“Timeless” is one of the clichés used often to describe Rabindranath Tagore. Like most clichés, it holds much truth. But every serious reader of Tagore experiences the guilt of emotional anachronism, of loving something they know they cannot love anymore. My most recent jolt came from the experience of translating the short story, Shubhodrishti, ‘The First Look’, in my English version, for the forthcoming Oxford World’s Classics edition of Tagore’s stories. In this story, a wealthy man who is at least in his mid-20s, possibly older, stares at a local girl in a village where he is ravaging the peace with his hunting expedition. She is barely out of girlhood.

“One couldn’t quite tell her age. Her body had bloomed but her face looked young, as if nothing of this world had touched her yet. She seemed unaware of the fact that she had become a woman.”

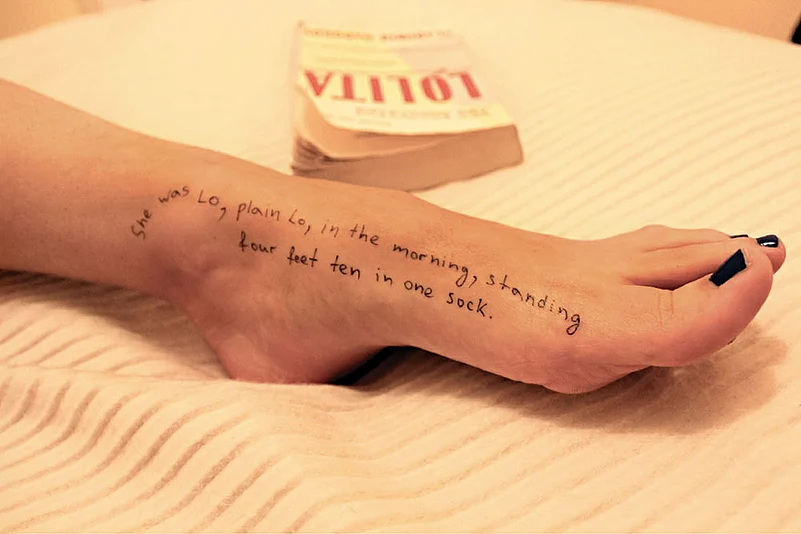

One puts away the violence of the blazing gun (which he carries) against the vulnerability of the two ducks (which she carries); likewise with aristocratic arrogance intruding into the lives of local villagers. But what does one do with this gaze, soon to become a fascination, with this rather un-Nabokovian Lolita?

Kantichandra, the gazing man, is a whole lot younger than Nabokov’s Humbert Humbert. And we still have family memories of marriages between older men and young girls. My own grandmother was 17 years younger than my grandfather, and I suppose such memories are fairly common. All of us who nourished our readerly sensibilities on 19th and early 20th-century Bangla literature know the disorienting homeliness of the child bride. It was Tagore’s own lived experience.

How does one recreate this disorienting familiarity for the 21st-century reader in English across the world? At a time when ethical anachronisms have led to much cancellation of culture? How does one translate this moment of disturbing beauty without making it sound creepy?

Is the age of sexual consent universal across time and place? Is it biological—the arrival of basic reproductive ability, or is it the age when reproduction is physically, socially and educationally advisable? Many communities across India have memories, in some cases, lived realities where child-brides are sent to homes of much older husbands as soon as they attain puberty—a custom that continues to horrify the modern liberal sensibility. But as thinkers such as Martha Nussbaum and Amartya Sen have argued, in order for lives, communities and nations to survive and thrive, we need to agree on principles of good, sustainable life that has to cut across cultural differences and come up with some degree of universal value.

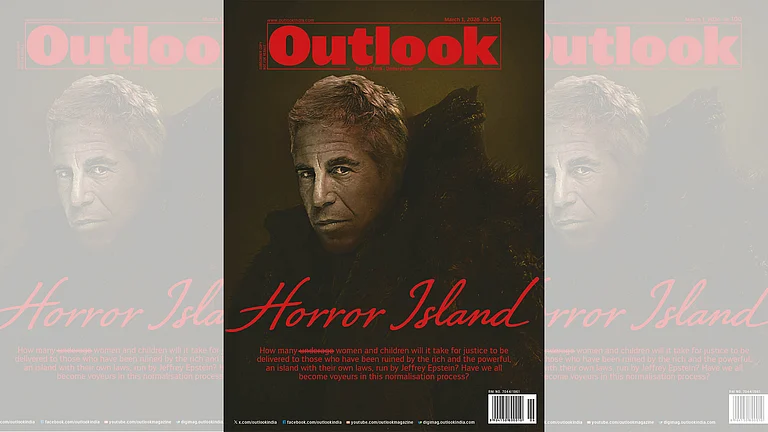

The repeated, inhumane, and systematically careless violation of the basic tenet of universal value, carried out over decades, far and wide, is what the Epstein files have made public. Sex with minor girls is horrifying enough, but not for the Epstein network—the victims must be passed around, trafficked across some of the most formidable networks of power, money, prestige and influence that straddle the Western world with its perverted collateral beneficiaries flung all across the globe.

