Summary of this article

India’s post-independence history shows repeated criminalisation of political dissent across movements and ideologies.

Laws like MISA, TADA, NSA, and UAPA have enabled prolonged incarceration, often targeting activists, academics, and minorities.

Cases from Annadurai to Stan Swamy illustrate a continuity in using incarceration as a tool of political control.

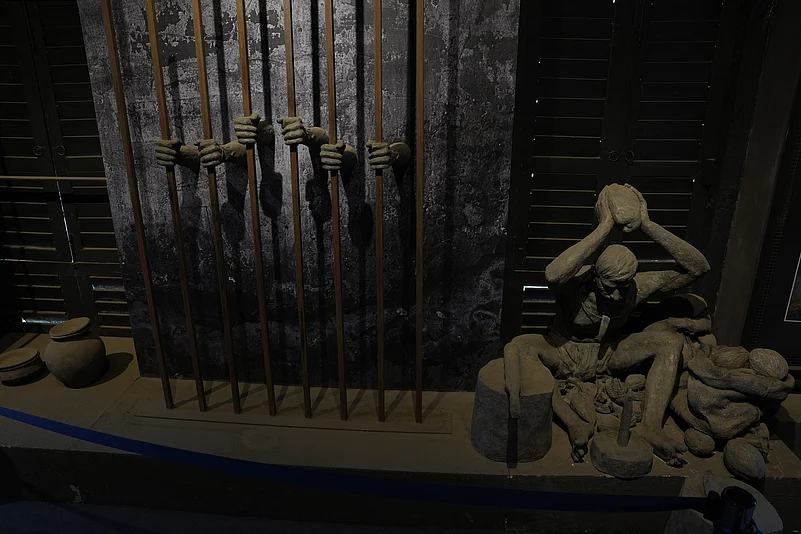

Across countries and political systems, incarceration has always been used as a tool to control the masses. It has been justified through shifting legal terms such as national security, public order, and counter-terrorism.

While the laws change, the logic remains the same. It has time and again proved that dissent against any government will be treated as a threat.

India’s post-Independence history reflects this pattern. Movements such as the Anti-Hindi agitations in Tamil Nadu in the 1960s, the emergence of the Naxalite movement in the early 1970s, mass arrests during the Emergency, the 1990s where the governments were made and broke like dominoes and the intensified targeting of minorities, students, activists, and political opponents after 2014 mark different moments of the same trajectory. Each phase has expanded the classification of the “political prisoner”, not reduced it.

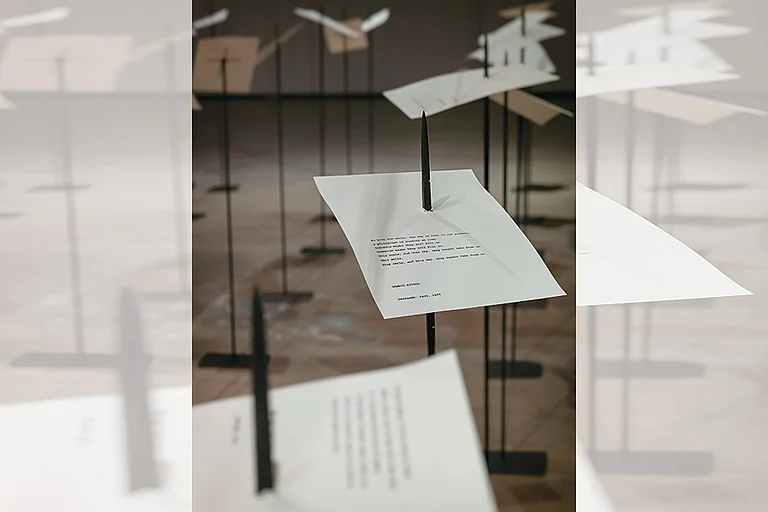

This timeline examines political prisoners charged under national security laws, including the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA) which was in force from 1971 to 1978, and later replaced by the National Security Act (NSA), and the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (TADA), operative between 1985 and 1995, which laid the groundwork for the present-day Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA).

These statutes have enabled prolonged detention, making the judicial process vague and giving way to the normalisation and criminalisation of political opposition.

