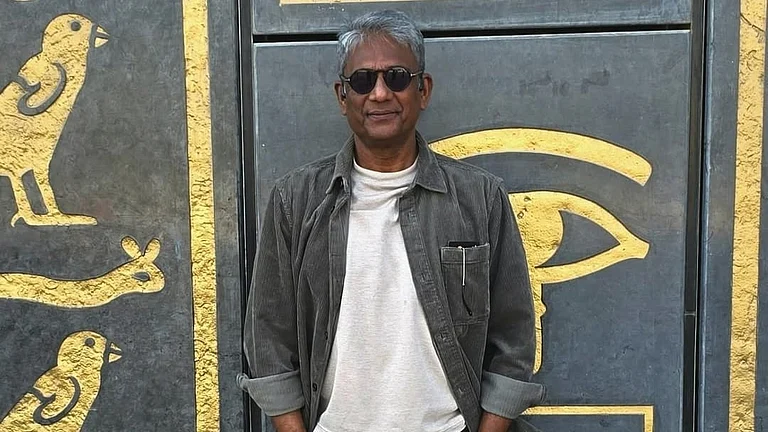

Actor Adil Hussain came to Dharamshala International Film Festival 2025 with Secret of a Mountain Serpent.

His well-known films include Life of Pi (2012), Mukti Bhawan (2016) and English Vinglish (2012).

Secret of a Mountain Serpent premiered at the Venice film festival and has been earning accolades in the festival circuit.

There’s a rare quietude that Adil Hussain brings both to his performances and his presence, a stillness that feels almost radical in an age of spectacle. The acclaimed actor, known for his work in Life of Pi (2012), Mukti Bhawan (2016) and English Vinglish (2012), returned this year to the Dharamshala International Film Festival (DIFF) with Secret of a Mountain Serpent, a meditative new feature directed by Nidhi Saxena. The film, which premiered at Venice and has been earning accolades in the festival circuit, delves into desire, solitude, and the subtle shades of human longing.

In a candid chat with Siddhant Vashistha for Outlook India, Adil Hussain reflected on a life in cinema, the advent of AI, his association with DIFF and the new film. Edited excerpts from the conversation:

You’ve been closely associated with independent cinema from the beginning. What makes DIFF special for you?

DIFF, in my opinion, is the best film festival in the country, period. There’s no red carpet, no gloss or glitter. Even the opening ceremony is simple: the director of DIFF says a few words, and the films begin. I’ve always believed that if there’s any “star” to be celebrated at a film festival, it should be the film itself, not the people who made it. We are servants of art.

That philosophy is what sets DIFF apart. When I first came here, I was so relieved to find no red carpet. I’ve always cringed at that culture. It’s unfair to the rest of the cast and crew. Why only celebrate the actor, when the cinematographer, the spot boy, the sound engineer, and the rest of the film crew have all given their blood and sweat?

I also admire DIFF for its integrity. Last year, three of my films were submitted but none were selected, even though I’m on the advisory board. That’s exactly why I respect this festival. It doesn’t operate on favouritism or networking—it believes in merit.

A festival like DIFF celebrates a microcosmic understanding of the human condition. It zooms in on the ordinariness of human life, but finds magic in it. Most of the films you see here are not grand-scale films. They study the human condition in the minutest possible way.

Your film Secret of a Mountain Serpent premiered here. Tell us about it.

It’s a study of longing and passion, primarily through the experience of women. But before being women, they are human, and that humanity is what the film explores. Nidhi (Saxena), the director, has done a brilliant job. The film premiered in Venice and recently won ‘Best Film by a Young Director’ at the Bangkok International Film Festival. It’s again a film that requires a rasik to watch.

What is a rasik here?

Rasik is a Hindi word for someone who has acquired a special taste. You have to be a rasik to appreciate something subtle like classical music, or Bhimsen Joshi, or Abdul Karim Khan. You need to educate yourself to appreciate something that’s not obvious.

Like a jeweller who can spot a diamond within a rock, the viewer too must develop that eye. Sadly, we live in times when stories are often simplified or “dumbed down” for mass consumption.

We live in complicated times, AI is making its way into art and film. As someone who has worked across the world, how do you see this affecting cinema?

I’ve been listening to a lot of specialists, even those who have invented AI. I’m very apprehensive because it feels like a wildfire—you don’t know which way the wind will blow or what it will burn in its path.

Recently, an AI actor called Tilly Norwood was launched by a Dutch woman (Eline Van der Velden). I was interviewed by the BBC about it. And I said, I’m surprised that such a “digital actor” was launched at a film festival (Zurich Film Festival)! At least film festivals should not do that. Why would we celebrate something non-human when cinema is about the human condition?

There’s been a big backlash in Hollywood. I’m a member of the Screen Actors Guild (SAG-AFTRA), and they’ve signed a contract protecting human actors. DC Comics also announced that they will never use AI, and I retweeted that news. I think they were very bold to do so, because if one corporation can take a stand, maybe others will too, though I doubt it. Most corporations are driven purely by profit. I don’t believe they care much for art or human well-being. That’s true not only of film studios, but also big pharma, big tech, food industries, tobacco, coal—all of them.

To care for human well-being, you need empathy. You need to understand what “human well-being” even means—and empathy for every human being, not just the one percent who hold most of the wealth. That’s my worry. But I still try to stay hopeful. Even though it’s a pessimistic situation, I keep my hope alive. I believe that human beings will always long for human actors, for something real.

You and I could have done this interview over Zoom or a phone call, but meeting in person, feeling the other person’s presence and vibration—that’s something else. That’s what makes us human.

Your home state Assam lost an icon in Zubeen Garg. What does his passing mean to the cultural community there?

He was very unique. After Bhupen Hazarika, Zubeen Garg was one of the few musicians who spoke directly to the unspoken thoughts of the youth. He wrote about unfulfilled romance, social indifference—things that people felt but couldn’t articulate. And he did it in such simple words that they went straight to the heart.

He was fearless. He said, “I don’t believe in religion or God. I’m a social leftist.” But what he really meant was that he believed in equality. And any human being with empathy would want an equal society—you don’t have to be a leftist to believe that.

I also wonder why one percent of people in India should have 40–60 percent of the wealth. It makes no sense. Since the time I’m aware of politics, governments have always helped one section of society, and he questioned that through his songs. That’s why he was loved, because he spoke through a popular medium—not as a politician but as a poet of the people.

It’s a big loss for Assam. There are very few artists who speak for the people and still remain trusted and loved.