The life and words of G.N. Saibaba highlight the human cost of prolonged incarceration under terror laws, as he spent a decade in near-solitary confinement before being acquitted in 2024, only months before his death.

Through accounts of prisoners and former detainees like Umar Khalid, Sudha Bharadwaj, and Anand Teltumbde, the narrative underscores remembrance and writing as acts of resistance, solidarity, and the ongoing fight for dignity and freedom.

“You think of the crime attributed to me: I have lived for freedom, I have tried to find the voice of the voiceless and I have tried to find my voice. I wrote about them. I spoke about them, those my fellow beings who are not allowed to have a voice of their own for centuries. This is my crime. Degrading my body and mind is not simply removing humanity from me alone, it is an act of dehumanising our entire society; our civilizational existence.

I hope none of you should feel sympathetic to my condition. I don’t believe in sympathy, I only believe in solidarity. I intended to tell you my story only because I believe that it is also your story. Also, because I believe my freedom is your freedom.”

—G.N. Saibaba, Nagpur Central Jail, February 7, 2018, in his book Why Do You Fear My Way So Much? Poems and Letters from Prison.

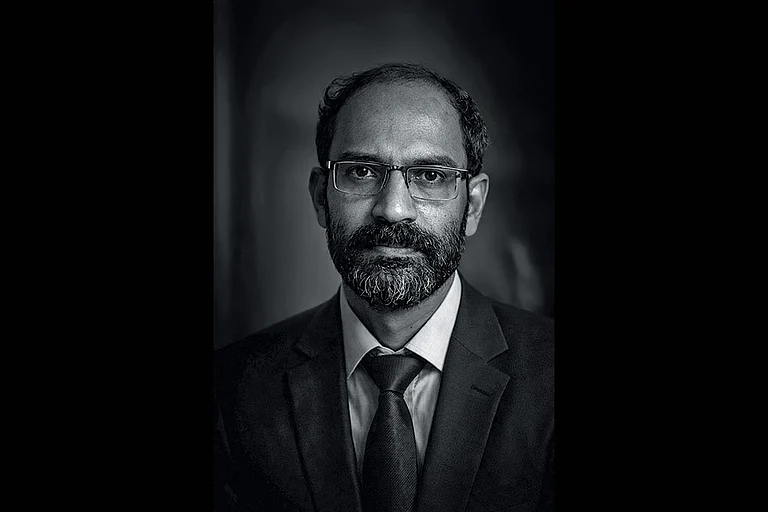

Whenever I see a wheelchair, I remember a man who was sentenced to a life term in 2017 by the Gadchiroli Sessions Court on allegations that he was a member of the banned Communist Party of India (Maoist) and its frontal organisation, the Revolutionary Democratic Front. The poet and the professor spent a decade in almost solitary confinement until he was acquitted in 2024. Gokarakonda Naga Saibaba, a professor at Delhi University, died in October of 2024 at the age of 57. Born into a peasant family in Amalapuram, Andhra Pradesh, he had been struck by polio in his childhood and was paralysed in his lower limbs.

The Nagpur bench of the Bombay High Court in 2024 acquitted the six accused in the alleged Maoist-links case under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA). A division bench of Justice Vinay Joshi and Justice Valmiki S.A. Menezes ruled that apart from “vague allegations” of conspiring to wage war against the government, no tangible material was found that would establish any “preparatory act” in the case. Journalists Prashant Rahi, Mahesh Tikri, Hem Keshwdatta Mishra and Vijay Nan Tikri were acquitted. The sixth person in the case, Pandu Narote, died in August 2022 in Nagpur Central Jail, awaiting this verdict. He was only 33 at the time. He died of fever.

Terror litigation in India is often long-drawn and vague. It is often unjust. It is always inhuman.

The wheelchair then is a reminder. Of a man’s fight for dignity. Not just his own but also of others he had chosen to fight for.

In January, Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam were denied bail for their alleged involvement in the 2020 Delhi riots. Khalid sent us a letter in 2021 from prison. Outlook published it. It was about hope and despair. It was about his life inside the prison. Again, he has talked about his life inside Tihar Jail and we are publishing it because one needs to be reminded of those who must not be forgotten. That’s the motive of this issue, the first in this year.

