Summary of this article

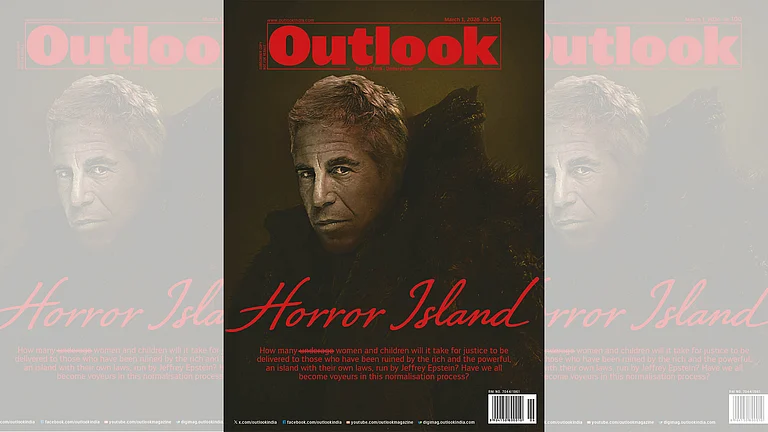

The release of documents linked to Jeffrey Epstein has led to resignations and mounting pressure on political and social elites across Europe.

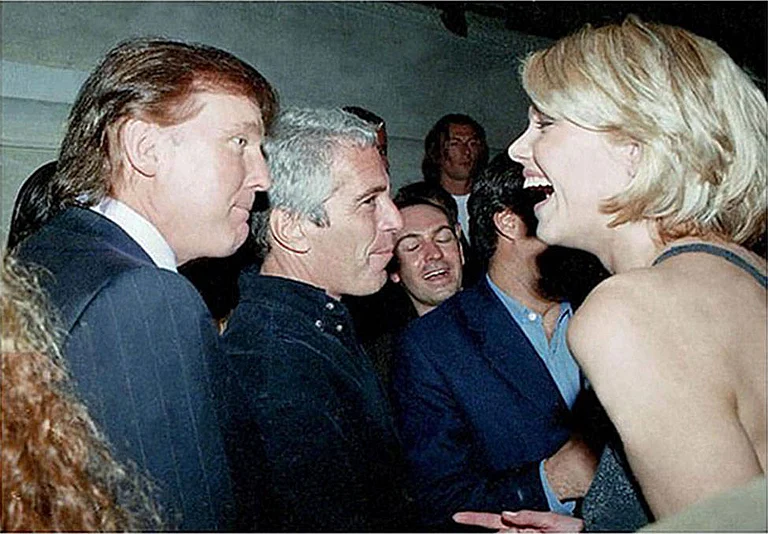

In contrast, prominent US figures with apparent ties to Epstein, including President Donald Trump and Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick, have largely retained their positions.

Journalists including Danielle Moodie and Carole Cadwalladr argue that media normalisation and limited sustained coverage in the US have contributed to the muted domestic fallout compared with Europe.

