Summary of this article

The author says his critical reporting in Bastar put him on the police radar, leading to threats and false cases.

He describes being illegally arrested, jailed for months, and later pushed out of journalism.

He argues his story reflects how journalists are silenced for speaking the truth.

I’m among the few journalists who have consistently worked in Dantewada (in the Bastar region of Chhattisgarh). Around 2015-2016, I used to work for the Patrika newspaper and ETV Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. My reporting from the tribal areas of Chhattisgarh has been known for highlighting sensitive issues such as Naxalism, police action, human rights violations and corruption.

The most famous of my reports, ‘Jhoothe Hain Police Ke Bayaan: Modenar’ (The Police’s Statements are Lies: Modenar) was published in April 2015, for which I had asked some challenging questions to the then serving I.G., S.R.P. Kalluri, in a press conference. While other journalists would keep silent or simply receive the handouts given by the police, I raised serious questions regarding transparency within police operations. For this reason, I came on the police’s radar.

Kalluri had said, “I will see you”, implying it as a threat. I was issued repeated threats thereafter. Some false and minor charges (such as forgery and fraud) had already been slapped on me, on which no action had been taken for years. I had been demanding a law for the security of journalists and was active on the WhatsApp group called ‘Bastar News’. During Kalluri’s tenure as I.G., I was accused of tapping journalists’ phones and of sending informants in core Naxal areas in the guise of journalists by giving them journalists’ IDs. It was alleged that I had thus endangered the journalists’ lives from both sides, that is, that of the police as well as the Naxals.

On the evening of March 21, 2016, I was picked up by policemen in plainclothes while parking my car outside my office, without any reason being stated or warrant being issued. Without procedure, what they did was practically ‘abduction’. Several other journalists and human rights organisations called this arrest illegal too. It was alleged that I had sent an ‘indecent’ message on WhatsApp, where I had said that certain journalists were ‘seated in Mama’s (maternal uncle’s) lap’, by which I allegedly implied that those journalists sided with the police and opposed the proposed law for the journalists’ security.

Along with the sections 67 and 67 A of the IT Act (circulating indecent content in electronic format), and section 292 of the IPC, the police added another three-four pending cases to the list of charges against me. I was kept all night long in the Parpa police station in another district, Jagdalpur, 80 kilometres away from Dantewada. My bail plea was rejected during the court hearing. I remained imprisoned in Jagdalpur for approximately the next three months (96 days). I was lodged with prisoners such as Naxals and rapists and meted out inhuman treatment.

Around June-July 2016, after a difficult legal battle, and a lot of pressure from international human rights organisations (such as Amnesty International, Front Line Defenders and the Committee to Protect Journalists), I was finally granted bail. My case in the High Court at Bilaspur was represented by well-known advocates Kishor Narayan and Rajni Soren, and in the District and Sessions Court, Dantewada, by advocate Kshitij Dubey.

After I was released from prison, I was dismissed from my positions at both Patrika and ETV Chhattisgarh and was left unemployed. I had to repeatedly face court cases. My family’s financial state deteriorated.

Due to the repressive journalistic atmosphere in Bastar, many journalists were compelled to remain silent, flee the region or go to jail. Some local journalists and associates of the police targeted me, calling me ‘anti-national’. My arrest led to a nationwide and even international controversy on the security of the journalists operating in the Bastar region. Till date, many journalists in the region have either gone silent or are operating in the shadows of fear.

It is the work that a few of us have been doing that has acted as a ray of light in the surrounding darkness. My story bears witness to the fact that the cost of speaking out the truth is at times imprisonment, defamation or even death; nonetheless, the courageous are not silenced by these challenges. Though I tried to continue reporting in the similar fearless and candid way, I was eventually marginalised.

My story became a symbol of the struggles for journalistic integrity in the Bastar region, and the freedom of expression in tribal areas. Demoralised by the contemporary downturn in journalistic ethics, I decided to leave journalism for good and to start my own business. Currently, I run a computer shop in Dantewada to support my family.

My story has become a reminder of the steep price of portraying the truth in a sensitive region like Bastar. Trapped between the Naxals on one side and the might of the state and the police on the other, the local journalists continue to struggle. Many other journalists like me have also paid dearly for portraying the truth in Bastar before the rest of the world.

What happened to me in Bastar is a salient, yet painful incident within the history of Indian journalism. I want these incidents to be remembered as a tale of courage, repression, the bitter experience of incarceration and unrelenting hope. This battle is not just mine as an individual, but of the very right to freely speak out the truth in Bastar. It shows how sincere journalists in these sensitive regions are suppressed through such attempts as threats, false cases and imprisonment. In this very battle, I lost my dear friend Mukesh Chandrakar, with whom I shared a brotherly bond. Chandrakar was murdered by a local contractor and his brothers, associated with road construction. Later, his corpse was recovered from a septic tank within the contractor’s enclosure.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

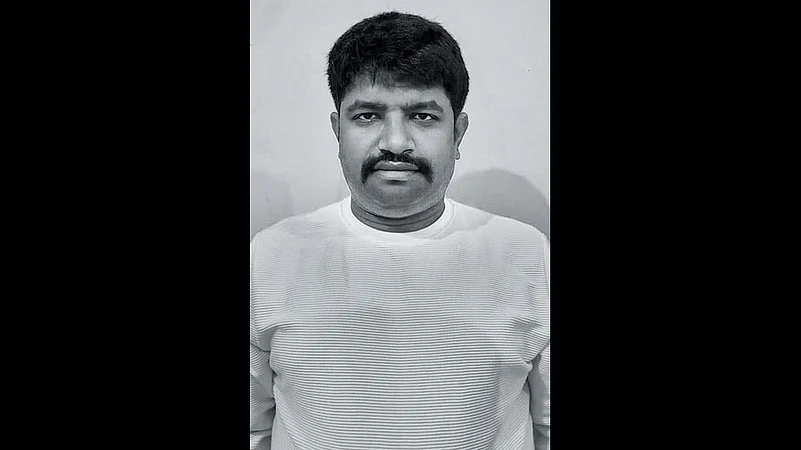

Prabhat Singh is a journalist who has reported on police brutality in Dantewada, Chhattisgarh. He was picked up on March 21, 2016, and was granted bail three months later.

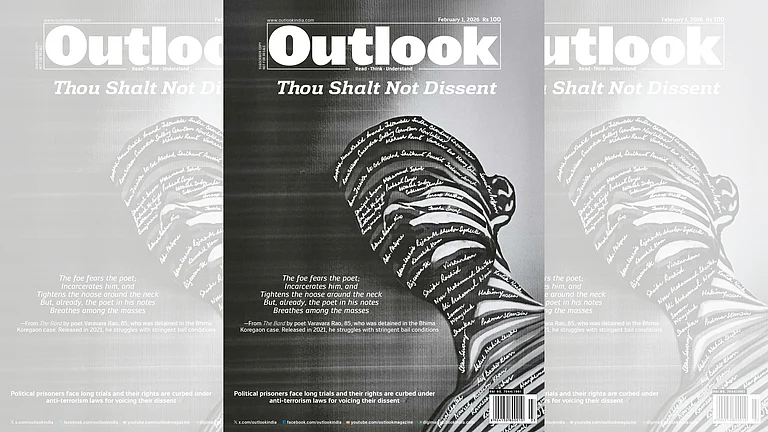

This article is part of the Magazine issue titled Thou Shalt Not Dissent dated February 1, 2026, on political prisoners facing long trials and the curbing of their rights under anti-terrorism laws for voicing their dissent.

(Views expressed are personal)