician, the actor—women are just commodities to be used and discarded, and if you can catch them young, so much the better.

Deep in their hearts though—if they have hearts, that is—these men know well that women are not what they want them to be and that is why they need to drug them, to abduct them, to catch them when they are young, and to trap them in situations from which it is difficult, sometimes impossible, to escape.

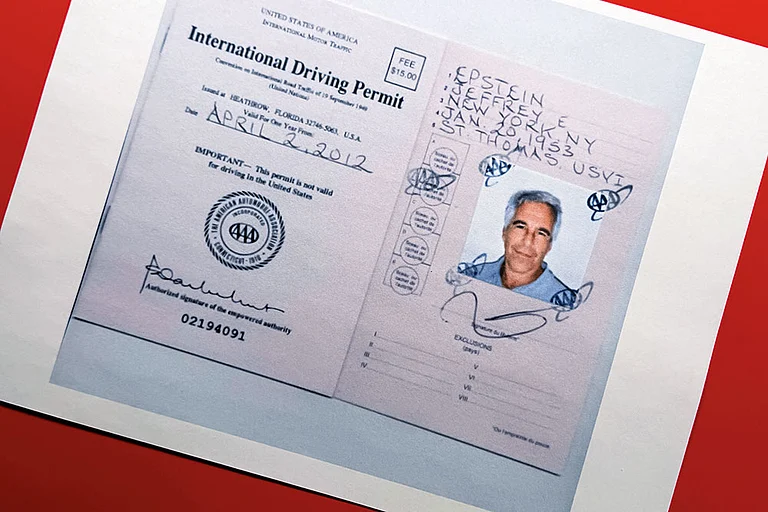

They also know, as Epstein did in 2008 when he managed to evade being convicted for sex trafficking of minors, that they can use their money and power to manipulate the system. When he signed a non-prosecution agreement that reduced his charges from sex trafficking to soliciting prostitution, he was playing a system he knew was complicit. And one he knew did not care for the survivors who were also probably too young to be concerned about. Thus, the prosecutors did not inform the victims of this agreement between the rich and the powerful.

As survivors speak out and tell their stories, it’s time, I think, for men to join the call for justice and respect, it’s time for men to speak up, to be cognisant of the power they hold and how the system helps them abuse it. If men choose silence in the face of this assault, there will, sadly, be no last man standing.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Urvashi Butalia is a feminist writer and director, Zubaan publishers

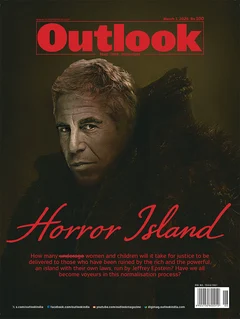

(This article appeared in Outlook's March 01 issue titled Horror Island which focuses on how the rich and powerful are a law unto themselves and whether we the public are desensitised to the suffering of women. It asks the question whether we are really seeking justice or feeding a system that turns suffering into spectacle? )