Summary of this article

Nidhi Saxena's second feature Secret of a Mountain Serpent premiered at the Venice Film Festival.

It screened at the 30th IFFK.

In this interview, Saxena spoke about how she began to differently view the film's moral dilemmas

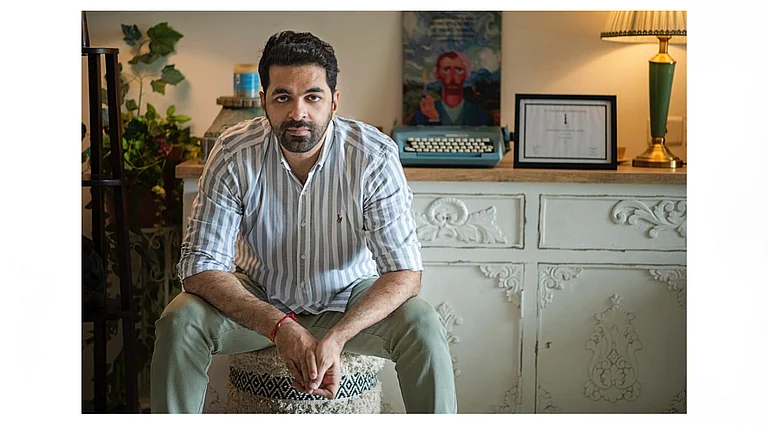

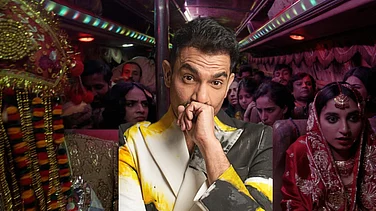

In her sophomore feature Secret Of A Mountain Serpent, Nidhi Saxena conjures a fable of yearning. With the Kargil War in the background and her husband in the army, Barkha (a subtle, radiant Trimala Adhikari) is struck in disconsolate loneliness. A sudden stranger (Adil Hussain, elusive as ever) brings charms too powerful and seductive to resist. Saxena works in attrition, carving out soft signals and messages for characters to transmit. Wordier passages are eschewed for something more tender and embalmed right on the heart.

Ahead of the film’s screening at the 30th International Film Festival of Kerala (IFFK), Nidhi Saxena sat down with Outlook’s Debanjan Dhar to discuss shifts in conditioning, the film’s remarkably swift shaping and cinema as a nourishing expression. Edited excerpts from the conversation:

You said that you conceived the story some ten years back while living in Almora. What did that basic kernel of the project look like?

When I was in Almora, I was meeting a lot of women whose fathers and husbands were in the army. Even my landlord’s son and husband used to come twice in the year. I felt empathetic towards the soldiers’ widows. I didn’t see them as individuals who had every right to go out and love and explore. Gradually, I got to know that they aren’t entirely unhappy with their husbands’ deaths. It was very shocking. They also liked someone in the town and had affairs. It took me some time and age to accept them. I was working in Almora in 2012 with a few NGOs. The seed came from there. With time, I started to feel the women’s absence of love.

You see the screenplay as a living thing, but do you write very detailed screenplays or outlines of the shots in exact terms?

Not at all. When I was at the screenplay lab, I told one of the mentors that I do want to explore more while making the film, that I might not have all the specific answers then and there. If the secrets open up entirely before making the film itself, what’s left? Even when I won the production grant, they mentioned I won not because of a screenplay, but the treatment. I usually write images. I submitted a long five-page note around desire—how I see it in everyday life.

While creating these images with DP Vikas Urs, do you share early sketches?

Vikas doesn’t like to see references that much. We did a very extensive pre-production. There were things which I changed, of course. Like that shot of Trimala standing by the tree, where you see the fire, I imagined it differently. Now the fire is more in-your-face and unreal. I exchanged a lot of Raja Ravi Varma and Amrita Sher-Gil paintings with Trimala. I asked her if she could stand and see in a particular way. And she did it!

