While politically, Bihar has always been dynamic, Bollywood has singularly imagined the region through the framework of crime, politics and violence.

Filmmakers like Prakash Jha have remained focused on the power gambles in the region for their films.

This imagination, however, is changing with indie filmmakers like Achal Mishra and Parth Saurabh.

The dust from the endless political rallies in the hinterlands of Bihar is finally settling down as the state’s nearly 4-crore citizens go to vote in two phases for the Assembly elections. Bihar’s intriguing political economy can be understood from the wide spectrum of political parties that are standing for elections in the state. A multitude of ideologies have found a footing and flourish in its soil, characterising a region where the stakes in power are always dynamic, even as it has, in many ways, stood still in time.

This dynamism, however, has eluded the imagination of Bihar in mainstream Hindi cinema. In the last few decades, the region, historically known for its cultural richness, has been wrought singularly in the visual framework of crime, politics and violence. A range of films from N. Chandra’s Pratighaat (1987), Prakash Jha’s Damul (1984), Mrityudand (1997), Gangaajal (2003), Apaharan (2005) and Jai Gangaajal (2016), Anurag Kashyap’s Gangs of Wasseypur I & II (2012), to the more recent Sony Liv series by Subhash Kapoor Maharani (2021-ongoing) and Netflix film Bhakshak (2024) by Pulkit are driven by such overarching themes. Corrupt politicians, their criminal nexus with baahubalis (regional strongmen), feudal violence perpetuated on the basis of caste and gender, gang wars and merciless killings become recurrent plot points that drive the narratives within these films.

This is not to say that the representation of the region’s socio-political maladies in these films is skewed. Many of these works have been inspired by true events, which shook the country and made citizens sit up and take notice of the repetitive, blatant breakdown of law and order in the state. Gangaajal was premised on the infamous Bhagalpur blindings that took place between 1979 and 1980 in Bhagalpur, Bihar. The incident involved the police indulging in the terrorising act of blinding undertrial prisoners by pouring acid in their eyes. The case drew attention to the extrajudicial violence that prisoners are subjected to in jails; the film, in turn, threw light on the complex social reality of the region where citizens, who were exhausted with criminality permeating their everyday existence, initially lauded the police for the heinous act. Bhakshak highlights the Muzaffarpur shelter home case in 2018, where more than 30 instances of sexual assault, abuse and torture of young girls were reported at a shelter home in Muzaffarpur, Bihar. While the case was uncovered after an audit of shelter homes across Bihar by a Tata Institute of Social Sciences (Mumbai) team in 2017, the film shows the role of the media and the pursuit of one small-time, but fearless journalist in unmasking the powerful political figures behind the incidents.

Some of these films also draw on the lores surrounding real-life figures to carve stories against the backdrop of the region. For instance, Pratighaat drew its main antagonist from Kali Prasad Pandey, a prominent baahubali in the 80s and 90s in Bihar, who also served as an MLA and MP from the state and was known for his “Robin Hood” image. In the series Maharani, the main protagonists are rumoured to have been sketched loosely on Lalu Prasad Yadav and Rabri Devi, and the narrative has included many incidents from their rule in the state. Then, of course, there are the characters in Gangs of Wasseypur—Ramadhir Singh, who was adapted from the criminal-politician Suryadeo Singh; Shafiq Khan, who inspired Sardar Khan; and the notorious Faizal Khan, who’s role took off from the real-life Faheem Khan.

However, what remains noteworthy is the consistent fascination of Bollywood’s filmmakers with the crime-power nexus in the region—to the extent that this interest overshadows every other creative perspective through which Bihar’s landscape can be observed. There are some films, nevertheless, that have used this narrative framework to draw attention to broader underlying social issues. Mrityudand, for example, looks at the patriarchal stronghold in a feudal society and imagines a scenario where women fight back. Damul reflects the deeply-entrenched caste-based hierarchies and the brutal repression that the poor and the disenfranchised have historically been subjected to in the state.

There are also a precious few films like Ketan Mehta’s Manjhi-The Mountain Man (2015)—a biopic on the real-life figure of Dashrath Manjhi, who carved out a road from a rocky mountain over a period of 22 years after losing his beloved wife to injuries from falling off the mountain ridge. The film spoke not just of an individual Dalit labourer’s unflinching determination, but also emphasised the gross structural failure of the state in providing the most basic amenities to its citizens, many decades after its independence.

But where Bollywood has left its artistic pursuits, indie filmmakers have picked up the threads and begun to weave something new and refreshing. Filmmaker Achal Mishra, who debuted with Gamak Ghar in 2019, humbly took on the task of bringing Maithili—primarily spoken in the Mithila region (comprising of northern Bihar and parts of Nepal)—into the artistic fold of cinema. The film, an ode to his childhood memories, is a poetic tale of homes left behind by their inhabitants, who move ahead in search for more promising avenues and seldom return to stay. He followed it with Dhuin (2022), based on the dilemma that a young theatre artist faces of choosing between his dreams and his responsibilities. As the ambitions of making it big in Mumbai as an actor drive his aspirations, the financial crisis that his family undergoes keeps him tied to his hometown.

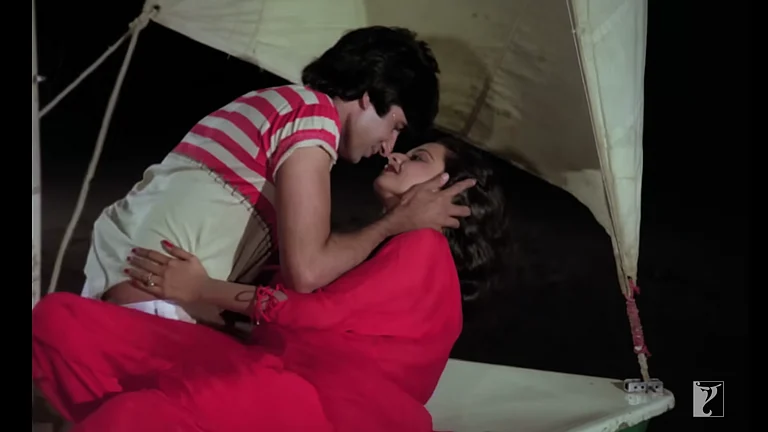

Not only does Mishra attempt to portray the lives and losses of those who exist at the margins of mainstream Indian cinema’s imagination, he is also boosting the endeavours of fellow filmmakers who have embarked on similar journeys. Pokhar Ke Dunu Paar (2022), directed by Parth Saurabh, follows a simple tale of two lovers in a small town, who choose to elope, but are held back by social and financial constraints and are on the verge of returning to their older lives. The film was also produced by Mishra and drew inspiration from his stylistic underpinnings in its attempt to visibilise the vagaries of lives that lie outside of metro cities.

Even as indie filmmakers evoke the hope that Bihar as a landscape can be portrayed on the big screen in colours other than that of blood, it remains to be seen whether Bollywood will look past its preoccupation with the power gambles of region and explore the vibrancy that the state has to offer.