Summary of this article

Kappan was arrested on October 5, 2020, while reporting on a high-profile crime in Hathras

He endured inhumane conditions, including overcrowding, poor hygiene, inadequate food, disease, and neglect.

He was released on bail in February 2023 after 28 months, Kappan faced restricted movement, difficulty finding employment, and ongoing social stigma.

As the detainees rushed towards the van arranged to shift them from the makeshift quarantine prison to Mathura jail, I was suddenly reminded of a story I had once read about the concentration camps of Nazi Germany. When the Jews were ferried to the camps, the legend goes, many would rush to secure a seat by the side—just to catch one last, unobstructed glimpse of the world outside.

The memory came unbidden. And with it, a strange hardening within me. I felt myself grow indifferent, almost stoic, as if the moment demanded numbness more than grief. By then, I had completed 21 days at the makeshift prison—Phoolkatori School in Mathura.

I was arrested on my way to Hathras, where a Dalit woman had been brutally raped and killed. For more than 24 hours after my detention, I was kept in the dark, clueless about what lay ahead. Eventually, we were produced before a court and remanded.

As we were taken to the court, the journey felt unending. The vehicle sped through unfamiliar roads, the air thick with uncertainty. The police officers were indifferent, almost mechanical, while armed personnel sat around us in silence. The scene stirred memories of encounter killings—now normalised in many parts of the country. For a moment, I was convinced this was my final journey. I imagined the vehicle stopping in some abandoned stretch, imagined bullets ending the story abruptly.

I prayed. I thought of my ageing mother, my wife, and my children.

Only later did I understand that this was not an encounter in the making. It was something more drawn out, more calculated—prolonged incarceration meant to break me slowly, to reduce my life to suspicion, to brand me a terrorist, and to strip me of dignity, one day at a time.

The first thing the police and intelligence officers wanted to know was which CPIM Member of Parliament had asked me to go to Hathras. The question surfaced repeatedly, as if it were the only explanation they were willing to accept.

I had long sensed that my arrest was not about what I had done, but about who I was. My identity, my place of birth—these seemed to matter more than any facts. In that realisation lay an unspoken truth: my detention and prolonged incarceration were never random; they were preordained by prejudice.

It was only months later that I learned of the charges against me—a delay that, by itself, spoke volumes about the judicial system. Yet, on the day I was produced before the court, a policeman quietly passed on a message from a journalist in Delhi: a writ petition had been filed in the Supreme Court. In that moment of uncertainty, the news felt like a thin thread of hope.

Life in the makeshift jail at Mathura was unbearable. It was a school building hastily converted into a quarantine prison. We slept on sack sheets spread across the floor; there was nothing else. Mosquitoes hovered constantly, and sleep rarely came. People wandered through the classrooms—now cells—throughout the night, restless, exhausted, unable to lie still.

That was why many of us, myself included, longed to be shifted to Mathura jail. We did not know what awaited us there. All we knew was that anything seemed preferable to this slow, nightly erosion of the body and mind.

Sleep became a desperate pursuit. Some inmates tried to procure sleeping pills, anything to shut their eyes for a few hours. Skin diseases spread quickly. Worms crawled through the sack sheets the authorities had given us, and rashes, sores, and infections followed.

I could not bathe for three weeks during my detention there. The days merged into one another, marked not by time but by discomfort—by the slow, intimate ways in which the body begins to surrender when dignity is systematically denied.

I still remember one particular day. A jail employee walked into the classroom that served as our cell and played a news clip on an English-language channel. The visuals showed Congress leader Rahul Gandhi visiting my family in Kerala. In the midst of uncertainty and isolation, the sight brought an unexpected sense of relief. It told me that my family was not entirely alone—that the political society back home was watching, and caring.

My mother was old, burdened with the ailments of age, including dementia. When I was granted interim bail to visit her, I went with a heart heavy with pain. She did not recognise me. I pleaded with her silently, searching for a trace of memory that never came.

And yet, in that moment, I realised something unsettling. In extreme circumstances, we may wish that those we love were spared the full weight of reality. Had she recognised me, how would I have explained my incarceration? How would she have borne the knowledge that her son was accused of unspeakable things—of being part of terror networks conjured by the state?

That day, cruel as it sounds, her forgetfulness felt like an act of mercy. God, in his own way, was kind to both of us. She could not identify me, and therefore could not grasp the burden of the accusations that now defined my life.