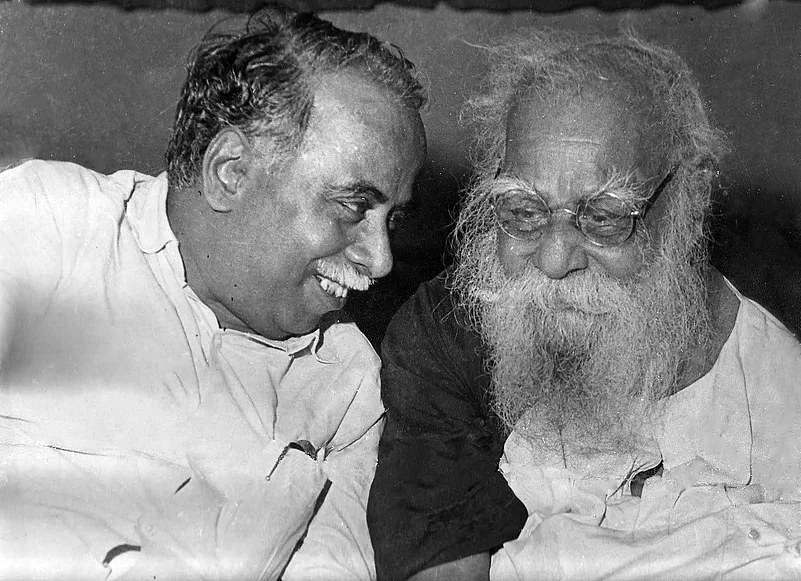

In the 1960s, political imprisonment was shaped by mass movements contesting the idea of cultural and linguistic uniformity. In Tamil Nadu, C.N. Annadurai, the founder of Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), had emerged as a central figure in the anti-Hindi movement, which framed linguistic autonomy as a democratic right.

At that time, under the Congress government, Annadurai was arrested multiple times. In November 1963, he was jailed along with around 500 DMK members for burning a portion of the Indian Constitution at an anti-Hindi conference, an act meant to symbolise resistance to linguistic centralisation.

He served six months in prison. Again, in January 1965, ahead of mass protests, Annadurai and around 3,000 DMK members were taken into preventive custody. These arrests demonstrated how the state treated mass political mobilisation itself as a law-and-order threat.

Behind this mobilisation stood Periyar E.V. Ramasamy and the Self-Respect Movement, which had long challenged Brahminism, caste hierarchy, and Hindi imposition. Periyar himself had been imprisoned in earlier phases of anti-Hindi agitations, establishing an early pattern in which ideological dissent was criminalised even in the absence of violence.

By the late 1960s, political imprisonment shifted sharply with the emergence of the Naxalite movement. The Indian state responded with arrests framed as action against “extremism” and “conspiracy.” Kanu Sanyal, one of the founders of the movement, was arrested in 1970 and remained imprisoned until 1977, spanning the years before and during the Emergency. His incarceration occurred under Congress governments at the Centre and in West Bengal. Even after his release, Sanyal was repeatedly jailed for political activism, including arrests as late as 2006, underscoring how radical left leaders were subjected to continuous surveillance and criminalisation.

Other radical left thinkers, including Azizul Haque, spent long years in prison through the 1970s and 1980s, Haque himself spending nearly 18 years incarcerated, often as an undertrial, for their association with the Naxalite–Marxist–Leninist movement that grew out of the 1967 Naxalbari uprising. Many reported torture and prolonged isolation.

Their imprisonment reflected a wider strategy of attrition: exhausting movements not only through encounters and bans, but through slow, grinding incarceration.

This repression reached its most explicit form during the Emergency (1975–77). Declared by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, the Emergency suspended civil liberties and normalised preventive detention on an unprecedented scale. The JP (Jayaprakash Narayan) movement, which had mobilised students, workers, and opposition parties against authoritarianism, corruption, and price rise, became the central target. Narayan, despite severe illness, was imprisoned. Tens of thousands of opposition leaders and activists were detained under the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA) and the Defence of India Rules (DIR).

Leaders who would later dominate post-Emergency politics — Morarji Desai, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, L.K. Advani, George Fernandes, and many socialists — were also jailed without trial. Fernandes was charged in the Baroda Dynamite Case, accused of conspiring to overthrow the state. The Emergency remains the clearest moment when political imprisonment was openly acknowledged as policy rather than denied as necessity.

After the Emergency, the Janata Party government came to power in 1977, formed largely by former political prisoners. Yet while MISA was repealed, the practice of incarcerating dissenters did not disappear. It mutated.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, the state increasingly relied on exceptional laws to suppress regional movements. In Assam, a Paresh Kalita aged only 12 was charged under TADA in 1991 for “inciting trouble against the State,” a charge that illustrated how the law’s broad definitions enabled arrests untethered from acts of violence.

In Kashmir, political imprisonment became systemic. Shabir Shah, a separatist leader and human rights activist, was arrested repeatedly throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, often under charges of sedition or alleged links to militancy. He spent a substantial part of his life in jail, frequently without conviction, reflecting how incarceration itself became a method of governing dissent in the region.

In the Northeast, dissent was contained through a different legal architecture. Irom Sharmila Chanu began her hunger strike in November 2000, demanding the repeal of the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA) after civilians were killed by security forces. Instead of engaging politically, the state arrested her repeatedly on charges of “attempted suicide.” She spent years in judicial custody in a hospital, force-fed through a nasal tube. Her incarceration, prolonged and medicalised, became a symbol of how protest itself could be criminalised.

