Summary of this article

This article examines girlhood through contemporary films

Several acclaimed films such as Girls Will Be Girls (2024), The Girlfriend (2025), Bad Girl (2025) and Inside Out (2015) & Inside Out 2 (2024) have been explored in this article amongst a few.

Themes of loneliness, desire, imagination and trauma are central to this article.

The very attempt to define the macrocosm of “girlhood” is like a cat pursuing a never-ending yarn of wool. To put things into perspective, girlhood can be articulated as the cumulative set of formative experiences that mark the transition into and the early contours of womanhood. Although now, it isn’t only limited to the experiences of the younger generations but has embraced mothers, aunts and grandmothers, who in many ways, tug onto their girlhood. While every individual traces a distinct path through adulthood, self-acceptance, ambition, sexuality, and interpersonal relationships, many aspects of girlhood remain inseparable from the collective trauma of growing up in a system fundamentally rigged against women.

And the worst part of it all is that one is too young to comprehend when exactly it has already begun and the inherent loneliness that comes with it. The labour of being a girl brings in its own set of gendered expectations, culminating in the idea of “being good”, which demands that she stay meek and compliant, look socially acceptable, work hard and stay ambitious, yet never form a worldview of her own—only exist within a bubble. The most significant loss across the spectrum of girlhood is the loss of innocence.

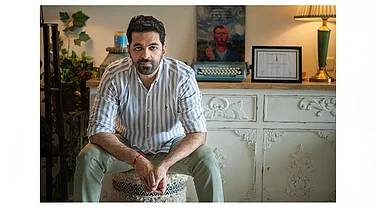

In The Girlfriend (2025), Rahul Ravindran presents the portrait of the archetypal sweet and polite girl Bhooma (Rashmika Mandanna), who falls prey to Vikram (Dheekshith Shetty), reflecting the struggles of many young girls unaware of the hidden costs of unequal romantic dynamics. For such men, a woman’s innocence is the most valuable currency. Her purity becomes a leeway into manipulating and shaping her into their ideal, stripping away her sense of self by isolating and controlling her to serve their own purpose.

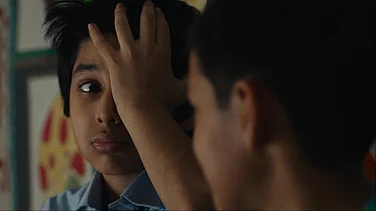

One might assume that projecting a certain politeness protects one from the aftermath of transgressions, like Mira (Preeti Panigrahi) from Girls Will Be Girls (2024). With her neatly cropped hair, flawless grades and modest above knee-length skirt, she fits the archetype of the ideal student. Yet, she is still subject to the objectification woven into her everyday life. Her curiosity about sex, relationships and gender discrimination turns into a painful lesson in self discovery and self preservation—one that comes at the cost of innocence. Shuchi Talati’s film is an excellent study on the Indian education system, wherein girls are taught to shoulder the burden of dignity and fear, conditioned to maintain distance from boys, while the responsibility of discipline falls disproportionately and almost exclusively on them.

