Summary of this article

Sudha Bhardwaj describes repeated police visits to her residence, seemingly intended to intimidate her, despite her regular reporting to authorities.

She highlights the difficulties faced by women prisoners post-release, including lack of social and financial support.

Despite the obstacles, Bhardwaj is gradually rebuilding her life in Mumbai with support from friends, colleagues, and civil society.

A couple of weeks ago, cops in civil dress—or so they claimed to be—arrived in the society where I live in a friend’s accommodation on rent. The police have my mobile number, which, no doubt, they monitor regularly. Besides, I report to the local police station every 14 days, and I regularly attend court dates, at least once every 15 days, if not more frequently. Despite this, the police did not bother to call me.

When they arrived at my place, I was in my senior’s office in Fort, from where I practise in the High Court. They did not have any questions to ask. The police at the Kasturba Nagar Police Station, where I report, and the National Investigation Agency (NIA) officers, who attend our court dates, both convincingly pleaded innocence of this visit. So, clearly, this was only to scare off my neighbours, my society and no doubt any weak-kneed house owner. This has happened for the third time in the three years that I have been living here, and five or six times since my release in December 2021. The message is loud and clear—you may be trying to slowly rebuild a life broken by incarceration, but every now and then, we will turn up to muddy the waters, demonise you, scare your employer, your landlord, your neighbour; never forget, Big Brother is watching you.

Life after jail is tough. We are the luckier ones who have social capital—friends, family, other activists, our organisations, our contacts, our education, civil society—to stay afloat. Most women in jail, particularly those involved in crimes of passion— murder of a husband or mother-in-law or lover—are abandoned in jail for years together, and rehabilitation is really not taken seriously by the jail authorities. The skilling programmes—beauty parlour training or “housekeeping” (read jhadoo-pochcha)—are a joke. There is hardly any effort to help prisoners study the courses that they enrol in; they are absolutely on their own.

The social workers at the jails are always occupied juggling paperwork. In such a situation, bringing women prisoners in meaningful or regular contact with their estranged families and children takes a backseat. Women might be allowed to write to husbands or meet co-accused husbands during jail mulaqats. But lovers or friends … heavens above, unthinkable!

Often, women are not financially supported. They have to depend on a far-from-proactive legal aid system to even get bail. Sureties are extremely difficult to procure, particularly for prisoners from outside the state. Hence, many women languish in jail even after bail orders are passed. Mathurabai, an elderly Mang lady with comorbidities, died of Covid while in Byculla jail only because she could not afford Rs 15,000 for a cash bail she had got more than a year earlier.

No wonder then that the greatest help women prisoners get after jail is from the friends they make in jail. Those friendships of diverse and unlikely people thrown together are crucial to survival—nay, existence—in jail. It is these friends who might ask their lawyers to represent a prisoner who has no lawyer, lend money for a cash bail or even help them with a roof over their heads till the newly released prisoner finds her feet. Knowing that I am a lawyer, so many have reached out to me for advice with their cases, or to “talk to their lawyers”. It is also no wonder that sans support, these women might return to the same or different worlds of crime—sex work, drug couriers, petty theft—that give them temporary safe harbour. This is referred to as recidivism, but what efforts, if any, have the jails made to provide them with any other practical alternative?

As far as I am concerned, I cannot thank enough the socially aware acquaintances who came forward to stand surety for me, the friends who gave me shelter in their own homes or in homes of their ownership, the senior lawyer who gave me the space, the work that I could, once again, immerse myself in to regain my identity and dignity, and the many trade unions and workers who entrusted their cases to me and provided for my sustenance.

I have totally warmed up to Mumbai. The mills may be gone, but it is a working-class city at heart. In the long daily commutes from Borivali to Churchgate, one finds familiar hard-working faces to smile at. Otherwise, think of being confined in an unknown city with no home, no family, no job and no bank balance. It was a few friends and many, many well-wishers, who have now become friends. They saved me.

However, that can’t compensate for the sudden and painful shift from my life as a trade unionist-cum-human rights lawyer for more than three decades in Chhattisgarh. That is where my organisation—Chhattisgarh Mukti Morcha (Mazdoor Karyakarta Samiti)—is; where my lawyer-colleagues at Janhit are; where I have my best friends in the working-class bastis of Jamul and Dalli Rajhara, my brave clients from villages all over Chhattisgarh; and the many public-spirited individuals that I have come to know in these decades of work. I know and love Chhattisgarh—the forests, the factories, the language, the songs, the food, the festivals and the bastis. Even the smoke and dust, and the mines are familiar. Above all, the workers who have given me so much love and taught me everything that I know about life are there. They joke and say: “Didi, you have come out of a small jail and gone to the big jail of Mumbai”. Well, I need bail from Mumbai as well.

But let me not be ungrateful. I am enormously relieved that the separation from my only daughter, Maaysha, has ended. Though we are not always under the same roof—she first did her graduation at Bhilai and is now pursuing her post- graduation in Clinical Psychology in Kolkata—at least we can speak to each other every day or whenever we want, see each other on a video call and for as long as we like. There is no lady constable barking: “Ten minutes are over”.

My daughter suffered enormously due to my incarceration. Particularly during Covid. The trips to Pune or Mumbai were not frequent. Mulaqats involved all forms of red-tapism.

The letters she wrote to me—full of anguish, anger and bitterness—would affect me immensely. I had to prepare myself mentally before opening her letters. The delays were inordinate. Her letters would just lie in the jail there for a week or so before they were censored and passed on to me. Similarly, my replies—we were allowed one letter in 15 days—would lie around another week before they were posted. So, in effect, my words of comfort would reach a traumatised child only after a month.

With my bail, she feels more secure and happy. On rare occasions when I don’t answer her calls—only because my phone is on silent mode or being charged in another room—she panics. But yes, through all of that, she has been remarkably brave and is pursuing her goal of studying Psychology with determination—no small feat. Her education is my top priority at this point.

There is an elephant in the room—how to survive financially. Though I love teaching and have given five or six online guest lectures to law and social work students since my release on bail, I will never be offered a formal job. The best of legal aid NGOs couldn’t keep me on their rolls—they fear their FCRA would be revoked in a jiffy.

I am fortunate to be a lawyer, as I can practice independently. However, the eternal dilemma that every socially conscious lawyer faces persists—those who need you the most will probably be least able to pay you. But that’s a familiar tightrope walk from the Janhit days.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Life after jail goes on—commutes, cases, calls, clients, cops and cravings. There are good days—when a case goes right, when my daughter comes home, when a co-accused gets bail. But on bad days, depression weighs you down and it is difficult to get out of bed. On such days, I am reminded of this song—“Ae dil hai mushkil jeena yahan, zara hatke, zara bachke, yeh hai Bambai meri jan!”

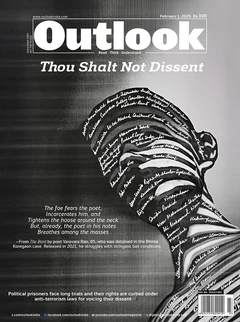

(This article is part of the Magazine issue titled Thou Shalt Not Dissent dated February 1, 2026, on political prisoners facing long trials and the curbing of their rights under anti-terrorism laws for voicing their dissent)