The 2000s marked a decisive turn toward counter-insurgency framed as counter-terrorism. This led to Operation Green Hunt, launched around 2009–10 under the UPA government as a massive security offensive against Maoist insurgency across central India. While presented as a military operation, its political consequences were profound. Activists, lawyers, doctors, journalists, and researchers working in tribal areas were increasingly arrested as “Maoist sympathisers.”

Dr. Binayak Sen, a public health specialist and national Vice-President of PUCL, was arrested in May 2007 in Bilaspur, Chhattisgarh, under Congress rule. Charged with sedition and alleged links to jailed Maoist leader Narayan Sanyal, he was booked under UAPA and the Chhattisgarh Special Public Security Act. His work documenting human rights abuses during anti-Naxalite operations placed him squarely in the crosshairs of a state intolerant of scrutiny during Op. Green Hunt.

Around the same period, Arun Ferreira, a Mumbai-based activist working with marginalised communities, was arrested in 2007 on allegations of handling propaganda for the CPI (Maoist). He spent nearly seven years as an undertrial before being acquitted in 2014, a case that exposed how the process itself became punishment.

Others, such as Gour Chakraborty, a veteran left-wing activist and former spokesperson for the banned CPI (Maoist), were accused of “waging war against the state” under the UAPA. Arrested in June 2009 by Kolkata police, Chakraborty faced charges of membership in a terrorist organisation and abetting anti-state activities. He spent around seven years in jail as an undertrial, including time in Presidency Jail, while the case remained pending. In July 2016, he was acquitted due to insufficient evidence. His long incarceration, like many others, reflected a pattern of prolonged detention under severe laws before eventual exoneration, with lives left deeply affected.

Political imprisonment was not confined to the margins. In October 1990, during the Ram Rath Yatra, L.K. Advani was arrested under the National Security Act (NSA) by Bihar Chief Minister Lalu Prasad Yadav to prevent communal violence. Advani’s detention, brief though it was, remains a reminder that preventive detention has been used even against those who later wielded state power.

The 2010s saw the expansion of UAPA into a primary tool against dissent under the BJP-led NDA government. This period marked a shift from targeting armed movements to criminalising speech, association, and protest.

Following the 2019–20 protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, several student activists and scholars were arrested. Umar Khalid, a former JNU student leader associated with the anti-CAA movement, was arrested in September 2020 under UAPA in connection with the Delhi riots. Despite the absence of direct evidence linking him to violence, he has spent years in prison as an undertrial.

Sharjeel Imam, a doctoral student and public intellectual, was arrested in January 2020 on charges of sedition and later under UAPA, accused of making inflammatory speeches during protests. His incarceration marked a new phase in which political speech itself was framed as conspiracy.

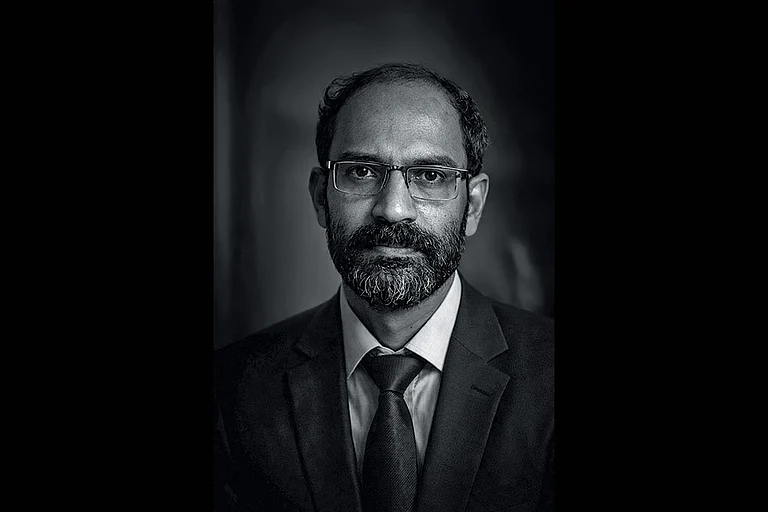

In July 2020, Hany Babu, an associate professor at Delhi University, was arrested in the Bhima Koregaon case under UAPA. A scholar of caste and labour movements, Babu was accused of links to Maoists based largely on electronic evidence. His arrest extended the Bhima Koregaon dragnet beyond activists to academics, reinforcing how intellectual engagement itself was being criminalised.

The most devastating outcome of this phase was the death of Father Stan Swamy, an 84-year-old Jesuit priest and tribal rights activist, arrested in October 2020 under UAPA in the same case. Despite suffering from Parkinson’s disease, he was denied bail and basic medical assistance. He died in judicial custody on July 5, 2021, without ever being convicted.

From Annadurai being jailed for burning the Constitution, to JP’s imprisonment during the Emergency, to the drawn-out suffering of undertrials under the UAPA, political imprisonment in India has long been a reality. It is not a one-off mistake but a repeated practice, shaped by laws, reinforced over time, and underpinned by the belief that persistent dissent must eventually be contained.