Summary of this article

At a Press Club discussion, women political prisoners and scholars traced incarceration as a long-standing, gendered reality shaped by class, patriarchy, and state power.

Speakers highlighted how women’s prisons mirror society outside, where children grow up behind bars, labour and care continue, and hope survives amid deprivation.

Prison diaries, they argued, reclaim women’s voices by documenting not just suffering, but life, solidarity, and resistance inside jail.

Incarceration in India is not an exception but a long-standing social reality, one that has shaped women’s lives across generations, from the years immediately after Independence to the present moment of prolonged undertrial detention. This was the central argument that emerged at a discussion on women’s prison writings held at the Press Club of India on Saturday evening.

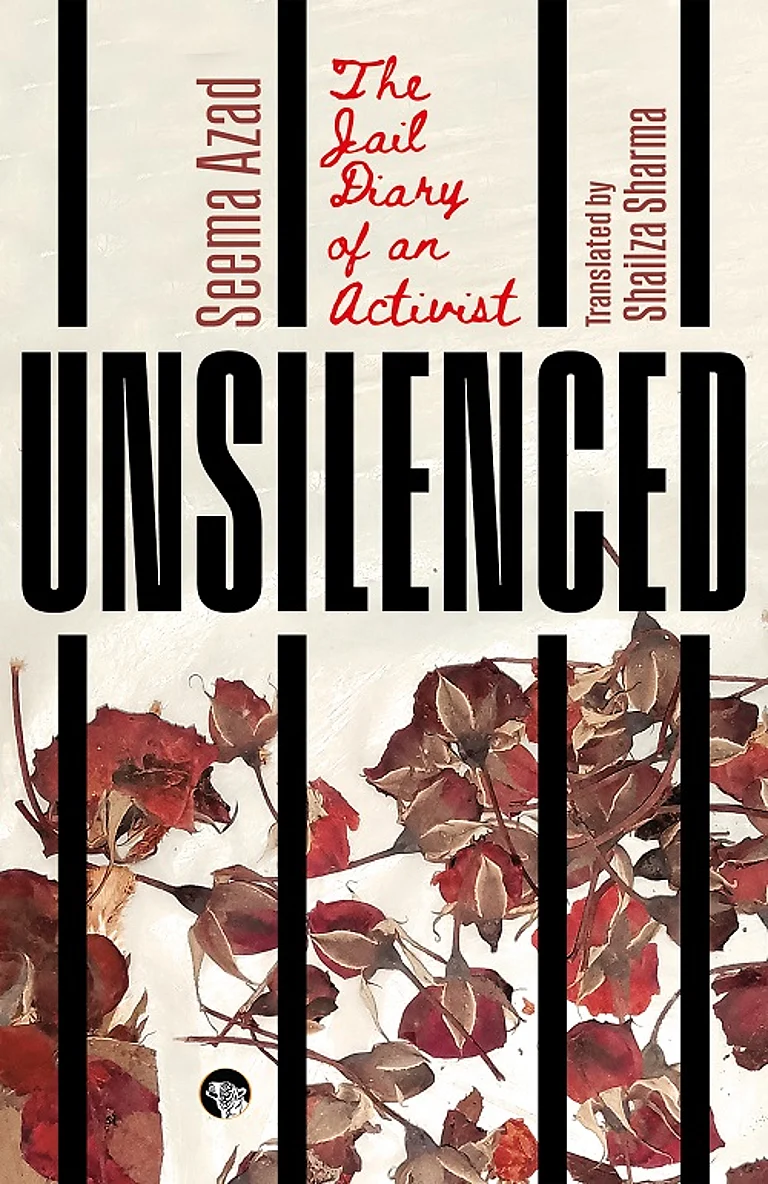

The conversation centred on two prison memoirs by women political prisoners, Unsilenced: The Jail Diary of an Activist by Seema Azad and Phansi Yard Se by Sudha Bharadwaj which brought together feminist historian Uma Chakravarti, activist-journalist Seema Azad, translator and legal scholar Shailza Sharma, and researcher Mary, among others.

Opening the discussion, Chakravarti placed women’s incarceration within a longer historical frame, recalling how she first became interested in prison narratives while researching state repression during the Emergency. “The incarceration system is quite old. We have always stood against it, regardless of which government was in power,” she said, noting that women’s experiences of jail remain deeply shaped by class, education, and caste.