In January this year, I met Sudha Bharadwaj, a trade unionist, lawyer and human rights activist who was arrested in January 2018 along with 16 writers, scholars and activists under the UAPA in the Elgar Parishad-Bhima Koregaon case. After she was denied bail on three occasions, she was released in December 2021 on bail by the Bombay High Court.

She spent half of that time at Pune’s high-security Yerawada Central Jail in a block of cells once reserved for death row prisoners called the ‘Phansi Yard’ and wrote a memoir called From Phansi Yard: My Year with the Women of Yerawada.

“It feels so strange to be out of touch with political developments. I miss my trade union comrades, my lawyer colleagues; it’s almost like an ache. I long for news of how they are coping. My biggest purchase from the (prison) Canteen is always notebooks and pens. I meticulously make brief notes on the news items that interest me: news of workers’ struggles, talk of new labour codes; land and displacement issues, poverty and inequality; the latest judgments and gossip about courts and judges. And of course … anything and everything to do with my home state, Chhattisgarh.

Why? After all, I know I will never read those notes again. Perhaps it is my little act of protest, of stubbornness. To say no, I will not be cut off, I refuse to be cut off, my knowing all this still matters, I will live to fight another day,” she writes.

She, who is full of laughter and no bitterness, continues to fight for justice. Her bail conditions require her to live in Mumbai. Money is hard to come by. Her daughter is now a young woman.

I asked Bharadwaj if she ever worries for the future. She said she doesn’t.

I asked her why did she choose the tough life of fighting for the disenfranchised. She said it was an inheritance. Her mother, Krishna Bharadwaj, was an academic, and for the daughter, an IITian, it was never an odd thing to fight for her people.

“I fell in love with the landscape,” she told me about her days in Chhattisgarh.

Over cups of tea, she spoke about her life after her release. The 64-year-old’s laughter can crack open the many layers of fear.

A day later, I went to see Anand Teltumbde, 75, scholar and activist, at his residence in Dadar in Mumbai. Outside, police personnel stood as usual. Teltumbde was arrested in the Bhima-Koregaon case and released from Taloja Jail in 2022. He is a columnist with Outlook. He said he never thought he would come out of the prison.

It is the beginning of another year. And all beginnings must be marked. At Outlook, we mark it with testimonies from political prisoners about their lives after they got bail. It is a hard life.

We do what we must, what we can while we still can. We write.

Remembering is such an act. Writing is such an act.

While I read through prison memoirs, I came across a poem by Saibaba that he wrote on January 3, 2018, after he heard about the violent attack on the people who had gathered in the Koregaon-Bhima memorial near Pune to mark the 200th anniversary of the victory of Dalit soldiers against the army of the Peshwas in the battle of Koregaon in 1818.

“Patriotism can’t flow

through the diarrhoeal bowels

of demagogues

You can never understand

Koregaon’s heart of Bhima,” Saibaba wrote.

A wheelchair will forever remind me of Saibaba. Of freedom denied.

These are voices from the prisons and outside of them. Read.

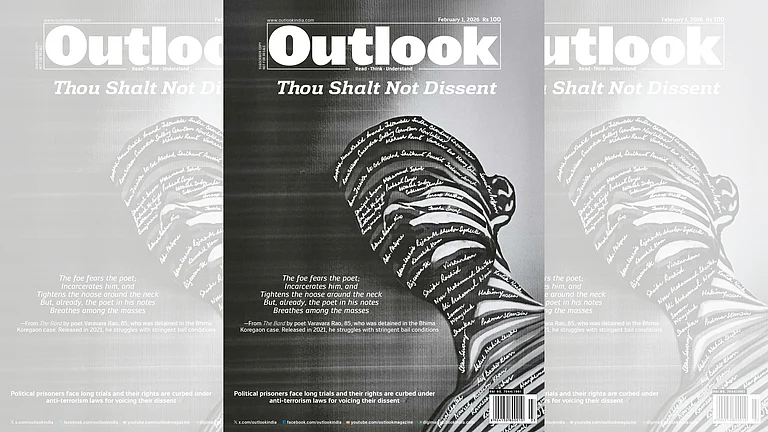

(This article is part of the Magazine issue titled Thou Shalt Not Dissent dated February 1, 2026, on political prisoners facing long trials and the curbing of their rights under anti-terrorism laws for voicing their dissent)