Summary of this article

Sara Khaki and Mohammadreza Eyni’s Cutting Through Rocks follows Sara Shahverdi, the first-ever elected councilwoman in her remote, patriarchal Iranian village.

Shahverdi challenges entrenched gender norms by training teenage girls to ride motorcycles and campaigning against child marriage.

The film won the World Cinema Grand Jury Prize: Documentary at Sundance earlier this year and had its India Premiere at DIFF 2025.

Imagine a village in Iran, conservative and underdeveloped, run by archaic laws. Now imagine a divorcee, woman biker and councilwoman in that same village. Sara Khaki and Mohammadreza Eyni’s Cutting Through Rocks begins with this bold premise and offers a visual treat as unique as it can get.

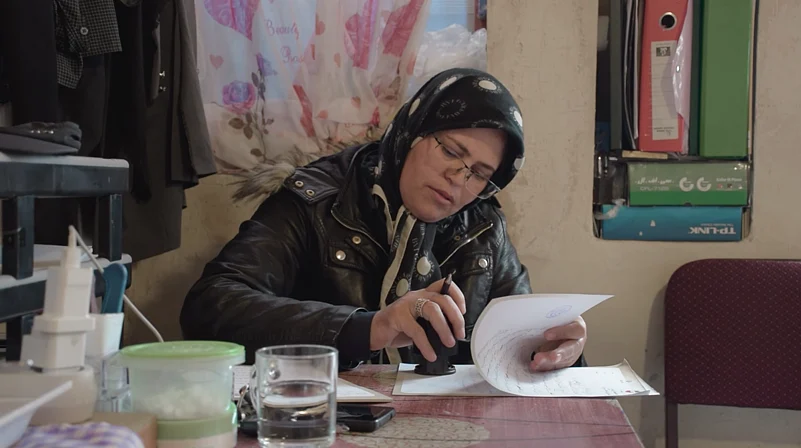

The film follows Sara Shahverdi, the first-ever elected councilwoman in her remote, patriarchal Iranian village. With fearless determination, she challenges entrenched gender norms by training teenage girls to ride motorcycles and campaigning against child marriage. But as her reform efforts gain momentum, skeptics question her motives, sparking personal and political backlash. The film captures Sara’s resilience, her political ambition, and the emotional toll of challenging tradition, offering an intimate portrait of courage and transformation.

The film won the World Cinema Grand Jury Prize: Documentary at Sundance earlier this year and had its India Premiere at the Dharamshala International Film Festival (DIFF) 2025, receiving a roaring response.

A Game of Contrasts

From the get-go, the documentary film relies heavily on stark contrasts. These contrasts are built showing a woman protagonist going against the fold in her village. The film uses these visual and situational opposites consistently to highlight the friction between entrenched conservatism and the transformative potential of one courageous individual.

Sara not only rides a motorcycle but dares to teach it to young girls as well; she doesn’t just exist as a woman asserting her rights in this setup but also dares to exercise power by running for a councilwoman and then winning the election. She uses her education not just to ensure the rights for women but also teaches other young girls who would otherwise be married in their early teens.

These layers of contrasts also start weighing heavily on the audience, making one question if it is all too much and may come crashing down. And crashing down it does come—the film doesn’t shy away from showing the backlash Shahverdi faces, through formal complaints accusing her of running a “dishonourable house,” public humiliation, and societal restrictions that aim to silence her. Sara herself acknowledges early in the film that doing something unconventional “sometimes comes with a cost,” and the narrative returns to this truth again and again, showing the emotional and social price of defying norms.

The cost of activism is underscored by deeply personal losses. Unfinished rugs woven by her student Fereshteh, the early marriages of the girls she mentors, and the powers that be uniting to bring her down—all serve as reminders that the pursuit of change doesn’t come without sacrifice and hardships.

The film reaches its emotional apex in a scene of breathtaking liberation. Sara leads a group of young girls on motorcycles across the mountains, the open sky stretching endlessly above them while the soft, trembling notes of a setar underscore the moment. For the girls, who are still unmarried and constrained by societal expectations, this ride represents a fleeting, but profound taste of freedom, autonomy, and joy. The sequence contrasts sharply with earlier images of restriction, unfinished dreams, and personal sacrifices, highlighting the duality of rebellion: the immense cost it carries, and the rare, transformative moments it can create.

In this brief, exhilarating ride, the film celebrates both the courage of Sara and the possibility of empowerment even within rigidly conservative spaces. The scene is a visual embodiment of the metaphor, “cutting through rocks”, with the women on motorcycles cutting through the mountains of northwestern Iran.

Filmmaking and Cinematography

Khaki and Eyni spent seven years making Cutting Through Rocks, returning to Shahverdi’s village in eight separate production trips, each lasting 30–80 days. Their small, two-person core team allowed them to build deep trust—Khaki engaging women in private spaces, and Eyni (a native Azeri-Turkish speaker) navigating cultural sensitivities.

They also had to juggle bureaucratic permissions, skepticism from locals, and complex editing, combing through 200 hours of footage to shape their narrative. The very existence of the film is a testament to the passion and assiduity of the filmmakers to the project.

Eyni, who also serves as co-director, chose to shoot the film himself, avoiding a large crew to preserve trust and minimise intrusion. This decision allowed for the camera to feel like a quiet companion rather than an outsider. The team also used natural lighting throughout, giving the images an honest, unvarnished texture that mirrors the real-life struggles of Shahverdi and her community. Eyni mostly filmed on a Canon C70 with compact servo lenses, a setup that provided both mobility and cinematic quality while remaining unobtrusive.

Over the 7 years of shooting the film, the visual approach becomes deeply observational—Eyni staying at a respectful distance when needed and moving closer as relationships deepen, capturing spontaneous vérité moments that feel raw and emotionally grounded.

What emerges is a visual language that isn’t just aesthetic, but is charged with emotional weight, shaped by patience, trust, and a keen eye for the tensions of tradition, power, and change.

Feminism of A Different Kind

Cutting Through Rocks presents a form of feminism that is subtle, practical, and deeply rooted in local realities, rather than abstract ideology. Shahverdi’s activism doesn’t rely on slogans or formal politics, it emerges from everyday acts of resistance, like teaching girls to ride motorcycles or advocating for property rights and education. This feminism is relational and community-centered: it challenges patriarchal norms not by confrontation alone, but by opening spaces for choice, skill, and mobility. Through these actions, the film portrays empowerment as something lived and tangible, showing that feminist change can grow quietly but powerfully in spaces where regressive traditions are deeply entrenched.

Sara’s motorcycle becomes a literal and metaphorical tool for rebellion and reform. Through scenes of her teaching young girls to ride, the film shows the exhilaration and freedom of movement, juxtaposed with the village’s attempts to control and restrict them. The film also situates Sara within a larger context, evoking the resilience of Iranian women, from grassroots activists to the national mourning over Mahsa Amini.

Cutting Through Rocks is a completely different kind of world that holds a mirror to the usual narratives we’re accustomed to seeing. It illuminates struggles and forms of empowerment that rarely reach global audiences. Narratives like this are crucial because they expand our understanding of feminism, activism, and resilience beyond the familiar or urban-centric frameworks, showing that courage and change often flourish in the most unexpected and tightly constrained spaces.

Siddhant Vashistha is an independent journalist, based out of New Delhi, covering climate, culture, health and technology.