No rules and guidelines were followed in my arrest. Even my wife knew about the arrest after the news broke on television. The Kerala Union of Working Journalists filed a habeas corpus petition in the Supreme Court. But contrary to the accepted norm, here, too, the petition was inordinately delayed. Normally, habeas corpus petitions used to be disposed of in seven days. But for me, it took seven months for the Supreme Court to take up the petition, which then directed me to approach the lower court for bail.

My case was first transferred to the Crime Branch and later to the Special Task Force. At the time, I knew nothing of these developments. Information reached me only in fragments—through jail employees, through scraps of conversation, through the occasional newspaper clipping that found its way into my hands.

When I was taken from the jail to the Special Task Force office, television cameras and YouTubers were waiting. Some shouted questions; others performed outrage for their viewers, enthusiastically portraying me and the others as terrorists. I watched it all from a distance, as if it were happening to someone else. A strange indifference settled over me—quiet, heavy, and unmoving—shielding me from the noise that sought to define me.

I remember one inmate telling me about the Special Task Force and its reputation for dealing with those it arrested. I listened, said nothing, and prayed. Prayer, by then, had become less an act of faith than a reflex.

The jail—and the treatment meted out to the accused—felt as though it belonged to another age, one in which the rule of law did not exist. We were forced to eat whatever was served to us, even when the food was contaminated, even when insects crawled through it. Complaints were not met with correction, but with punishment.

Once, a fellow inmate found insects in his food and protested. The authorities responded swiftly—not by addressing the problem, but by forcing all of us, myself included, to help with the cooking. It was discipline masquerading as order, humiliation passed off as procedure.

After I contracted the coronavirus, I was admitted to a nearby medical college. The atmosphere there was worse than the jail. Prejudice against those who were arrested was open and unrestrained. I felt it in the looks, in the tone, in the neglect. All I could do was pray—not merely for the strength to endure the hostility, but for the grace to preserve my belief in humanity itself.

I was arrested on October 5, 2020, and released on bail on February 2, 2023. No one knows when the trial will meaningfully begin, or when it will end. Those 28 months in jail were spent under a system where the whims and fancies of those in power prevailed. The rule of law was absent; humanity, even more so.

When I was finally released on bail, a barrage of reporters was waiting outside the jail, despite it being Budget Day. I had spent 14 months incarcerated in Lucknow jail. As part of the bail conditions, I was required to stay in Delhi for 45 days and report every Monday at the Nizamuddin police station.

Finding a place to stay was difficult at first; no landlord was willing to rent a room to someone accused under the UAPA. Eventually, with the support of journalist friends and various civil society groups, I managed to find accommodation. Those 45 days felt like a form of house arrest. I was not allowed to move beyond the limits of the police station’s jurisdiction.

After the mandatory period, I returned to Kerala. While I did not face open hostility from the public, a few YouTubers and habitual hate-mongers continue to trail me, attempting to stigmatise me as a terrorist. They are few in number. By and large, the public and political leaders have been sympathetic.

That said, I have not been able to secure regular employment since my release. With the support of a few kind-hearted editors, I have been freelancing, and that is how I manage to make a living now.

There are still many who believe that there is no smoke without fire, who continue to cast aspersions on me. I have learned to live with that suspicion. Yet, when I look back, beyond the humiliation and the suffering, two moments remain luminous.

One was a neighbour who asked my wife for ten rupees. She wanted to offer it at a nearby temple in Kerala, she said, praying for my safety. The other was another neighbour who rushed to our house when I returned briefly on interim bail, carrying a bag of dried fruits. She believed the dried fruits would last until I was finally released and came home for good.

It was through such small, unrecorded acts of kindness that I survived. Through the ill-fated arrest, the long incarceration, and the quiet erosion of dignity, these gestures kept me afloat. In years marked by darkness and inhumanity, it was these moments of grace—from familiar faces and strangers across the world—that brightened my soul and cemented my faith in humanity.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

(As told to N.K. Bhoopesh)

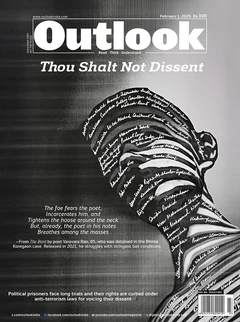

(This article is part of the Magazine issue titled Thou Shalt Not Dissent dated February 1, 2026, on political prisoners facing long trials and the curbing of their rights under anti-terrorism laws for voicing their dissent)