Summary of this article

Fictional and artistic spaces—from Macondo and Malgudi to dystopias and utopias—are not escapist fantasies but social products that reflect history, power, oppression, and collective memory. Architecture, landscapes, and settings in art and literature become active characters that encode politics, identity, displacement, and resistance.

In an era marked by censorship, war, nationalism, ecological collapse, and loneliness, imagination becomes a radical act. Artists and writers construct “elsewheres” to question linear time, challenge authoritarian narratives, and offer alternate ways of belonging, dignity, and freedom when speech and debate are constrained.

Elsewhere is both refuge and rebellion—a place where history can be rewritten, wounds acknowledged, and futures reimagined. Through art installations like Parliament of Ghosts and symbolic spaces like Party is Elsewhere, imagination restores agency, bearing witness to loss while sustaining hope for reconciliation, love, and transformation.

“Imagination is an essential tool of political resistance. We need to imagine new worlds, new language, new ways of relating to each other. Because once imagination produces new imaginaries, then institutional change follows.

Yet invoking imagination in politics can make resistance sound fun or easy. It’s not. To imagine often connotes play, we associate it with folktales, storytelling, myth. These are crucial realms for lasting transformation.”

—Minna Salami, Nigerian-Finnish writer and theorist

A story can take place in a space not confined to the present but unfolding in the future, the past and other worlds. What goes on in constructing these worlds? How does the architecture of an imagined building or landscape reflect politics, society and us? Are dystopian spaces prophetic? Are utopias an extension of our dissatisfaction with the present? Is the present itself elsewhere? Do imagined places reflect the urge to belong and negotiate with modernity, as in Malgudi? Or is it an escape into magic, like Macondo created by writer and journalist Gabriel García Márquez in One Hundred Years of Solitude? Macondo, an allegorical construction, referred to civil war, isolation and imperialism. It symbolised the absurd everyday in Latin America where history was being erased, manipulated and coerced into becoming a tool for oppression.

The spaces of fiction become social products, expressions of our worldviews, a strange map where memory mixes with imagination to render a space not yet reachable, and yet a space which delivers us respite from our restlessness. The backdrop is a character in the narrative. A central one where acts of transition, prophecy and resistance are performed.

Home and dispossession are major themes of our times, as wars displace people and class divides widen. How do we speak of the nation state, fixed spaces and identity when censorship has become the order of the day? Talking is near impossible today, and thus we return to the pen: writers, our allies for this anniversary issue of Outlook, celebrating 30 years, to imagine.

There are many elsewheres.

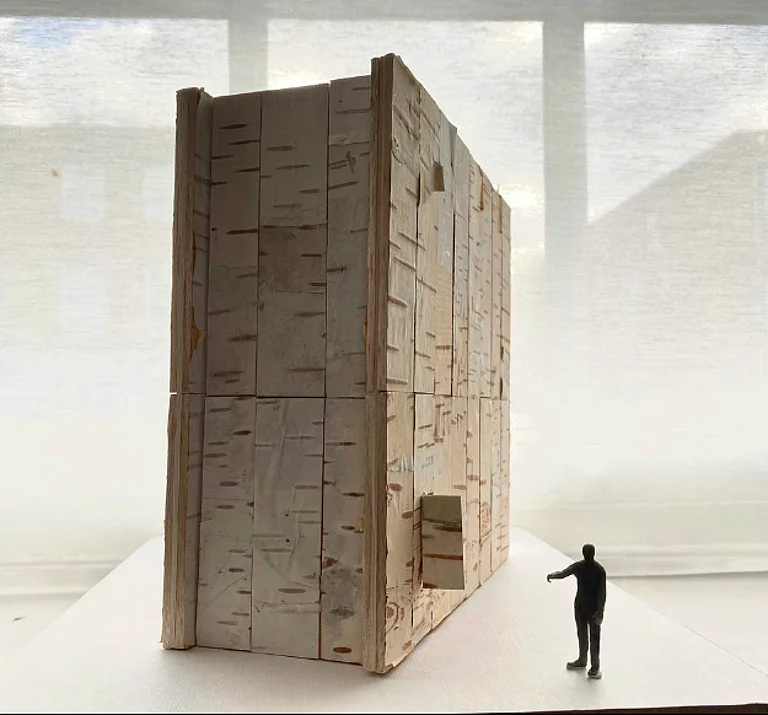

Like the 2019 art installation by the Ghanaian artist Ibrahim Mahama called Parliament of Ghosts, where he evoked the histories and memories of his countrymen in order to address the past and the present state of crisis and despair in his homeland with chairs, lockers and albums and reclaimed objects accumulated before Ghana’s independence in 1957. These objects became the witnesses. Mahama had wanted these seats to be occupied once again so everything could be debated.

