Summary of this article

The book features contributions from scholars, including Ashish Rajadhyaksha, Ranjani Mazumdar and Amrit Gangar, who analyse how cinema both reflected and contested authoritarian rule.

Taken together, the essays present cinema as a diagnostic instrument for Indian democracy.

Cinema and the Indian National Emergency offers a comprehensive and conceptually ambitious analysis to date of the Emergency’s cinematic legacy.

Summary of this article

The book explores how cinema during the 1975–77 Emergency was shaped by censorship, state control, and propaganda, while still enabling subtle forms of critique.

Essays examine film societies, state documentaries, parallel cinema, and popular Hindi films to reveal how cultural production negotiated authoritarian pressure.

The volume argues that the Emergency’s media logic persists today, influencing contemporary debates on visibility, dissent, and the politics of representation in India.

The Emergency of 1975-77 has long functioned as India’s political unconscious: a trauma periodically summoned in political polemic, journalistic nostalgia, and constitutional anxiety, yet it is only intermittently confronted in its full cultural density. With Cinema and the Indian National Emergency: Histories and Afterlives, edited by Parichay Patra and Dibyakusum Ray, this turbulent period receives the kind of media-archaeological and philosophically searching treatment that its visual life demands.

The book features contributions from scholars, including Ashish Rajadhyaksha, Ranjani Mazumdar and Amrit Gangar, who analyse how cinema both reflected and contested authoritarian rule. It presents the Emergency as not only a political crisis but also a pivotal moment in the Indian state’s self-representation on screen.

Fear of the Image

Rajadhyaksha’s opening chapter traces how the state regarded cinema as a volatile medium, capable of generating collective emotions it could neither predict nor manage. This anxiety prompted harsher censorship, expanded regulatory oversight, and a more aggressive deployment of the Films Division as an instrument of state communication. Rajadhyaksha’s argument resonates with political historians such as Christophe Jaffrelot and Pratinav Anil, who observe that the Emergency deepened the government’s suspicion of mass sentiment. In the cinematic sphere, this translated into an effort to recast the movie theatre from a forum of public engagement into a conduit for official narratives.

Patronage, Constraint and Film Societies

Amrit Gangar’s essay on the film society movement exposes the paradox of a regime that tightened cultural control even as it sought intellectual validation. Film societies were not dismantled; they were supervised. Letters, permissions, and programming decisions reveal a state intent on shaping the terms of cinephile discussion, even as figures like Mrinal Sen and Vijaya Mulay maintained spaces for critical reflection. Gangar shows that the Emergency’s media policy aimed not only to curb dissent but also to curate taste.

Sudha Tiwari’s chapter on the FFC/NFDC and New Cinema extends this tension. Throughout the Emergency, the state financed a wave of formally ambitious parallel films, producing an uneasy blend of creative possibility and ideological constraint. New Cinema became a mode of developmental realism that served technocratic agendas, yet directors used this opening to introduce doubt, irony, and critique. Tiwari frames this moment not as straightforward resistance but as a negotiation conducted within the state’s own cultural architecture.

This architecture of control becomes even clearer in the chapters by Ritika Kaushik and Vikrant Dadawala on state-sponsored documentary. Dadawala’s reading of S. Sukhdev’s After the Silence, which endorses the government’s Twenty-Point Programme, captures the Emergency’s attempt to rehabilitate itself visually. The films present a state at work—surveying the countryside, disciplining corruption, and modernising agriculture. Dadawala demonstrates how this imagery aimed to consolidate the moral authority of an embattled regime.

Kaushik examines the memos behind these documentaries to show how bureaucracy shaped filmmaking during the Emergency. Her analysis of official documents reveals that creative choices often followed administrative directives. In this context, documentaries became tools for government information management. Vinayak Das Gupta and Ananya Juneja note that these films now reappear in new documentaries and online, serving as reminders of state overreach rather than progress.

