Summary of this article

Jail is full of absurdity and strange routines, which Anand Teltumbde notices and often finds darkly funny.

He writes his first lesson in a new epistemology was that facts are optional and seriousness is compulsory

Teltumbde notes that he believed such a spectacle would provoke outrage, or at least curiosity. It did neither

The tragic dimension of jail has been exhaustively mined. What remains scandalously underexplored is its comic genius. Prison is a factory of absurdity, running at full capacity every day, and I made it a habit to collect its specimens—especially during the so-called free hours, when the cells were opened each morning. This ritual began with the ceremonial clanking of batons, as guards slid them menacingly across steel bars, producing a sound—less like an alarm than a declaration of sovereignty.

One question haunted me: why did they always come in twos and threes? One guard was more than sufficient to shout “eh utha re” (hey, wake up) and scrape his baton against the bars with adequate hostility. The second appeared entirely ornamental—authority’s decorative surplus.

I once asked a guard why this redundancy was necessary. He replied instantly, as if citing scripture: “Roster duty”. I clarified that I wasn’t asking what he was doing—I could see that—but why it required two people. This introduced an unwelcome philosophical turn. After a pause, he deployed the most powerful incantation in the prison universe: “Sayabale vicharato”—we’ll ask the saheb.

Inside jail, sayabale vicharato is not a promise but a destination, where questions are deposited and never retrieved. It absolves guards of thought, sahebs of answers, and the system of explanation. Authority, like the morning wake-up call, arrives in pairs—not because it must, but because it always has. The weekly rounds were a culmination of this comedy!

In my solitary moments in the cell, recalling such comic instances became a private pastime.

I remember clearly being implicated in the Bhima Koregaon case—its comic quality. When the Pune police held a press conference on documents allegedly recovered from seized electronic devices of the first five arrestees, they announced—almost with relish—that the conspiracy had widened. As if rehearsed, a journalist asked for names. Mine appeared instantly, with the confidence of a magician producing a rabbit from an empty hat.

Moments later, the police read aloud, with ritual solemnity, a letter supposedly written by someone they had already certified as a Maoist operative. The letter addressed to ‘Anand’ which surely had to be me—stated that a seminar I attended at the American University of Paris had been funded by his party. It was oddly moving to learn that my academic life had been generously sponsored without my knowledge. I felt like a beneficiary of a secret scholarship run by the underground.

The police’s imagination could not travel beyond familiar terrain. In their universe, everything has a price. An academic seminar must have a sponsor; a sponsor must have an agenda; and, an agenda must be a conspiracy. That universities invite scholars to speak was an unnecessary abstraction. This American university was an accomplice of Maoists in India in disguise!

The inconsistencies were so blatant that I laughed as the officer read the letter with grave expressions, as though truth were produced by seriousness rather than coherence. It was my first lesson in a new epistemology: facts are optional; seriousness is compulsory. Later, in a rare moment of discretion, the High Court reprimanded this high-ranked police officer for addressing the press before submitting evidence to the court. Alas, the court did not know that the officer had not only read the letters, but had also distributed them to journalists like pamphlets. I could not resist laughing when a journalist friend from a TV channel mailed them to me in a bunch.

When the story appeared in the chargesheet, a lawyer friend warned me that this was no laughing matter. The chargesheet was brimming with many more fictional subplots. In my innocence, I assumed that once it reached a court, it would fall flat. Instead, during the hearing, the police slipped something into a sealed envelope, and my bail application was struck down. The same ritual was repeated in the apex court. That was when it dawned on me that this was not an error in procedure but the procedure itself.

Alarmed, I wrote an appeal to the people of India—My hopes lie shattered; I need your support. I even designed a “do-it-yourself” template to help citizens assess their own likelihood of landing in jail. It was meant as dark humour, but it doubled as a user manual for modern citizenship.

The template went something like this: one fine day, regardless of your social standing—or lack of it—you discover that the police of some “S” state have named you a terrorist. While investigating some crime, they recovered a letter addressed to “X”, whom they identify as you, from the computer of someone, at a place “Z” you have never visited. The letter was written by “Y”, identified as a member of a banned organisation, stating that you were present at location “P”, which you may not even have heard of. This is corroborated by a witness who heard someone say they saw you there with someone else identified as known to “Y”. Now, replace the variables with anything you like, and congratulations—you are now charged under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA). You lose your job, your family loses peace, you are defamed, friendships evaporate, and life is reduced to a long legal footnote. Taken together, it can feel worse than death—at least death has the courtesy of finality.

