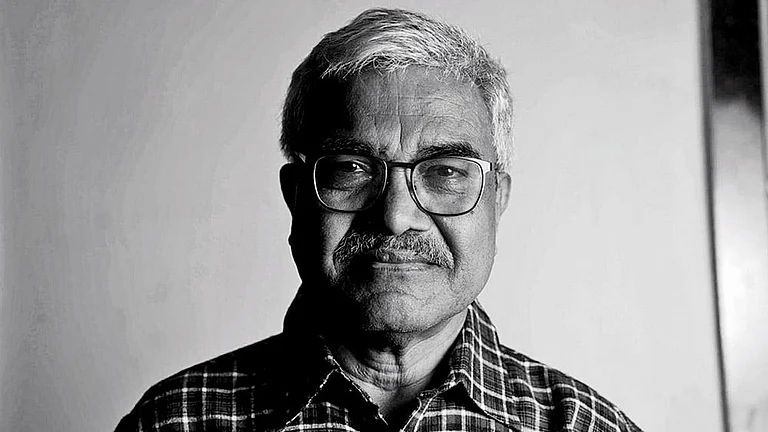

Anand Teltumbde’s The Cell and the Soul: A Prison Memoir presents before us a mirror in which we get to see our shattered democracy

The book begins with an important sentence—incarceration is often seen as a fate worse than death—and it is true for those who have not committed any unlawful activity.

Teltumbde, in the second chapter of the book, exposes the system that constantly denies people their basic human rights.

Democracy of a nation is defined by those who make it democratic. In the later part of the nation’s existence, the idea or ideal is given life by its leaders, bureaucrats, and people. One can easily identify a nation’s failing democracy by observing certain changes—restricted freedom, controlled choices, forced incarcerations and a climate of fear—which paralyse not only the development of the country, but also break the spine of its people, to ultimately disintegrate hope.

The democracy of India has always faced some hard and robust challenges, making it both strong and vulnerable. Yet, the challenges have been approachable. The intellectuals have always been heard and political parties have had to face strong dissent for suppressing voices.

In the last eleven years, the political climate, discourse, language and belief of India have become more extreme and intolerant. Fear has been normalised, incarceration is considered a solution, and the attitude of bullying is worn with pride. Today, there is a celebration when a learned and aware individual gets arrested or murdered. Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the plummeting of India’s Press Freedom Index is fearful and, at the same time, the rise in the number of identity-based imprisonments and deaths makes us ask an important question—are we really democratic? Many people avoid asking this question. Those who do are incarcerated.