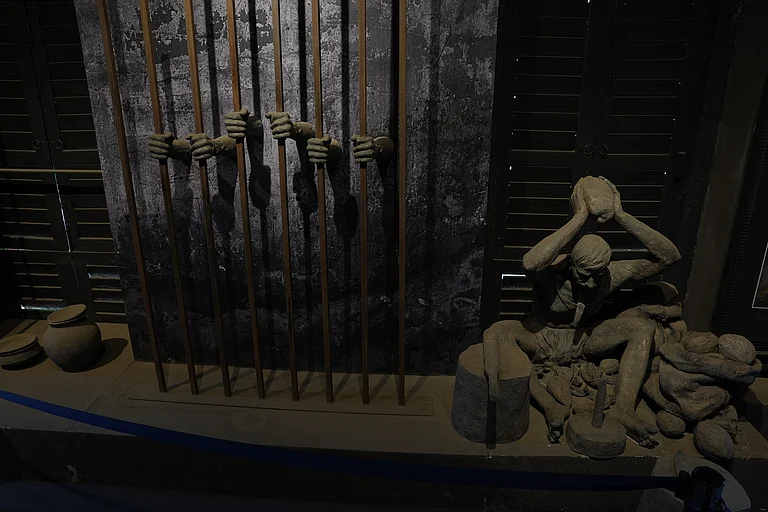

She recounted interviews conducted decades ago with freedom fighter Durga Bhabhi, whose imprisonment in the late 1940s revealed stark internal hierarchies within women’s jails. Educated women were placed in ‘B class’, while others were relegated to harsher ‘C class’ barracks, often located near mortuaries, where bodies were brought in at night. “That proximity to death was the most frightening part of her jail experience,” Chakravarti said, describing it as a memory that stayed outside official records but lived on as oral testimony.

Across decades, one theme remained constant: children growing up behind bars. Chakravarti recalled women prisoners describing how their children had never seen a rainbow, or mistook stars for distant lamps.

“The most moving aspect of women’s prisons is the presence of young children who inherit punishment without committing any crime,” she said.

Azad, who was arrested in 2010 and spent years in prison under charges that labelled her a “Maoist”, said she initially entered jail with fear, but emerged with a more complicated understanding. “What surprised me most was that jail is also a place where one can live,” she said. “Where there are people, there is life. And where there is women’s life, there is even more life”

Becoming Free Behind Bars

Azad described how imprisonment often gave women their first experience of individual recognition—being called by their own names in court, addressed directly by judges, and heard as independent persons rather than as wives or daughters. “For many women, jail becomes the first space where they recognise themselves as individuals,” she said

At the same time, she spoke candidly about the disturbing freedom jail sometimes offered women compared to their homes. Women, she said, laughed about being “free” from unpaid domestic labour—one inmate joked that confiscation of her husband’s clothes saved her from washing them every week. “It is astonishing and disturbing that a state prison can feel freer than home,” Azad said, calling it a blunt comment on patriarchy rather than a defence of incarceration.

Azad also reflected on the irony of being isolated in prison as a political prisoner, yet finding solidarity everywhere. Recipes improvised from scarce supplies, shared songs, handmade cards, and poetry became acts of resistance. “Jail is perhaps the place with the most hope,” she said. “I have not seen such intense hope anywhere else”

However, Azad disagreed with one oft-quoted idea from Bharadwaj’s prison diary—that only “cats and children are free in jail.” “Cats may be free,” she said, “but children are not. They are locked inside barracks at night and cannot see the sky”

The discussion also addressed how labels shape prison life. Mary spoke about Kashmiri women prisoners who enter jail already marked as “terrorists” by the state and media, often facing isolation from other inmates. “Jail becomes a different world altogether,” she said, where identity is forcibly merged into the logic of incarceration

Sharma highlighted how women’s prison writings document not just personal suffering but collective survival. Unlike heroic political narratives, these texts dwell on ordinary women, many imprisoned because of their husbands’ actions or because poverty denied them access to bail. “Men get bail faster. Women are left behind,” Sharma noted

One of the most quietly powerful presences at the event was Vishwavidya, Azad’s partner, who was jailed under the same charges. Azad described how shared reading, writing, and memory sustained them across separate barracks. Poetry, handmade cards, and letters circulated quietly, reminding them that intimacy could survive even in enforced separation.

As the evening closed, a question hung unresolved but urgent: are women in jail because of individual crimes or because patriarchy leaves them with no safe exit? Azad framed it bluntly: “If patriarchy were removed from society, not a single woman would be in jail”