Testimonies describe how underage girls were groomed, abused, and pressured to recruit others, creating a pyramid-style network.

Despite Epstein’s death and Ghislaine Maxwell’s conviction, survivors argue that others who enabled or participated remain unaccountable.

Survivors are demanding full release of case files and disclosure of names, saying the truth cannot be buried with Epstein.

Standing in front of the Capitol Hill, on September 2025, Marina Lacerda broke her silence publicly for the first time about her sexual abuse at the hands of Jeffrey Epstein.

“After all these years, I was free,” she said.

Lacerda, also identified as “Minor Victim 1” in the 2019 federal investigation against Epstein, was only 14 years old when she was recruited by him in 2002. A friend suggested she could earn $300 giving a “massage” to a wealthy man.

“She made it sound so okay,” she recalls.

She had already been working since 13—factory jobs, waitressing, background modelling, office work. Survival had become her language.

“I was the head of household at 14,” Lacerda mentioned. “I just needed to make money.”

When she arrived at Epstein’s Manhattan mansion, she was overwhelmed. A big wooden door. A waiting room lined with photographs of powerful figures of politicians, royalty and the presidents. Upstairs, a hallway of black-and-white sketches of nude women. A massage room with lotions she recognised from Victoria’s Secret and others she didn’t.

She recounted how vividly she remembered the clouds painted on the ceiling.

“I remember looking at it, what a place to relax,” she says. “That’s how much of a child I was.”

What followed, Lacerda said, was nothing like what she had been promised. When her boundaries were pushed, she froze. She shook her head no. A friend told her not to be “uptight”. Epstein smiled and said she would “get comfortable eventually”.

“I remember thinking, this man is crazy. I’m never going to be comfortable with this.”

She left with $300. But bills were piling up, her mother wasn’t working, and when the call came again, she returned.

The second time, she says, he didn’t ask for anything at first. He was kind. Patient. Then, slowly, the lines blurred. One piece of clothing at a time. One step at a time.

“Before I knew it,” she said, “I was being raped and I didn’t even know how it got there.”

Years later when she began speaking to the other survivors, she realised something that stunned her. “They all said he raped them,” she recalled thinking. “And I said he never did that to us.” On the phone, one of the girls went quiet.

“What are you talking about?” she asked gently. “Marina, Jeffrey Epstein raped us.”

The words hung there. The other survivor reminded her how he would single her out, lift her, position her, force the others to watch. “This is how you do it. This is how a good girl is. Just like Marina.” And that’s when it came back.

Not forgotten, she says. Blocked. Buried. “I think that’s what trauma does to you.”

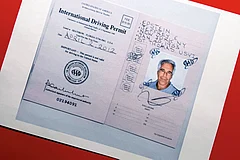

Lacerda was amongst many women who were sexually abused by Epstein when they were minors. Epstein was an American financier who sexually abused and exploited underage girls. In 2008, he pleaded guilty in Florida to procuring a minor for prostitution and soliciting prostitution, serving about 13 months under a controversial plea deal. Arrested again in July 2019 on federal sex trafficking charges involving minors in Florida and New York, he died in his Manhattan jail cell on August 10, 2019; his death was ruled a suicide by hanging.

“I was happy, I was sad, I was angry, I was confused. I was in shock. I cried.” For survivor Haley Robson, who was 16 when she says she was abused by Epstein, the news of his death triggered a flood of emotions. “I just froze. I sat there on my bed crying.”

“I think Jeffrey’s death was just the beginning. I do not believe he was solely responsible,” she added, arguing that Ghislaine Maxwell, Epstein’s long-term associate, played a central and driving role. Robson described Maxwell as “the head of the dragon,” alleging that she was the one “feeding” and enabling Epstein.

Maxwell was arrested in 2020 and convicted in 2021 of sex trafficking and related conspiracy charges for recruiting minor girls for Epstein. She was sentenced to 20 years in prison in 2022.

Just like Lacerda, Robson was called in for a “massage”, believing Epstein was a NASA scientist. She was 16. The first meeting began with questions about school and whether she was local to West Palm Beach quickly escalated to sexual abuse that lasted for an hour.

“During that hour of abuse, he brought out adult toys, which made me deeply uncomfortable,” she said. “He was disappointed in me afterward and gave me an ultimatum to bring him other girls or be sexually abused again.”

After which she got him at least eight girls.

Lacerda recalled how he preyed on her vulnerability. “I know you need the money. I know you’re going through a tough time. I know you’re not legal here in the States—and you need me,” she said he told her, urging her to bring him other girls if she wanted to keep earning.

Feeling lost and cornered, she complied. She does not remember how many girls she brought. “That’s how I entered the Epstein world,” she said.

He controlled nearly every aspect of their lives. He warned them not to drink or use drugs, threatening to test strands of their hair if he suspected they had. He discouraged them from using certain cab services because they kept records, a sign, she believes, that he was careful about leaving a trail.

He also manipulated them emotionally, pitting the girls against one another. He would praise one as “better” or compare how many girls each had recruited, turning exploitation into competition.

“It all seemed normal at the time,” she said. “We were children.”

Being an immigrant, Lacerda was not trafficked in the same way as some others but she alleged that she was also abused by Maxwell. One day, she said, Epstein unusually asked her and another girl to come to his bedroom, a space they rarely entered. A woman he introduced as a “friend” joined them; Lacerda later realised it was Maxwell.

They both raped us,” she said, adding that she does not remember many of the details—something she is glad about.

The abuse went on for nearly three years before Lacerda finally broke away. She said Epstein eventually let her go because she had become “too old” for him. “You’re not fun anymore. You don’t bring me age-appropriate girls,” she recalled him saying, pressuring her to recruit girls as young as 13 to 15.

