The Cell and the Soul, Anand Teltumbde’s prison memoir, was unveiled by Dr. Bhalchandra Mungekar at an event attended by prominent lawyers and activists, transforming into a powerful reflection on justice and incarceration.

Senior advocate Mihir Desai criticised India’s unfulfilled prison reform promises, saying that despite multiple landmark judgments, “correctional institutions” remain brutal spaces devoid of accountability.

Dr Gayatri Singh described the memoir as “a mirror to the perversity of the system,” recounting how police illegally raided Teltumbde’s home and used media narratives to criminalise dissenting voices.

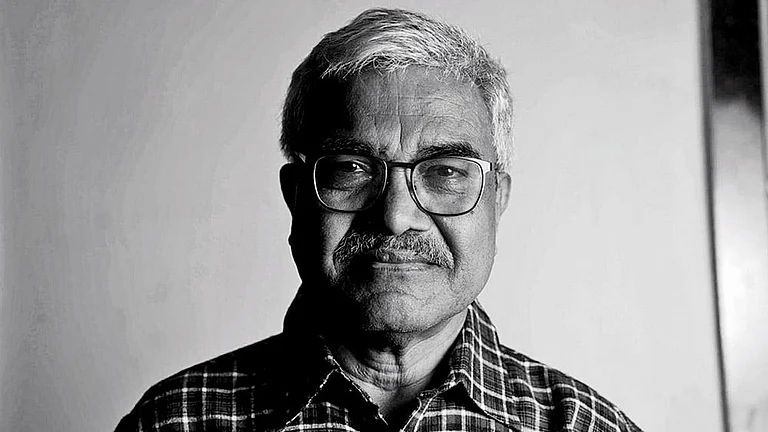

In a hall filled with quiet anticipation, Anand Teltumbde stood before an audience of writers, academics, and activists, not as a professor or public intellectual, but as a man who had lived through the confines of a prison cell. The noted scholar and civil rights activist, once accused in the Bhima Koregaon–Elgar Parishad case, unveiled his latest work, The Cell and the Soul, a memoir that peels back the layers of his 31 months inside Mumbai’s Taloja Central Jail.

The book is not merely an account of incarceration; it is a reflection on what it means to be free in a country where the boundaries between citizenship and suspicion often blur. Blending personal anguish with political observation, Teltumbde’s narrative traverses the stark realities of prison life, the monotony, the indignities, the small moments of resistance and situates them within a larger meditation on justice, identity, and dissent in contemporary India.

At the launch, co-organized by Bloomsbury Publishing and Innocence Network, Teltumbde’s words carried both disbelief and defiance. “I was under the illusion that this could never happen to me,” he said, his tone measured yet firm. “I thought these things were safeguards. But when the state decides to target you, none of it matters.”

His recollection of the police raid on his home marked the beginning of what would become both a physical and existential ordeal, one that The Cell and the Soul seeks to make sense of, not in bitterness, but in the language of reflection and resilience.

Teltumbde’s co-panellists, Ehtesham Siddiqui and Dr Abdul Wahid Shaikh, brought their own haunting echoes of prison life to the discussion, stories steeped in hunger, humiliation, and the grinding weight of bureaucratic cruelty. Their words transformed the literary launch into a moment of collective reckoning, where personal memories became political testimonies.

“There are no doctors, no medicines, not even mosquito nets without permission,” one of them said, his voice carrying the fatigue of years spent negotiating the simplest of human needs. “We tried to tell the truth about what we saw, and they called it anti-prison propaganda.” For Siddiqui, who spent 19 years in jail before finally being acquitted, writing became both survival and defiance.

“In Nagpur Central Jail, there was a noose hanging near my cell,” he recalled quietly. “Every time I saw it, I felt a shock. That’s when I decided to write.” He spoke, too, of the absence that haunts India’s prisons, not just of freedom, but of education. “I completed 22 courses in jail through IGNOU,” he said. “But getting enrolled was harder than studying.”

Their voices, measured, scarred, and deeply human, framed The Cell and the Soul not just as one man’s memoir, but as part of a larger chorus of those who have lived through the state’s silence.

Inside the Prison Walls

The evening saw the formal unveiling of The Cell and the Soul by Dr. Bhalchandra Mungekar, former Vice-Chancellor of Mumbai University and Congress Rajya Sabha MP, in the presence of senior advocates Mihir Desai and Dr. Gayatri Singh, both long associated with India’s civil liberties movement.

The gathering, sombre yet charged, felt less like a book launch and more like an intimate tribunal on justice and memory.

Mihir Desai, reflecting on decades of courtroom battles, spoke with quiet anger about the widening gulf between law and life inside India’s prisons. “Judges like to call jails ‘correctional institutions’, but the ground reality is anything but corrective,” he said. “From Hussainara Khatoon to Charles Sobhraj, there are hundreds of judgments on prison reform, none of which have been implemented. Two of the men on this stage were acquitted because there was no case. Yet not one police officer has been held accountable. Without accountability, injustice simply renews itself.”

Dr Gayatri Singh, equally incisive and emotional, called Teltumbde’s memoir “a mirror to the perversity of the system”. She recalled how police officers had illegally entered his home using a watchman’s keys, filmed private spaces, and then held a press conference to vilify him in public. “This book,” she said, “is not merely about a man behind bars, it’s about the violence of a state that seeks to criminalise thought”.

In The Cell and the Soul, Teltumbde recounts the stark realities of prison life, the systematic humiliation of new inmates, poor hygiene, and the loneliness of isolation. He writes about being placed in the high-security “Anda cell” meant to impress visitors but far removed from the conditions faced by ordinary prisoners. His memoir captures the fear, frustration, and resilience of those living under constant surveillance and control.

Of the COVID-19 lockdown, Teltumbde describes overcrowded quarantine zones, a lack of medical care, and underreporting of infections within Taloja jail, a reflection, he says, of how human dignity becomes expendable within the carceral system.

Teltumbde is among the 16 activists and academics arrested under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) in the Elgar Parishad–Bhima Koregaon case, which authorities have linked to alleged Maoist conspiracies. He continues to deny the charges, calling them “a clumsy and criminal fabrication” meant to stifle dissent.

In both his book and public remarks, Teltumbde reflects on how laws like the UAPA are weaponised to target voices critical of the state. “These cases are not about evidence but about narrative. They are meant to teach a lesson to those who think independently,” he said.