“The parliament is a dense material history of colonial infrastructure, reflected back to us today. How can we use it to come to terms with our current economic and political conditions, in thinking about Brexit or the global crisis of migration?”

My homeland is my imagination.

That was the wall text hinting at the audacity of a reconciliantion with all that was wrong. Mahama’s elsewhere was a politically charged intervention, a place of hope. As all elsewheres are. They challenge the narrative arc of past-present-future linearity. A reorientation is always a possibility. Art offers that. Literature offers that.

The Anthropocene, the rise of fascist governments around the world, the endless wars, the political impotency at many home fronts, the many versions of glorified pasts and mythmaking to make people staunch nationalists, loneliness and lovelessness must all be countered with imagination that addresses the question of the unfulfilled promise of dignity and freedom and love. That itself offers hope.

There isn’t and must not be any ontological distinction between actual and possible worlds, between actual and possible time, between what’s real and what is not.

All worlds are possible. One has to imagine them first.

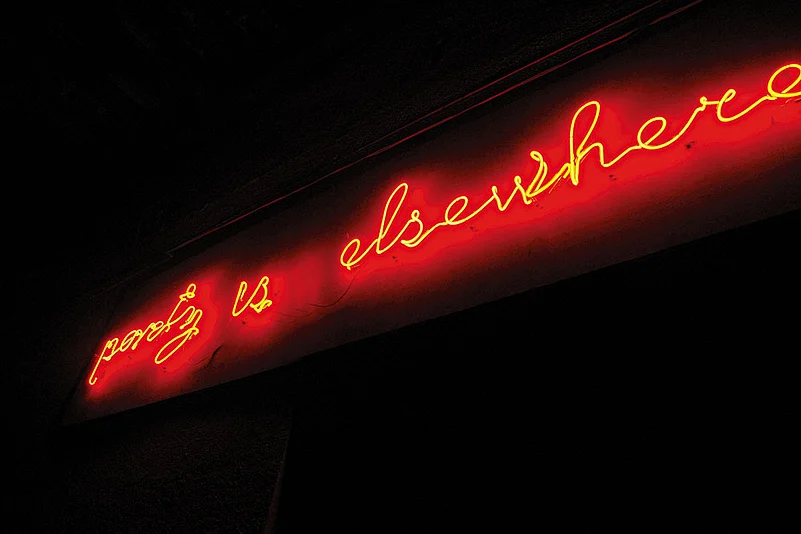

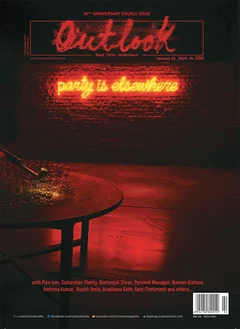

Like in that building where the neon sign ‘Party is Elsewhere’ blazed forth. Created by artist Sudarshan Shetty in 2005 in a building gutted by a fire in the same year, the space became the site of an imagined party, an absence, an inquiry, a desire, a wish, a place where all kinds of people entered hoping to find this elsewhere venue in another time, another space.

An image of that installation is the cover for this issue. It signals a promise and a refusal. Simultaneously.

In the pages of this issue, there are many such venues. Imagined and remembered. Homelands and hostlands.

My homeland is my imagination. In my imagination I have entered the rooms of my ancient house to edit the endings of the people who lived here many years ago to make them more bearable, to rewrite their stories as an act of resistance, an ode to their existence and their identity. They deserved more. That was my rebellion. To find the elsewhere place for myself and others who became a part of my story.

All these rooms contained worlds that crisscrossed memory with longing. Sentences were formed here, love was unleashed and grief formed cobwebs that let the spiders weave their circles as if a shaman was already at work conjuring spirits and keeping them captive within those abandoned homes. The spiders were always at work. The destruction during the day didn’t deter them from working at night on building their home again. But those stories are for another time.

There is a passage in the 2005 book The People of Paper by writer Salvador Plascencia where magic realism is used to deal with racial violence and anti-immigration policies in the context of Mexico and America, with love and loss and where monks make people out of paper. In this elsewhere space called El Monte where even the sky is made out of paper and here, they wage a war against Planet Saturn, who is yearning for his lover.

In the dedication page, Saturn writes: “And to Liz, who taught me that we are all of paper.”

There’s a another passage there.

“He folded the letter, stuffed it into an envelope, and affixed postage. Saturn did not know her zip code or apartment number or the city where she had gone. He put her name on the envelope. Below her name he described the types of places where she might be: cities with rivers, streets with breezes, apartments with steps, rooms with canopies.

Still, three weeks later, there was no reply— just an itemized bill from the Postmaster General requesting reimbursements for maps of cities and waterways, for wind-velocity meters, and for all the man-hours spent climbing steps and peering into strangers’ bedrooms.”

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

We dedicate this issue to those who venture into the elsewhere, to people made of paper and to those who imagine and dismantle entire worlds for the sake of love.