Summary of this article

Through Kudiyattam’s ocular mastery, performers like Kapila Venu conjure entire universes—rivers, mountains, and multitudes of selves—using only breath, eyes, and abhinaya, collapsing the boundary between performer and audience in an exchange of shared seeing.

From Ravana’s ten arguing heads to the performer who disappears into her roles, the essay reflects on how art holds many consciousnesses within a single body, a feat that fiction writers might envy for its immediacy and embodied truth.

Moving from a childhood home in Madras to a destroyed ancestral house in Kutch—and to the obliterated homes of Gaza—the piece meditates on houses as cradles of memory, asking what becomes of identity and remembrance when those shelters are erased, and how grief seeks ritual, pilgrimage, and imagination as refuge.

I was talking with the Kudiyattam artist Kapila Venu recently about the magic of eyes. I had read how Kudiyattam performers could show with their eyes, a particular motion of flies falling into a fire and then flying back unhurt (sikhini salabham). I was stunned by the detail of it. That the need for such a gesture existed, that it could be conceptualised, taught and performed. Students of Kudiyattam must master how to bring vayu (breath) into their eyes, so they can become conduits of sorts. A performer can take hours to move an imaginary mountain on stage; can show how a river originates atop some far mountain, then widens in grith as it comes toward you, then thins as it travels off into the distance. All with zero tech, just abhinaya and ocular wizardry.

Kapila told me that one of her favourite scenes in the Ramayana is when Ravana sees Sita for the first time. Ten-headed Ravana in his flying chariot. Seeing this beautiful woman. Each of the 10 heads beginning to describe some aspect of her. The many heads then arguing between them. This kind of multiplicity contained in a single body, which then enables the audience to experience it, is the kind of skill a fiction writer could be deeply envious of. It’s an exchange of vision in real time. Do you see what I am making? Can you see it too?

When I watched Kapila later that evening on stage, I tried to find her—the person I had been talking to just a few hours earlier. But she was not there. Or rather, she was somewhere alongside the person(s) she was on stage. On stage, she and her percussionists had summoned a world with an oil lamp, a tiny curtain, and a wooden stool. Poof. Universe created. A space that was circular and infinite, of mythic time and present time. A boundary had been drawn between them and us, but it was a porous one, an invitation to cross over the threshold to meet.

***

For 35 years I have dreamed about the house I grew up in. The house with orange and black gates on Shafee Mohammed Road in Madras. The house still exists as far as I know. It has become an architect’s office. Perhaps the gulmohar tree that used to stand between the gates still drops its orange lanterns regularly, and the Punjab Women’s Association still shares a boundary wall, and you can still buy chocobars in the Okay Stores down the street. Perhaps the old city of Madras still exists under this present-city of Chennai, and whoever my family were in that house still exist under the layers of our now-older bodies that move through different houses.

“The house is a large cradle,” Gaston Bachelard writes, in The Poetics of Space. Our first universe, a place of shelter and dreaming. Thanks to the house, our memories have refuge. To dream of the house we were born in, Bachelard writes, is to participate in some kind of original warmth, the environment in which the protective beings live (assuming of course, that childhood was a place of warmth). Perhaps this is why my dreams carry me back to it.

What happens when houses are decimated as they have been in Gaza? What refuge do bodies or memories have when bombs rain down upon these cradles?

But what happens when houses are decimated as they have been in Gaza? What refuge do bodies or memories have when bombs rain down upon these cradles? What methods of retrieval will be available to Gazans when there are plans to build the Riviera of the Middle East upon the rubble of their homes?

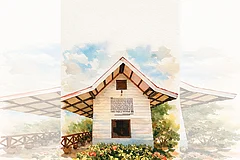

In February this year, I went in search of my great grandmother in Kutch, but the family house in Anjar, where my father’s family comes from, had been destroyed in the 2001 Bhuj earthquake. My great grandmother had died many years before, but as she had been resurrected in my imagination, the only way I could think of getting close to her was to make a pilgrimage back to the place of origin. I had last been there when I was eight. There were pictures of me with a pudding bowl haircut being taught to fold my hands at some kind of shrine. I found out later, this was our devasthana, and having arrived this far, I wanted to find this place. My relatives were either dead, had migrated, or were too distant to bother seeing me. After much pestering, I received a Google pin to the devasthana from my father’s cousin, which I followed. And there, in that hallowed space, where a photograph told me I had once been as a child, a tree rained yellow leaves upon me, I folded my hands and wept.

At some point in my mini breakdown, a man and his young daughter came to worship. The man asked if I was okay, and I muttered something about my family having come from here, of being overwhelmed by the emotion of return, of not knowing if I was even in the right place. He asked my name. I told him. Doshi, he said. This is you devasthana, your kuldevta. You are where you are meant to be.

Spaces can hold transitions and losses, they can activate prophecy. The yellow leaves falling, the benevolent stranger with his child—wasn’t that a pathway toward my great grandmother?

What does it mean to make an imagined space on stage or on the page? To take a single red brick on stage and call it altar? To put words on a page and call it stanza. Doesn’t stanza mean room, after all? I think of the poem as a kind of house. Title as doormat or threshold for the reader to cross over and enter. Language as furniture, architecture, homeland. To begin a novel with a house, and a person living inside this house, the thoughts inside that person’s head, the weather, the neighbours, the troubles, the triumphs, the way they move around the world. Isn’t that a little universe? Isn’t it an exchange of vision, a way of saying, Can you see it too?

Language lives inside us, and lest I have been speaking too much of the eyes, let me speak for the mouth, the ear. The writer and translator Sara Rai shared a beautiful story of a man she knew, an Awadhi scholar who had lived in Frankfurt for many years, who imagined that the doves came to his balcony and spoke to him

in Awadhi.

Imagination enables metamorphosis, and metamorphosis is what I’m after. Not just as a maker, but as a seeker, a spectator. All the disappeared and dormant things can be resurrected. More than ever, the spaces we imagine are areas of freedom amidst an incredible shrinking; are spaces of multiplicity, when we are constantly being hammered into little boxes. When I sit in a darkened theatre, or alone with a book, I want simply to be moved, transformed, for the possibility of something to reach into my underconsciousness and confirm how vast they are, these spaces we carry around with us.

This article appeared as ‘Imagined Spaces” in Outlook’s 30th anniversary issue ‘Where is Elsewhere?’ dated January 21st, 2025, which explores the subject of imagined spaces as tools of resistance and politics.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Tishani Doshi Is a writer and dancer. Her fifth collection of poems, Egrets, While War, is forthcoming internationally in 2026