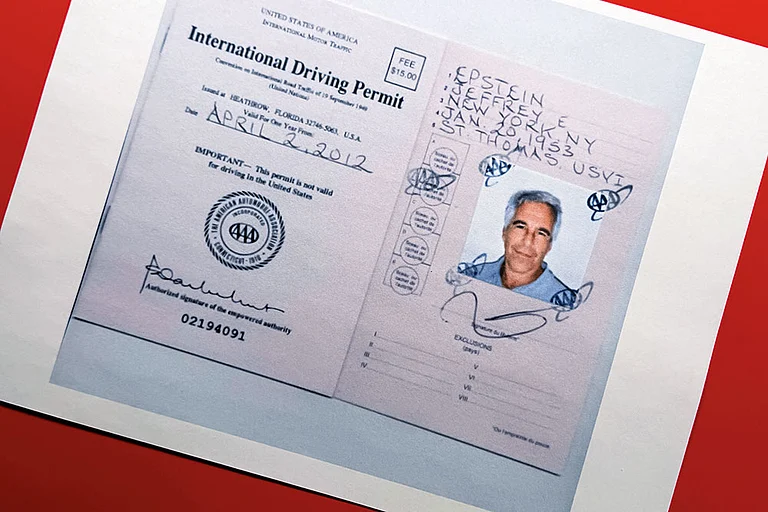

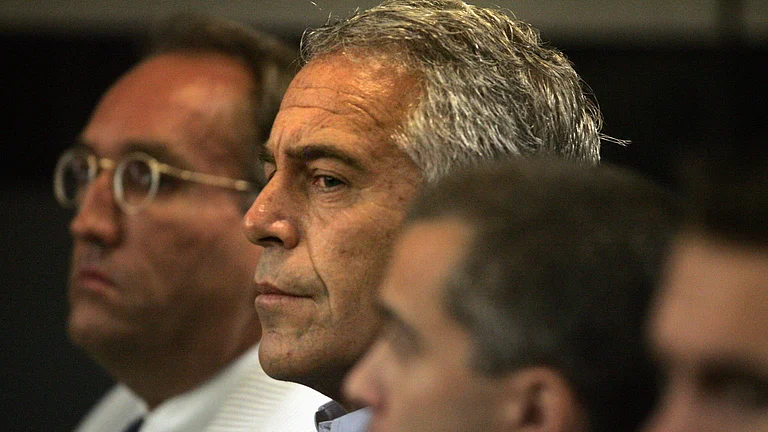

A prince stripped of his public role. An ambassador forced to resign. Senior diplomats and political aides pushed out of office. Across Europe, the release of documents linked to Jeffrey Epstein has triggered visible consequences for members of the political and social elite. There appears to be an Epstein domino effect. In the United Kingdom, Prime Minister Keir Starmer has lost an ambassador and two top aides over their connections to Epstein. Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor, already disgraced by his association with Epstein, remains under renewed scrutiny. Political and institutional figures in Sweden, Norway, France and Slovakia have also come under pressure.

Yet in the United States—the country where Epstein built his network, accumulated his power, and committed his crimes—the fallout ranges from limited to non-existent. Prominent Americans with apparent ties to Epstein—including President Donald Trump and Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick—have so far largely retained their positions of power.

Americans are waiting to see if anyone—anyone at all—will be held accountable. The contrast is striking. The chaotic way in which the files were released—including apparent failures in redacting the names of the victims and survivors—has exposed individuals whom the US Department of Justice was seemingly attempting to shield. Everyone knows who was there, and yet no one is being held accountable.

Danielle Moodie, host of The Danielle Moodie Show, framed the issue in broader historical terms to demonstrate the gravity of the issue. “I do not believe that if Richard Nixon was in trouble in this day and age that he would have had to resign. He would have had an entire media apparatus dedicated to gaslight millions of people each and every day that he did nothing wrong.”

The story itself has not gone entirely unreported. Corporate media outlets have mentioned the document releases, but often in passing. Cable news segments have acknowledged the developments briefly before moving on. Morning shows have covered the revelations perfunctorily, quickly shifting to lifestyle programming and entertainment previews.

For some journalists, this absence of sustained focus represents something more troubling.

“The most worrying thing going on in the United States is the scale of normalisation and the press is absolutely a structural part of that. And that is profoundly disturbing,” says Carole Cadwalladr, the award-winning investigative journalist whose reporting exposed the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal.

Cadwalladr’s most recent essay is headlined ‘We All Live in Jeffrey Epstein’s World.’ She sees the current moment as one that demands confrontation, not avoidance.

“Epstein should be the reckoning. Instead, we see this veil of silence. And I think the US press is not serving its readers and its viewers,” she adds. The issue, she argues, is not the absence of capable journalists.

She says that there is nothing on the front pages of The New York Times and The Washington Post today that spells out Epstein’s story and its importance. Media should have an element of moral leadership in these times.