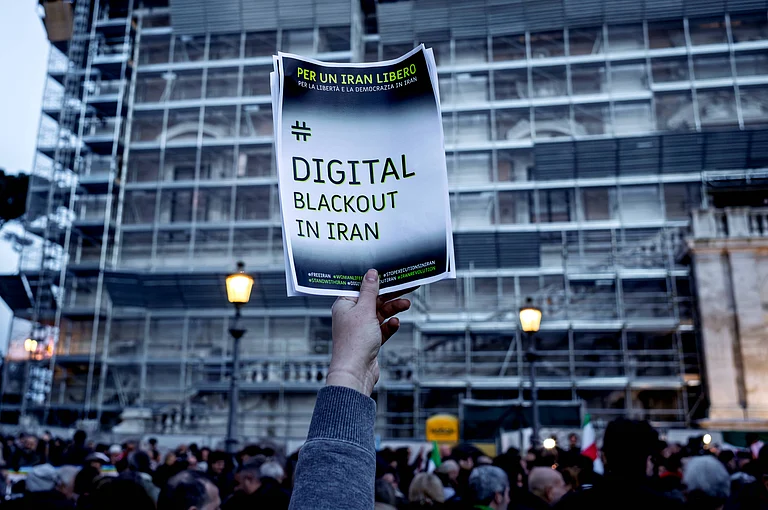

Ranjani Mazumdar provides a detailed analysis of the Emergency’s ongoing presence in the media. She focuses on cable news, where the Emergency is reduced to familiar images such as Sanjay Gandhi’s face, Indira Gandhi’s speeches, and dramatic headlines. Television retrospectives now frame the Emergency as a simple morality tale. Mazumdar contends that this repetition oversimplifies the era, turning genuine trauma into a routine narrative. Her perspective aligns with Gyan Prakash, who observes that Indian popular history often favours consensus over critical inquiry.

Authoritarian Echoes in Popular Cinema

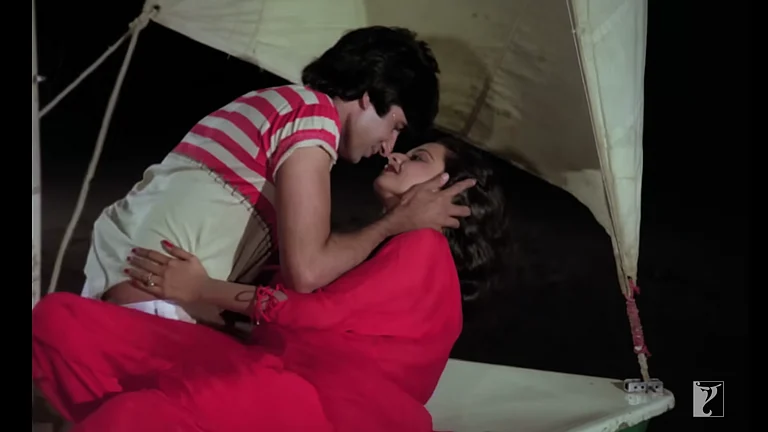

Dibyakusum Ray’s chapter examines how 1980s Hindi cinema absorbed the sensibilities forged during the Emergency. Tropes such as the angry young man, the corrupt officialdom, and the turn toward vigilante justice reveal how perceptions of authority were reshaped in its aftermath. The popular hero increasingly operated outside institutional frameworks, restoring order through extra-legal means. Ray shows that the Emergency’s imprint extended well beyond 1977, subtly reorganising popular culture’s moral and political imagination.

Alongside this, Parichay Patra introduces the idea of a “not-so-political cinema”: films not overtly engaged with state repression yet nonetheless shaped by its atmosphere. Under authoritarian pressure, he suggests, even apolitical narratives acquire a certain opacity, marked by muted emotional registers, abrupt ellipses, and tonal restraint. These formal shifts become part of the Emergency’s media history, revealing how cinema registers political tension without explicit declaration. Patra’s formulation unsettles the usual binaries of resistance and propaganda, offering a more nuanced account of how everyday filmmaking absorbs and refracts systemic pressures.

The Long 1970s

Kaushik Bhaumik concludes the volume by situating the Emergency within the broader context of the “long 1970s.” He interprets Anjan Dutt’s work as a record of this extended crisis, capturing the decade’s disillusionment, fragmented political energy, urban anxieties, and institutional distrust. Bhaumik expands the temporal and emotional scope, demonstrating that the Emergency’s cultural impact extends beyond its official duration.

Diagnosing Indian Democracy

Taken together, the essays present cinema as a diagnostic instrument for Indian democracy. The Emergency was more than a constitutional rupture; it was a crisis of visibility and perception, raising fundamental questions about image control, spectatorship, and the politics of representation.

The book argues that the Emergency’s media regime persists, its assumptions about managing dissent and disciplining images still shaping contemporary media culture. It acknowledges the unevenness of cinematic resistance, the ambivalence of institutions, and the compromises that marked creative practice. At the same time, it illuminates the resourcefulness that persisted within Emergency-era filmmaking—its coded critiques, aesthetic detours, and negotiated spaces of autonomy. The volume shows how filmmakers worked within, around, and sometimes against state structures without surrendering cinema’s expressive possibilities.

Cinema and the Indian National Emergency offers a comprehensive and conceptually ambitious analysis to date of the Emergency’s cinematic legacy. It skilfully integrates political theory, media archaeology, and historical analysis to show how images can both support and challenge authoritarianism. As debates about censorship, surveillance, and media manipulation resurface, this volume serves as a timely warning. Although the Emergency ended in 1977, the book demonstrates that its media-political framework continues to shape India’s self-image on screen.

The author is a poet and critic in Urdu and English. He teaches South Asian Literature and Culture at the University of Vienna, Austria.