Summary of this article

The Indian People's Theatre Association was born in 1943.

It came up amidst the roused spirits of the anti-colonial movement in India and the global turmoil of World War II.

Their agenda was that in historic times of political unrest, art must reflect the reality of the suffering masses and be transformed into a weapon to mobilise them.

What do the social disillusionment of Guru Dutt, the ache of Partition and collective loss in Ritwik Ghatak and the foundational political consciousness of Salil Chowdhury have in common? Their umbilical cord to a movement that radically transformed the history of Indian cinema.

The stark disparities between the haves and the have-nots would not sear the screen as poignant poetry, if not for Abrar Alvi’s writing and Sahir Ludhianvi’s lyrics in Pyaasa (1957). Nita’s (Supriya Chowdhury) angst would not have echoed the uprooting and homelessness of thousands during Bengal’s Partition, if not for Ghatak’s cinematic exposition of trauma and the moving score composed by Jyotirindra Moitra for Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960). “Aye Mere Pyaare Watan” from Hemen Gupta’s Kabuliwala (1961), pictured on the longing of an Afghan dry fruit seller for his land and people, would not go on to evoke patriotic fervour for times to come, if not for the yearning notes from Chowdhury.

As the birth centenaries of these three stalwarts coincide with hundred years of the Left movement in 2025, this is an opportune moment to look back at the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), which gave Indian cinema artists, whose work cemented what is now popularly called the “golden age” of the film industry.

Born in 1943, amidst the roused spirits of the anti-colonial movement in India and the global turmoil of World War II, the roots of IPTA’s inception lay in the Progressive Writers’ Association, which emerged during the 1930s in an attempt to foreground literature that was socio-politically conscious and contributed to the ongoing political struggle against the British.

Born in 1943, amidst the roused spirits of the anti-colonial movement in India and the global turmoil of World War II, the roots of IPTA’s inception lay in the Progressive Writers’ Association.

Presided over by Prof Hiren Mukherjee, IPTA’s first conference was held on May 25, 1943 at Bombay and several luminaries from the world of cinema as well as performing arts were present during this pivotal occasion, ranging from film director Bimal Roy to dancer and choreographer Uday Shankar. The agenda was clear—in historic times of political unrest, art must reflect the reality of the suffering masses and be transformed into a weapon to mobilise them towards the anti-colonial cause and the redressal of existent social ills. The manifesto they adopted enshrined a resolution to this end, stating, “We, writers and artists, singers and dancers, painters and musicians, technicians and cultural workers of the stage and screen, assembled under the banner of the Indian People’s Theatre Association, dedicate ourselves anew to the cause of the people.”

While many historians credit IPTA’s foundation to the Communist Party of India, the movement also drew artists who were not explicitly associated with the Left party. Nevertheless, they all espoused similarly progressive values and were equally committed to the goals of the anti-imperialist and anti-feudal struggle.

A classic example of this was Dutt, who was never directly associated with the movement but had an intimate work relationship with Alvi and Ludhianvi. That was how songs like “Jinhein Naaz Hai Hind Par Wo Kahan Hain” and “Ye Duniya Agar Mil Bhi Jaaye Toh Kya Hai” came to be haunting indictments of the existent society in Pyaasa, at a time when the facade of national integration pushed social troubles into the shadows. Issues of class inequality, peasant struggle, caste discrimination, communal harmony and women empowerment organically found their way into theatre and cinema during this period, even as they flirted with the boundaries of censorship.

Together, IPTA artists came up with productions that would employ themes and frameworks of exhibition hitherto unheard of. The intent behind this was to redeem art and theatre from elite gatekeeping and make it accessible to the people that it was meant to represent. Bijon Bhattacharya’s Nabanna (New Harvest), directed by him and Sombhu Mitra in 1944, was the first major production that was taken by IPTA across the country. Known for its social realist performing style, it became a groundbreaking work of influence, which brought many more artists, including Ghatak, under the fold of the movement. The play depicted the 1943 famine in Bengal through the ordeals of Pradhan Samaddar, a Bengali peasant and his family. It was performed as an effort to raise funds for the people at the receiving end of the crisis. As Prof Neera Chandhoke has pointed out in The Wire, Nabanna was radical in its politics because it critiqued not just British policies while highlighting that the Bengal famine was man-made and not natural, but also the Zamindari system, for keeping the farmers severely impoverished.

Nabanna and Moitra’s Naba Jiboner Gaan (Song of New Life) went on to have a significant impression on the films that were made by filmmakers associated with IPTA. Chetan Anand’s Neecha Nagar (1946), Khwaja Ahmad Abbas’s Dharti Ke Lal (1946) and Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zamin (1953)—all drew their aesthetic inspiration from these plays. Each of these films attracted international recognition on various global platforms for its realist form, grounded performances and moving subjects.