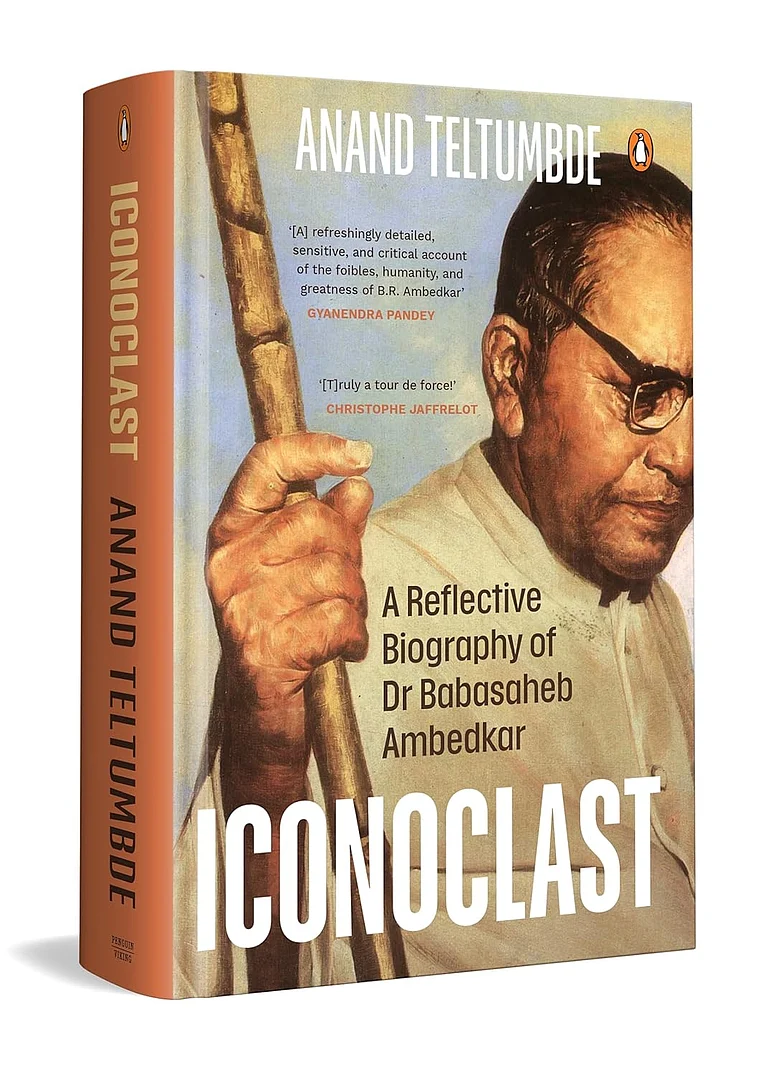

Anand Teltumbde’s The Cell and the Soul: A Prison Memoir presents before us a mirror in which we get to see our shattered democracy. From 2018 to 2019, the arrest of sixteen intellectuals with the help of fabricated documents, emails and voice recordings shook the liberty of this nation.

The intellectuals who got arrested were Sudha Bharadwaj, Rona Wilson, Shoma Sen, Varvara Rao, Father Stan Swamy, Anand Teltumbde, Gautam Navlakha, Sudhir Dhawale, Vernon Gonsalves and others, and through this particular memoir, Teltumbde hands us a magnifying lens so that we observe and experience what incarceration feels like, especially when the heart is hopeful towards the judiciary.

The book begins with an important sentence—incarceration is often seen as a fate worse than death—and it is true for those who have not committed any unlawful activity. The hope for freedom is crushed every day by the lawmakers of this nation, and while no one waits for death, Teltumbde focuses on how a prison forces an individual to ponder about it since its darkness leaves very little space to make us believe in something else. It haunts the mind with morbidity and lack of kindness.

In the first chapter, Teltumbde focuses on stripping the significant lies that have been filed against him by the high-ranking police officials to curb dissent in the name of law and order. He mentions how the Additional Director General of Police (ADGP), Param Bir Singh, read out a letter that was fabricated using a seminar’s topic, which was available in the public domain.

Teltumbde writes that even after everything, he chose to put his faith in the judiciary and the media, which he hoped would understand the motive behind the fabrication. Unfortunately, a broken democracy targets hope since it is the only source of belief, dissent and survival. The paid media channels used their medium to malign his image and unsurprisingly, people believed their words. The letters, which were supposed to be handled by the police, reached news channels, and this activity was not questioned. Even though the judiciary warned the police about this unlawful act, the oppression of Teltumbde and other intellectuals persisted because the government wanted to crush those who wanted to unveil the truth.

We have been told from our childhood that it is not good to make either a friend or a foe out of a police officer. The system has deliberately induced fear in the minds of our parents by quoting the fear that police officials are handed to vanquish anyone whom the authority cannot stand. Only in fiction, like films and books, do we get to listen to their responsibilities and how they need to follow the Constitution.

Teltumbde, in the second chapter of the book, exposes the system that constantly denies people their basic human rights. In one instance, when he wanted to file an official complaint against Singh for distributing discreet evidence to the national media channels, the Principal Secretary refused to give him permission to do so. He highlights that even after multiple accusations against the ADGP, he had the last laugh after the BJP came into power in Maharashtra. It dismissed all the charges against him, revoked his suspension, and called the accusations a failure of the former government.

Incarcerating people who dissent is the authority’s method to show that even with facts, truth and education, the former has to be afraid of the latter. From the outside, most of us have a little idea of what a prison looks like and how people change in its presence. Therefore, we glorify the activity of getting arrested during a protest, because amidst absolute hopelessness, this glorification projects a glimmer of hope and faith.

Teltumbde does not refrain from giving us an actual idea of life inside a prison cell. He addresses how his younger self had a contradictory image of prison and prisoners. As a child, he used to question the fate of prisoners, since most of them wanted freedom and development for their countries. But when he encountered a prison for the first time, it rattled his belief. He dug deep to understand even the criminals and why they committed the crimes they were accused of. All his questions were directed towards the system, which cultivated a climate of inequality, injustice and bitterness, which led to the germination of criminals. But he writes that he never thought that one day, he will be there in a dark prison, with no bed but only a cheap cot to rest his back.

A civilisation that grew up by keeping gurus above everyone, has, today, normalised the harassment of professors and intellectuals. It solidifies the idea that we have butchered our own conscience and forgotten the ideals of this nation, only to take pride in being unjust.