Robson, too, left when she turned 18 in 2004. “I was scared, but I’d had enough,” she said. She moved out of the county despite fearing the consequences. “I realised I didn’t have to stay. I could leave and deal with whatever repercussions came my way.” Soon after, she said, her boyfriend was murdered in 2006.

The trauma, she said, followed her into adulthood. She entered an abusive relationship where she was physically assaulted while she was pregnant. “I had to call the police several times. It took me four years in the system to finally get my divorce,” she said. “I’m very lucky to have been one of the few who got away.”

Troubled Childhoods, Now Protective Mothers

Both Lacerda and Robson had their early years were marked by abuse and instability at home.

Lacerda said she was abused by her stepfather from the age of eight after moving from Brazil to New York to reunite with her mother. The abuse continued until she was 14. When her mother caught them, she screamed at him and told Lacerda it was wrong, but did not leave.

“When I would complain, she would yell at him, but nothing changed.After some time, he would even beat me up for telling my mom.” Lacerda said.

At times, she said, her mother would leave her alone in the house with her stepfather despite knowing what he was doing. She described how she would “literally cross her legs” and sit on a small ledge by the window, staring outside and thinking, "Mom, please come home. Why did you leave me?"

She added that some nights he would come into her bedroom, and she would lie there praying for “just one night” of quiet — “just peace.” All she wanted, she said, was to be left in peace.

She later went to the police herself, but alleges that nothing happened. Instead, she says officers intimidated her mother to the point that she downplayed what had occurred. When her grandmother arrived, Lacerda recalled, the focus shifted to questioning what she had told authorities, not what had been done to her.

Robson described growing up in what she calls a “nightmare —raped by an acquaintance when she was 15 and physically assaulted by her sister, while her parents, heavy drinkers, failed to intervene. “Nobody protected me. Nobody stepped in,” she said. After that abuse, she met Jeffrey Epstein, believing he would help her leave West Palm Beach. “Instead, he abused me.”

Today, both women are mothers to daughters—and fiercely protective. Their relationships with their families remain strained, with Robson completely cut off.

“I always tell parents: teach your children boundaries,” Lacerda said. “You don’t talk to me like that. You don’t touch me like that. You demand respect.” She limits sleepovers, monitors her daughter’s movements, and restricts phone access. “The internet is dangerous,” she said.

Robson follows similar rules, allowing sleepovers only with two trusted families and closely supervising her daughter’s digital life.

When she first became a mother, she said she had frequent nightmares. “In the beginning, I would wake up terrified, dreaming that Jeffrey was sneaking into my house to take my daughter from her bed.”

Motherhood, they say, is shaped by survival. “When you go through that kind of trauma, parenting is hard,” Robson said. “You want to give them the best childhood possible, without passing on your fear.”

Fight Still Continues

For nearly three decades, survivors of Epstein have refused to be silenced but initially they were neither heard nor believed, let alone get justice. One of the first to speak publicly was Virginia Roberts Giuffre, who in 2011 detailed how she was trafficked as a teenager by Epstein and his associate Maxwell.

Giuffre said she was forced to live as one of Epstein’s “sex slave” for years, coerced into sex not only by Epstein and Maxwell but also by powerful men from politics, business, academia and royalty. She described being treated as property, moved across countries, and silenced through intimidation. Eventually, she escaped and rebuilt her life in Australia. Her courage opened the floodgates for others. Many were encouraged to speak publicly and file complaints. In April 2025, she died by suicide at 21, a devastating reminder of how long trauma lingers.

Court records tell a chilling story. A November 4, 2010 deposition mentioned that Epstein “repeatedly sexually assaulted more than forty young girls” between 2002 and 2005 at his mansion in West Palm Beach, Florida, abusing many of them dozens, even hundreds of times”. The testimony described a calculated pyramid scheme: girls were paid $200–300 in cash to recruit other underage girls, expanding the network of exploitation.

Former Epstein employee Alfredo Rodriguez later provided investigators with a journal containing names of numerous young girls from across the United States and abroad, from Michigan and California to New York, New Mexico, West Palm Beach and Paris, underscoring the scale of the operation.

Long before Epstein’s 2019 arrest, women like Maria Farmer who complained about him to the FBI in 1996, her sister Annie Farmer, Sarah Ransome, and many others had tried to alert authorities. They endured smear campaigns, public shaming and relentless legal intimidation. Still, they persisted.

Even after Epstein’s death, justice feels unfinished. At press conferences on Capitol Hill, survivors have stood together demanding that the Department of Justice release all files and disclose the names of alleged perpetrators. Some have begun compiling their own records, determined that the truth will not be buried with him.

“It’s been years, but it’s not easy for the women to move on,” survivor Lisa Phillips said at one such gathering. “It’s not over until we say it’s over.”

Lacerda echoed that call. “We need to put all these men who have been brought to light. We know about these perpetrators. We need to bring them to justice. They need to see their day in court.”

For the survivors, this was never just about one man. It was about a system that enabled him. And the fight, they insist, is far from over.

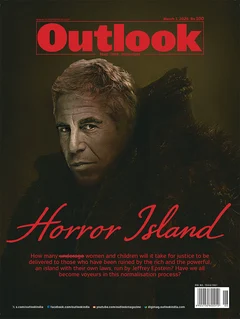

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Mrinalini Dhyani is a senior correspondent at Outlook. She covers governance, health, gender and conflict, with a strong emphasis on lived realities behind policy debates.

(This article appeared in Outlook's March 01 issue titled Horror Island which focuses on how the rich and powerful are a law unto themselves and whether we the public are desensitised to the suffering of women. It asks the question whether we are really seeking justice or feeding a system that turns suffering into spectacle?)