Dharti Ke Lal shares its main theme of the plight of farmers during the Bengal famine with Nabanna, which was a major influence on Abbas’s script, co-written with Bhattacharya. Alongside were the impressions of Jabanbandi, another play by Bhattacharya and Annadata, a short story by Krishan Chander. Interestingly, the film was also crucial in helping expand the market for Indian films in the Soviet Union—a factor that later also benefited Raj Kapoor’s films like Awara (1951).

Anand’s Neecha Nagar, which was written by Abbas and Hayatullah Ansari and drew from Maxim Gorky’s The Lower Depths (1902), is the only film that has ever won a Palme d’Or at the Cannes film festival, even as it ironically did not release in India. The film highlighted the corruption of the rich and their exploitation of the poor for their resources and perhaps drew the ire of colonial censors because of its spectacular depiction of the mobilisation of masses for their basic rights.

Do Bigha Zamin, much like the earlier two films, foregrounded the alienation that a poor farmer experiences when he moves to the city to earn in a bid to save his land. The story, based on Rabindranath Tagore’s poem Dui Bigha Jomi and Salil Chowdhury’s short story Rickshawalla, had Balraj Sahni as the protagonist, also a member of IPTA. Reportedly, Roy made the film after watching Vittorio De Sica’s famous neo-realist work Bicycle Thieves (1948)—something that reflects in the film’s conceptualisation, formal texture and overarching thematic.

While many historians credit IPTA’s foundation to the Communist Party of India, the movement also drew artists who were not explicitly associated with the Left party.

Apart from these personalities, IPTA gave the Indian film industry many other eminent figures such as Utpal Dutt, Kaifi Azmi, Shaukat Azmi, Hemanga Biswas, Pt Ravi Shankar, Prithviraj Kapoor, AK Hangal, Durga Khote, Satyen Kappu, Dina Pathak, Basu Bhattacharya, Shailendra, Majrooh Sultanpuri and MS Sathyu—who ranged from directors to writers and lyricists as well as actors and musicians. This influx into the industry had a rhizomatic impact on the productions of the time. Each of these figures became instrumental in carrying forward the Left-leaning progressive politics of the platform through their work.

The interesting aspect of this period was that most IPTA-associated directors would bring in cast and crew who were also part of the organisation, giving way to the consolidation of a framework where nuanced critiques of social realities came to dominate Indian cinema’s consciousness in general, and Hindi cinema’s in particular. The fact that their collective efforts put Hindi cinema on the global map, while also finding commercial footing, led to this period being recorded as the industry’s most prolific and memorable juncture.

However, their influence didn’t end just there. Some among these members, most famously Ghatak, also went on to teach in prominent institutions like the Film and Television Institute of India. Though his tenure at the institute was brief, Ghatak managed to leave an indelible imprint on another generation of filmmakers like Mani Kaul, John Abraham, Adoor Gopalakrishnan, Kumar Shahani and Saeed Akhtar Mirza. These directors further gave Indian cinema a parallel wave in the late 1960s and 1970s across different linguistic industries, where an authentic filmic style and a refreshing artistic perspective that broke away from the conventions of mainstream industrial produce came into being.

It is true that the rapidly changing political landscape within and beyond the country and the response of Left organisations to these circumstances led to numerous ideological splits that also impacted the structure of IPTA. Eventually, the platform broke into multiple groups, among which the Bombay faction of the organisation thrives even today. Nevertheless, IPTA’s legacy still cascades through the cultural and cinematic heritage of the country as the vision IPTA offered to Indian cinema continues to remain timeless—a commitment to art that is created not just for art’s sake, but to invigorate the collective spirit of the viewer, the citizen, to move towards social betterment. Today, while certain directors go out of their way to portray Left ideology as the real villain of the Indian society through their films, audiences will do well to remember what the politics, and the artists who espoused its values, have given to the film industry for posterity.

Apeksha Priyadarshini is senior Assistant editor, Outlook. She writes on cinema, art, politics, gender & social justice

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

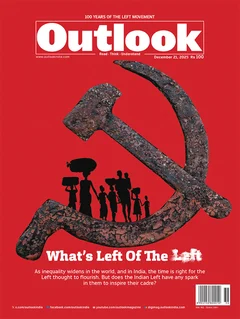

This article appeared as Aye Mere Pyaare Watan in Outlook’s December 21, 2025, issue as 'What's Left of the Left' which explores how the Left finds itself at an interesting and challenging crossroad now the Left needs to adapt. And perhaps it will do so.