In the BK-16 case, the incarceration took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, which further weakened the protest against these unconstitutional arrests. The accusations against the Muslims, the Tablighi Jamaat and migrant workers acted as a good cover-up for the general citizens to remain unaware of any of these false evidences, followed by arrests on a mass scale. The hatred against the Muslim community reached its maximum during the pandemic, but Teltumbde puts forth an argument where he asks why the government turned a blind eye to the Kumbh mela in Haridwar, which, according to the reports of the World Health Organization (WHO) and The Lancet, was the major reason for the spread of the virus.

The effect of the pandemic did not leave the prisoners alone, and even amidst thousands of prisoners, social distancing was applied. The prisoners were denied proper diet, hygienic bathrooms and basic resources. Teltumbde argues that the death of Father Stan Swamy was a custodial death. He had Parkinson’s disease and to drink juice, he needed a straw, which the prison officials did not provide. His kindness suddenly had to meet the demons that human beings are capable of becoming. Even with the lack of resources, he worried for the workers in the jail and used to speak about how they should be given adequate food during the pandemic.

Teltumbde, in the chapter Entering the Hellhole, describes the prison as something that shreds the right to dignity enshrined in Article 21 of the Constitution. It is the fundamental and constitutional duty of prison officials to provide pen, paper and books to a political prisoner. Teltumbde requested the Superintendent of Police (SP) for a pen and a blank sheet of paper to keep his notes, but the official declined the request. Even in the presence of a biometric database linked with the Aadhaar, Teltumbde was asked to provide his fingerprints on several papers to make his spine weaker with the constant and continuous harassment. Later, when he was transferred to Taloja jail, he was stripped naked and searched in the presence of CCTV cameras. Humiliation is instrumental for fascists to make their power known not only to the prisoners but also to their loved ones.

Prisons are also not free of discrimination—a cell with more chaos is entertainment for the authority—and like the outside world, Teltumbde’s identity was also seen with raised eyebrows. But, at the same time, a few upper caste prisoners and constables demonstrated humane acts, which makes the cell not only a hellhole, but also a tiny community that’s treated like an inferno.

The prime targets of authority (whom they consider their nemesis) are not just forced into prisons. They are barred from expressing their views, implementing their fundamental rights and, most importantly, making their identity known. Teltumbde writes that the intellectuals arrested in the BK-16 case were barred from writing letters to the courts, and if permitted to write, the process of depositing them was deliberately delayed by police officials. Later, several verdicts came in favour of the intellectuals and criticised the inability of the police, but the primary question here is: do the verdicts stand strong and have any impact if they come after months of suffering?

Teltumbde attaches an article he wrote in the latter part of his prison life, where he criticises the Narendra Modi government’s conversion of Public Sector Units (PSUs) into private sectors, promising that it would boost the economy. The article’s prime concern is the separation of the country’s economy from the Constitutional vision. The Caravan published the article. Later, the SP summoned Teltumbde for writing the piece and even though the latter said that publishing an article from prison is not unlawful, the former banned Teltumbde and all his co-accused from receiving or sending any letter. The move shows how prisons work against the Constitution and break people on a daily basis.

In the book, Teltumbde strongly criticises the existence of prisons by comparing Indian cells with those of other developed countries, like Norway, Portugal, New Zealand, and Switzerland. In these small yet efficient countries, the operation of correction centres or prisons is constantly updated so that they refrain from hurting a prisoner’s conscience.

Yet, he has very little hope of reformation of Indian prisons since the reality is far worse than in many other countries. He wants prisons to be abolished so that the correction of a person’s activities becomes possible. Teltumbde’s The Cell and the Soul offers us a significant insight into not only prisons, but also those who run them and how they contribute to the deterioration of judicial processing, availability of basic resources and hygiene.

In addition, Teltumbde criticises the government and its systemic attack on India’s Constitution. His first-hand experience of injustice by the system makes this memoir important to understand the complexity of the judiciary and how the government keeps neglecting these complexities to attain its objective. The book addresses what is wrong with the nation in the present time.

This story appeared as Another Brick In The Wall in Out of Syllabus, Outlook’s November 1 issue, which explored how the spirit of questioning, debate, and dissent—the lifeblood of true education—is being stifled in universities across the country, where conformity is prized over curiosity, protests are curtailed, and critical thinking is replaced by rote learning, raising urgent questions about the future of student agency, intellectual freedom, and democratic engagement.