Like your previous film, this one is also not so much hinged on story and traditional elements as it is on evocation and a certain imaginative allowance given to us. For devising this interplay between expression and withholding, is it a very natural, intuitive process or do you chip away with constant, deliberate omission?

I’m making films out of a desperate need for expression. I was a painter and sculptor. I come from a humble family and had to pause painting because money wasn’t coming in. There were no remaining sources of motivation. Films are nurturing me. They help me in self-reflection. There’s a need to see, recreate and retell our past. I did know of film as a possible expression from childhood. I have always been an avid reader and would recreate scenes. I used to act out characters from Crime and Punishment. I’ve painted those scenes also but it wasn’t sufficient.

Navigating pitching, grants and script labs can be daunting for a first-timer. Did you have a support system to rely on for advice?

Not at all. I read up and checked out which films have appeared at Cannes or Venice. But I’m well aware that my films aren’t giving what foreign audiences typically desire. Whatever we do, I feel we’ll always seem a third world country to them. When I was pitching the film, I wrapped it in Kargil. In the film, the war isn’t very evident.

Do you also feel the mentors can change the trajectory of the project if you don’t have a clear idea?

Totally. This film has changed a lot. Sometimes I feel it might have been more beautiful if I’d made it the original way. Earlier, there was a voiceover threading the entire film. But I do love being unsure and ambiguous.

Since the film speaks in this whispery cadence and it’s such an internal drama, I was curious how you shape performances. Are you very particular with your actors, design the precise beat of how they are to speak and move, or allow a more fluid exchange?

I don’t totally set them free . I fix the frame and imagine some of the moments. I make sure they follow them. It’s very tightly framed. Adil told me I’d written something in the script that he’s supposed to look dangerously at her. He commended it’s good writing. It’s better than the usual brief which is to look angrily or smilingly. ‘Dangerously’ gave him space to imagine possibilities. I did trouble Trimala a lot with particular instructions.

Do the workshops with actors cohere specifically to the script or wind into other probable scenarios?

I spoke to them about their personal lives. I talked to Trimala about morality, absence of love and men. I’d walk a lot with the actors. If you get the rhythm with the walk, you might get everything else.

I was also wondering about the quickness with which you made this film, finishing this barely within ten months. Does that pace bring fundamental changes in your way of working?

Yes, of course. I was selected for the lab in October and delivered the film in August. I just had the synopsis and treatment in October. I wrote the screenplay, cast the actors, assembled the team, did the recce and post, all within ten months. It changed me as a human as well. With Sad Letters Of An Imaginary Woman (2024), I took more than a year to edit. With this film, I’m still editing in my mind. It’s difficult to know when to stop. Sometimes, all it takes is compulsion. Today, I’m saying I’m satisfied with Sad Letters…That might not be the case at all few years later when I revisit it.

Can you talk a bit about Vimukthi Jayasundara’s mentorship? Take me back to how you met, what that journey of collaboration has been like…

When I was at FTII, he came in to do a workshop with the direction students. When I’d shot Sad Letters… and was looking for an editor, a friend connected me to Saman Alvitigala, Vimukthi’s editor. Saman suggested asking Vimukthi to come on board. In Sad Letters…, Vimukthi talked about the color and made me rethink the ending. Now, he has been telling me to make a commercial film else I’d be slotted an art filmmaker.

How was the reception at the India premiere in the Dharamshala Film Festival?

The response was overwhelming. I think our film got the longest queue. They had to do another screening in a bigger hall. The film is in the vein of the kind Mani Kaul made. I was really surprised by people sticking through my film at Dharamshala. I thought Indians are tuned to watch a film which is closer to classical music. Of course, such films can’t get popular.

Are you working on anything new?

I’m working on a very commercial screenplay (laughs). It’s narrative and very accessible. I’m pitching it around to some actors. It’s called Azad Nagar.