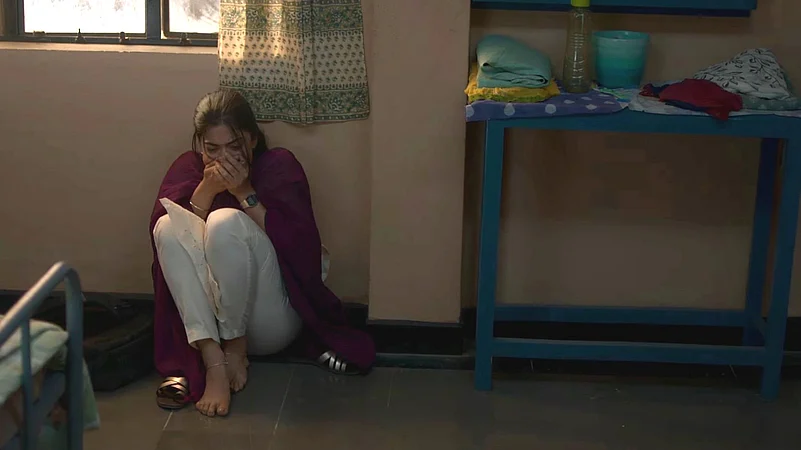

Contrastingly, in Bad Girl (2025), the title of the film itself folds into several layers of irony. The villainisation of Ramya (Anjali Sivaraman) and her process of simply growing up as a teenager—finding out who and what she likes, doing things she enjoys—becomes a balancing act entirely wrapped around rebellion. It starts as spite, a small rebellion to seize back a sense of control, yet soon evolves into an internalised defence mechanism against a world determined to erode a girl’s identity and ambitions.

Tiny acts of resistance define these stories—when Bhooma goes out for a girls’ night without checking in with her boyfriend, when Riley gathers the courage to leave her new home and return to where she came from, or when Mira dares to kiss Srinivas (Kesav Binoy Kiron) for the first time and steps out in her new skirt. In these films, the “good girl myth” emerges as a hoax that simply wants to keep women in check, mould them into submission and control them systematically (and generationally).

In a politically volatile environment that strips women of authority over both their interior and exterior worlds, films on girlhood focus on steadily turning the gaze inward to reclaim their selfhood. Instead of just framing girls as symbolic vehicles for societal anxieties, cinema now presents them as narrators of their own inner turbulence—desire, self-doubt, fantasy, and emotional intensity.

Bad Girl too, visualises Ramya’s childhood imaginings—filled with rainbows and freedom, as she eventually reclaims the love and home that finally liberates her. Inside Out (2015) and Inside Out 2 (2024) too, focused entirely and quite microscopically, on Riley’s experience of relocating from one city to another, negotiating the complexities of puberty, and learning to regulate emotions or confront mental-health challenges with nuance and sensitivity. Despite being marketed as a children’s film, it resonated with audiences of all ages because it offered a rare sense of comfort to the inner child in everyone, especially women.

A distinct segment of contemporary girlhood in films is now also shaped overwhelmingly by consumerist forces—skincare rituals, fast-fashion, influencer culture, and hyper-curated aesthetics. In such a landscape, girls are expected to keep up with ideals designed to be unattainable, while their insecurities are systematically monetised. Are You There God? It’s Me Margaret (2023) subtly critiques how girlhood is packaged as consumable through Margaret (Abby Ryder Fortson), as she and her friends compare themselves to magazine models, try on push-up bras, and navigate the swirl of teenage insecurities—nervous, yet eager to step into womanhood.

Again, in Bad Girl, Ramya is preoccupied with her facial acne for quite a prolonged period of time, searching up routines, dermatologists and expensive products, while realising how her youth has been stripped away by constantly overworking and not being able to sleep. While bodies of women remain a constant subject in films, it is also important for young girls to see their bodies as living, breathing, imperfectly human, worthy of honour in their own desires and needs.

Contemporary portrayals of girlhood now embrace female desire in all its messy and unpunished complexity. Films like the not-so-recent Aiyyaa (2012) unabashedly explored the internal world of Meenakshi (Rani Mukerji), flipping the gaze onto the man (Prithviraj Sukumaran) as the object of desire. Panigrahi in Girls Will Be Girls portrays the very vulnerable act of practicing her first kiss on her palm, or discovering how to masturbate. Sivaraman in Bad Girl too, projects a vivid imagination wherein she is free to feel and be with her lover—a wish she constantly attempts to negotiate with her reality at the cost of literally being labelled a cautionary tale. Her mischievous daydreams, lingering on the sweat on Nalan’s (Hridu Haroon) neck and the veins along his arms—offer a rare, refreshing glimpse of female sexuality. Vaidaangi Sharma’s debut short Kuchar (The Itch, 2025) emerges as a quietly radical tale exploring a teenager Chanda’s (Subhashree Sahoo) unexpected encounter with the big “O” and the quiet empowerment that comes from finally understanding what feels good on her own terms. This vibrant experimentation with portraying self-pleasure, yearning and negotiation reclaims self-discovery against the social surveillance that has long censored and sanitised young women’s inner worlds.