What are the deepest meanings of this perversion? As with much of human behaviour, literature offers some shocking answers, even as the frame of art turns the sordid, the vulgar, and the perverse, into the subject of aesthetic inquiry. Like justice, art is blind, but in a radically different way. Art’s blindness is to moral value—or else, as Keats had asked, why would criminals make for far more interesting characters than saints? No wonder that in the murky realm of Shakespearean drama, the Iagos of the world will always out-dazzle the Imogens.

But even by that measure, I cannot think of a more radical definition of romantic love than the one taken by the American writer Lionel Trilling in ‘The Last Lover’, his 1958 essay on Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. Here, Trilling argues that the defining criterion of real romantic love is scandal. Most crucially, love can only exist in opposition to marriage, which is a pragmatic arrangement about property, offspring, and communal and political alliance.

“For scandal,” writes Trilling, “was of the essence of passion-love, which not only inverted the marital relationship of men and women but subverted marriage itself.”

What then, was a modern writer to do if they wanted to write about such love? Adultery, which once threatened the sanctity of marriage to the point of appropriate scandal, does poorly in modern times: “the very word is archaic; we recognise the possibility of its use only in law or in the past.” While the recognition of the fear of marital infidelity did it for the audience of Othello, it doesn’t cut much ice with modern audiences, for whom sexual jealousy is real but a moral assertion of that jealousy no longer sustainable. “The word ‘unfaithful,’” writes Trilling, “which once had so terrible a charge of meaning, begins to sound quaint, seeming to be inappropriate to our moral code.”

This paves the path for Trilling’s terrifying claim: that to maintain the true condition of passion-love, the writer must only tell the story that remains as far from marriage as possible, and widely out of the way of all practical consideration. Any working condition of “mutuality” would ruin everything, any concern for each other’s wellbeing or prestige would make it look like a marriage, and hence out of bounds of true passion-love.

“So that,” Trilling reaches his conclusion, “a man in the grip of an obsessional lust and a girl of twelve make the ideal couple for a story about love written in our time.”

These is a dangerous claim any time—which is exactly what Trilling declares his intent to be. But it is fated to come across as especially unsettling in an age where the hashtag #MeToo has deepened our awareness of patriarchal modes of sexual exploitation, and the manner in which they exclude women from the sphere of political and sexual agency. What do we make of this claim in a post-Epstein world, in a reality that we now know has been pervasively shaped by deeply-structured violation of women and children?

Biographical facts may introduce disturbing tremors here: Trilling’s own gender, race, age, position of power and privilege—those of Nabokov perhaps, and why not that of Humbert Humbert? The disrupted equation of moral codes looks a whole lot different surely when one is on the wrong side of the power game? Is it a whole lot easier to take aesthetic delight in the absence of “mutuality” as the marker of passion-love when the applecart of power tilts in your direction?

At a moment like this, the difference between art and life becomes as loud and clear as they can ever be. Trilling’s real concern is that of artistic representation; the novel of romance, more precisely. The moral freedom, indeed, anarchy that nourishes the soul of transgressive art is risky business in life; it can set us back by centuries of hard-earned freedom and progress.

In 2026, our world is long past child-marriage, long past older literatures’ valourisation of older men falling for pubescent girls. It is also long past the dazzling moral ambivalence of Lolita and Lionel Trilling’s radical celebration of its ethos. But it has now also come past #MeToo, and past the horrors of Harvey Weinstein and Jeffrey Epstein. Where do we look for universal moral values? Will the dangerous dalliance of art and intellect offer epiphanies, or will they only muddy our ethical clarities in a world gone mad?

This article appeared in Outlook's March 01 issue titled Horror Island which focuses on how the rich and powerful are a law unto themselves and whether we the public are desensitised to the suffering of women. It asks the question whether we are really seeking justice or feeding a system that turns suffering into spectacle?