Summary of this article

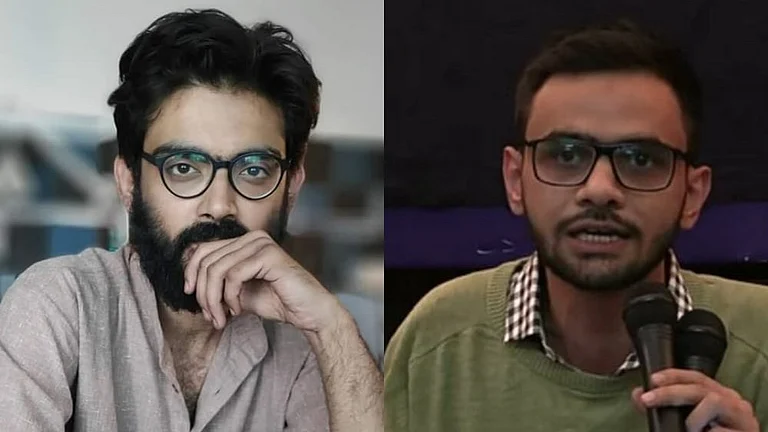

Granting bail to Arvind Dham in a case under the PMLA, an SC bench adopted a markedly different constitutional approach than in the case of Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam

If prolonged incarceration converts pre-trial detention into punishment in one case, why does it not do so in another?

When outcomes appear bench-dependent, legal certainty gives way to legal speculation.

A constitutional court draws its true strength from the consistency of its reasoning. When similar questions of law receive divergent answers within a short span of time, that legitimacy is inevitably tested. Jurists, legal scholars and senior members of the Bar have repeatedly voiced concern over a growing unease: that outcomes before the Supreme Court sometimes appear to turn less on settled constitutional doctrine and more on the composition of the bench. Though seldom articulated in formal terms, this perception is widely shared within legal circles and has become an unsettling undercurrent in constitutional discourse.

Two Days, Two Constitutional Realities

The inconsistency has surfaced time and again, but it came into sharpest focus in two judgments delivered on consecutive days recently.

On January 5, 2026, the Supreme Court declined to grant bail to activists Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam in cases arising out of the alleged “larger conspiracy” behind the February 2020 Delhi riots. The prosecution invoked the UAPA, arguing that the allegations implicated the sovereignty and integrity of the State. The Court held that prolonged incarceration, by itself, could not be a ground for bail in such cases.

“In prosecutions alleging offences which implicate the sovereignty, integrity, or security of the State, delay does not operate as a trump card that automatically displaces statutory restraint. Rather, delay serves as a trigger for heightened judicial scrutiny,” Court observed.

While the language acknowledged delay, it effectively subordinated the right to personal liberty to the statutory rigour of UAPA. The constitutional promise of a speedy trial under Article 21 was, in effect, placed in abeyance.

Contrast this with, just a day later, the Supreme Court’s judgment on January 6, 2026. Granting bail to Arvind Dham, former promoter of Amtek Auto Ltd, in a case under the PMLA, a bench comprising Justices Sanjay Kumar and Alok Aradhe adopted a markedly different constitutional approach. The Court observed, without qualification, that the right to a speedy trial applies irrespective of the nature or seriousness of the offence.

“The right to speedy trial, enshrined under Article 21 of the Constitution, is not eclipsed by the nature of the offence. Prolonged incarceration of an undertrial, without commencement or reasonable progress of trial, cannot be countenanced, as it has the effect of converting pre-trial detention into a form of punishment,” the court held.

Placed side by side, these judgments expose a fundamental contradiction. If Article 21 is not eclipsed by the nature of the offence, as held on January 6, how can it be effectively diluted on January 5? If prolonged incarceration converts pre-trial detention into punishment in one case, why does it not do so in another?

The Constitution does not recognise graded liberties. Article 21 does not protect some under-trials more than others, nor does it distinguish between political offences and economic offences. When courts do so implicitly, they risk creating a hierarchy of rights—one that finds no textual or moral support in constitutional law.

A Small Court, A Large Problem

What makes this inconsistency especially disquieting is the size of the institution itself. With a sanctioned strength of just 34 judges, the Supreme Court is not an amorphous body with hundreds of competing voices. One would reasonably expect a greater degree of doctrinal stability, particularly on questions as fundamental as personal liberty.

Instead, sharp divergences persist, often within short spans of time. This unpredictability leaves lower courts hesitant, encouraging a culture of denial over release. Bail, long described as the rule and jail as the exception, increasingly functions in reverse.

The cost of such inconsistency is not merely doctrinal confusion. It affects how lower courts decide bail applications, how investigating agencies conduct prosecutions, and how citizens perceive the fairness of the justice system. When outcomes appear bench-dependent, legal certainty gives way to legal speculation.

When Outcomes Appear Bench-Dependent

A palpable unease is taking root within the legal community, driven by the growing perception that outcomes before the Supreme Court increasingly turn on the composition of the bench rather than on settled constitutional doctrine. This anxiety is not unfounded. There have been notable instances where litigants have sought withdrawal of petitions, deferred hearings, or subtly recalibrated their legal strategies based on expectations of how a particular bench might view an issue.

Such conduct seldom finds reflection in formal court records, yet its widespread acknowledgement at the Bar speaks to a deeper and more unsettling institutional concern. When lawyers begin to anticipate results not by reference to precedent but by reading the bench, it signals a shift away from law-centred adjudication.

For a constitutional democracy, this is a troubling development. The authority of courts flows not merely from the written Constitution but from sustained public faith in their neutrality, consistency, and predictability. If outcomes are perceived as contingent shaped by who hears the case rather than what the law demands the rule of law itself stands diluted.

The Supreme Court stands at the apex of India’s constitutional structure. Its authority rests not only on its power but on the coherence of its voice. When two benches, within days, articulate fundamentally different understandings of Article 21, the problem is not merely one of interpretation, but it is one of institutional credibility.

Consistency does not mean uniformity of language; it means fidelity to constitutional principle. In matters of personal liberty, especially, the Court must speak clearly, coherently, and with one voice. Anything less risks reducing constitutional adjudication to a matter of judicial chance—a prospect deeply at odds with the rule of law.

(The author is a lawyer working as Judicial Clerk-cum-Research Assistant at J&K High Court)

The views expressed are personal