I believed such a spectacle would provoke outrage, or at least curiosity. It did neither. In my cell, I often recalled my appeal and laughed quietly at my own naivety. The people of India, I realised, were far too seasoned to be disturbed by such minor inconveniences. In a country where absurdity is institutionalised, tragedy must learn to be funny just to be noticed.

My first round of petitions ended with the Supreme Court rejecting my quashing application, while graciously granting me one month to seek anticipatory bail from an “appropriate” court—judicial compassion in its minimalist form. Thus began my second round, starting from the lowest rung: the Pune court where the case had originated.

Around this time, I was invited to Thrissur as chief guest at a meeting attended by senior serving and retired government officers. It was a mildly ironic role, though irony was fast becoming my permanent residence. On my way to Kochi airport, I learnt that my application had been rejected. By then, rejection had become familiar; I accepted it calmly.

At the airport, on impulse, I chose one of the two tickets I was holding—one to Goa, the other to Mumbai—and landed in Mumbai around 2 a.m. As I stepped out, two policemen appeared from behind and escorted me to the airport police station. I cautioned them that they were acting illegally, since I was still under the Supreme Court’s protection. They replied that they were following the orders of their saheb—a principle that trumped constitutional safeguards. Initially, they denied me my phone, later allowing it so I could inform my wife—who was expecting me home—that I had been arrested instead.

She arrived with her brother, the way families arrive at police stations. Soon the Pune police turned up and completed the paperwork like a routine errand. One officer checked my bag for a laptop. It was right on top, but he pronounced it an iPad and moved on. I laughed inwardly at this triumph of technological classification. They let my wife take my phone and bag, placed me in their rickety vehicle, and drove me to Pune.

The 13 hours I spent in the filthy police lockup became the most practical lesson I have ever received on Article 21—the right to live with dignity. No textbook or constitutional bench could have prepared me better. I was also initiated into the grammar of crime through a brief acquaintance with an extortionist, who explained it succinctly: money can buy anything, unless a Big Boss has taken interest in you. He shouted at the police; they responded with restraint, lubricated by cash.

The lockup doubled as an orientation programme. It introduced me, in condensed form, to what awaited me in Taloja Central Jail, where I would squander 31 months of my life. In those 13 hours, the Constitution revealed itself not as a shield but as a slogan—recited respectfully outside, suspended efficiently inside.

Those hours previewed the prison curriculum: infinite humiliation; food that barely qualified as food; toilets without shutters; endurance in unhygienic surroundings; and life under constant stress, cut off from the world during a pandemic administered with bureaucratic sadism.

In retrospect, the lockup functioned exactly as it should have—not as an aberration, but as a sampler. It taught me that dignity, like freedom, survives in prison only as a constitutional abstraction. When the court later declared my arrest illegal and ordered my release, I laughed—at the most farcical act of my life yet.

Well. I have been lucky to get bail—a near impossible thing in UAPA—though one keeps hearing the fond song: “Bail is the rule…”

I still miss my Big Data, my students, friends... who are too terrorised to keep contact with me. I can’t accept invitations for lectures beyond Maharashtra. Some six universities in Europe had invited me for their fellowships/lectures, but the courts disallowed. I dared to apply for permission for a litfest from among over a dozen invites, but it was rejected as ‘academic luxury’. I miss my usual life.

Well, bail is a little solace as I lost my life anyway! I still manage to laugh at myself… at this no laughing matter?

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

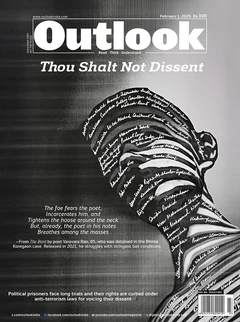

(This article is part of the Magazine issue titled Thou Shalt Not Dissent dated February 1, 2026, on political prisoners facing long trials and the curbing of their rights under anti-terrorism laws for voicing their dissent)

.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&format=webp&w=768&dpr=1.0)