In Rita Heer’s Abja And Her Pickled Eggs (2025), the protagonist witnesses womanhood across the brief, glinting span of a life that’s barely her own. Whether cast as mothers, partners, or daughters, the film questions what it means to be stitched into roles we’re rarely allowed to outgrow.

Marriage or dating may promise romance, but many women protect their vulnerability—or guard their autonomy and hard-won quiet—too fiercely to gamble it away. And while discourse fixates on the “male loneliness epidemic,” a far more entrenched truth goes unmentioned: countless women are lonely inside their marriages, raising children, running households, and shouldering emotional labour solo.

While there are endless physical and emotional insecurities to deal with, one can’t deny how so much of girlhood is rooted in the act of self-preservation from men and the price women have paid for making any exceptions. Whatever is left of that beautiful period of blossoming is then spent in rebuilding, reclaiming and rejoicing all that you were able to accomplish, despite it all. Whether it is Ramya, Mira or Bhooma—they are consistently disappointed and manipulated by their partners, warping their perception of romance and at times being put in dangerous situations.

Adding to this debate—Agnes (Eva Victor) in Sorry, Baby (2025) endures sexual abuse by a senior professor and then navigates the far-reaching aftermath. The film traces how trauma reverberates through every part of her life, unsettling her sense of self, reshaping her understanding of grief, and even altering her relationship with ambition. To be wary of strangers and relatives alike is common courtesy, but where are women supposed to go when even their partners can’t be trusted as safe spaces? Girls Will Be Girls, Bad Girl & Sorry, Baby all return to a single idea—that real happiness lies in the refuge of female friendships, the quiet rebuilding of selfhood and fiercely protecting it with all your might.

A major part of reclaiming female camaraderie in these films also relies on reconciling with mothers with whom they don’t see eye to eye. The mother–daughter bond becomes a mirror: daughters grieving the unlived (or wasted) lives of their mothers, mothers projecting their ambitions onto daughters, and generationally passing down or inheriting the same.

Anila (Kani Kusruti) reflects the same “good-girl syndrome” that shapes Mira—a pattern she eventually defies. However, her rebellion leaves her fearful of her own daughter transgressing those boundaries. Ramya’s fraught relationship with her mother unfolds strikingly in Bad Girl, largely because it surpasses the confines of the screen. Sundari (Shanthi Priya) emerges as a disciplinarian shaped by patriarchal ideas of right and wrong; in trying to keep Ramya “good” and safe, she inadvertently calls her own image into question.

Across both films runs a shared grief—a recognition of how trauma and conditioning shape women differently, and how healing demands an unconditional love that allows them to meet again. On a separate tangent, Priya (Kuchar) finds a renewed sense of freedom through her daughter’s journey, reclaiming a relationship with her own sensual self. The film honours desire as a dignified and essential part of womanhood. Similarly, the shared girlhood between Margaret, her mother (Rachel McAdams) and grandmother (Kathy Bates) in Are You There God…also becomes an intergenerational coming-of-age thread that ultimately unites and liberates all three women. By now, it becomes evident that girlhood trickles down generationally and sometimes up. It refuses to sit neatly within an age bracket—instead becomes an enduring, tender architecture within womanhood itself.

Ultimately, these films remind us that rebellion rarely arrives as a dramatic rupture; it unfolds through small, uncertain ways that quietly shape girlhood as an emerging language in its own right. When cinema continually treats this terrain as a genuine emotional and political landscape, it comes closer to capturing the subtle, deeply felt truths young women learn long before they can name them.