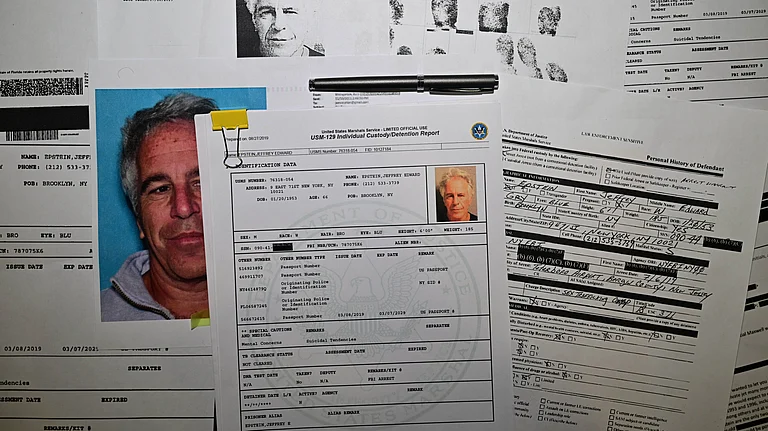

Since the Justice Department released millions of Epstein-related documents in January 2026, both The New York Times and The Washington Post have published over a dozen stories examining their contents and implications. But they put only one story on Page 1, which is surprising given historically front page dominance is associated with scandals implicating the political elite.

The reason for the recent reluctance by the mainstream press in naming the political and social elite who are in the Epstein files is the US defamation law—which while protective of press freedom—still exposes news organisations to extremely expensive litigation. Even if a newspaper ultimately wins a defamation case, the process can involve millions of dollars in legal costs, years of litigation and major financial strain. This creates a high internal bar before naming individuals in investigative exposés.

She also points to structural pressures within the media industry itself. “In the middle of this story, we saw this absolutely devastating and disgusting sacking of 300 journalists at The Washington Post. It’s another devastating blow to the press in the US. And for that to happen, in the middle of this particular news cycle, is a symbol of what is going on.”

The question, then, is not whether American journalists are capable of reporting such stories. It is why the institutional response has been so constrained.

According to Andrew Springer, a former ABC News journalist, part of the answer lies in the legal and financial power wielded by those at the centre of American political life, and corporate ownership of the mainstream press. Springer wrote a detailed essay on Medium titled ‘Why the Media Won’t Cover the Epstein Files.’

“Trump is a notorious litigator,” he writes. “If you have unlimited resources, you can take anyone or anything to court. You can bury the opposition in legal motions requiring thousands of dollars in attorney fees to even respond to. You can drag cases out for years; you can appeal and appeal.”

The objective, Springer suggests, is not necessarily victory in court, but deterrence. The cost of defending truthful reporting can itself become a form of punishment.

He points to a recent example when ABC News agreed to pay Trump an outrageous $15 million to settle a defamation lawsuit after George Stephanopoulos called Trump a rapist on air. This is despite the fact that a jury found Trump liable for sexual abuse, and the judge in that case explicitly said Trump’s conduct met the definition of rape.

Even demonstrably accurate reporting can trigger legal retaliation. And the threat of prolonged litigation, combined with shrinking newsrooms and economic precarity, shape editorial decisions. Newsrooms have been gutted, staff has been slashed and journalists are racing to hit the next deadline. They are busy churning out content to feed the algorithm, competing with a thousand other outlets for clicks.

Self-censorship over the Epstein files has become a major issue in the mainstream American press. Cadwalladr says, “I have been shocked—deeply, deeply shocked—by the absence of headlines, by the absence of sense-making across the US media that contextualises what is in these documents, that helps people to process them and to understand them. There is a sort of self-surrendering, self-censorship. And that, I find really deeply worrying.”

Springer writes, “You soften the language. You add more caveats. You move on to safer stories. You self-censor.” This, Springer argues, is not a failure of individual courage but a structural outcome.

Media organisations do not always require explicit instructions to limit their reporting. The structure itself encourages caution. When careers, lawsuits and institutional survival are at stake, silence does not need to be imposed.

“My former colleagues, many of whom are brilliant journalists who care deeply about the truth—also have mortgages. They have kids in school. They have medical bills and student loans and aging parents. And because we have virtually no social safety net in this country, they cannot afford to take risks that might cost them their jobs.” The result is a media ecosystem shaped as much by economic constraints as by editorial judgment. The system rewards engagement, stability and financial performance. It discourages risk.

The Epstein files were expected to illuminate a system of power that operated in plain sight, yet beyond consequence. Instead, they have revealed the uneven geography of accountability itself. In the US, the response has been filtered through a media ecosystem constrained by legal risk, economic fragility and proximity to power. What emerges is not simply a story about Epstein or the individuals in his orbit, but about the structural limits of scrutiny in a system where influence outlasts scandal.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Mohammad Ali is an award-winning journalist, based in Delhi. He is senior associate editor with Outlook