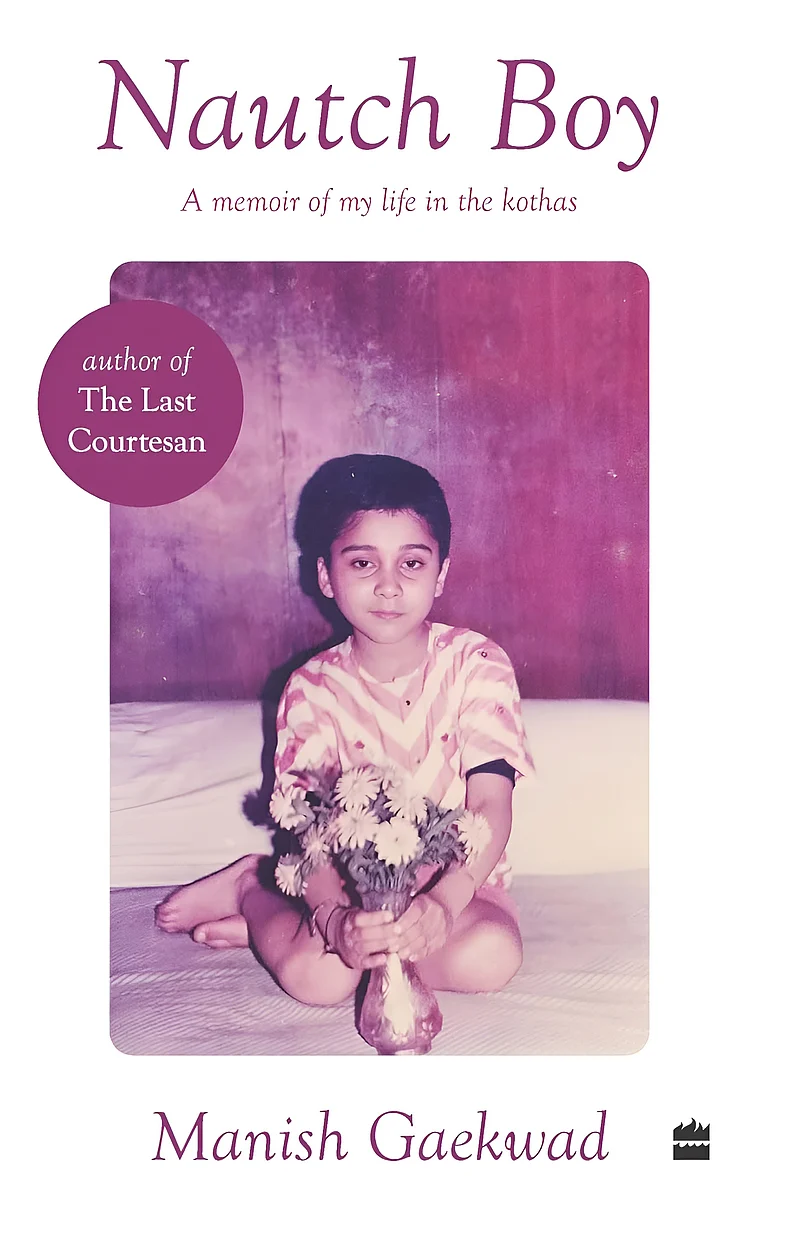

Nautch Boy explores Manish Gaekwad’s life growing up in Kolkata and Mumbai’s kothas.

The memoir examines sex work, identity, consent, and the art of courtesans.

Through his mother’s story, Gaekwad reflects on stigma, resilience, and self-discovery.

There are very few works of art which can identify sex work from a personal perspective by both accepting and nullifying the idea of victimhood. It is the reality of India that whenever a kotha (brothel) comes up in a conversation, society approaches the subject through a binary.

The profession is either considered something derogatory or the people who speak about it become the flagbearers of liberation, who believe that after years of conditioning, their profession is a stain on their identity. Neither of these are entirely true and a bifocal lens would not be of much help when sex work is the motif.

Manish Gaekwad’s memoir Nautch Boy: A Memoir of My Life in the Kothas, takes us back into the lives of tawaifs. Unlike his last book, The Last Courtesan: Writing My Mother’s Memoir, here he gives us a glimpse of the lives of women who take their physical presence to be a work of art. This memoir delves into consent, the dynamics of freedom, and the ways in which these women manage to live their lives by ignoring the ‘moral gaze’.

Reality vs. Fantasy

In Kamal Amrohi’s film Pakeezah (1972), we get to see a helpless and gloomy courtesan (Meena Kumari) wearing the disguise of grace only to dance before men and woo them. Although the director focuses on the choreography and the atmosphere of glamour that surrounds the courtesan, in the story, he brings in the passivity and vulnerability of the courtesan. He perfected the stereotype that society likes to attach to a courtesan (and most women, in fact).

In the introduction of his memoir, Gaekwad gives us a vivid description of how his mother, a courtesan, stuck to her choices, and even in vulnerable situations in the kotha, she decided her own fate. This is the first contradiction that we find between what is shown in mainstream cinema and reality. The writer’s mother in this book sets off a ripple effect, which spreads, inspiring the idea of independence. In a kotha, women live as a community and they are barred from the rest of society. So, even a slight glimmer of hope can work as a powerful catalyst.

The Core of a Storm

Decades before Srijit Mukherji’s film Rajkahini addressed the power of sex workers, Shyam Benegal approached their lives through his film Mandi, where a major figure named Rukmini Bai, played by Shabana Azmi, stood for the rights of sex workers. Mainstream cinema of the time rarely focused on the inner worlds of sex workers.

In the first two chapters of his memoir, Gaekwad traces the trajectory of his mother’s journey into the kothas of Kolkata and Mumbai. He also presents the two cities from the position of those who know the cities and its citizens best, but are ignored by society. Vulnerability breaks like a bangle for the courtesans, and what remains is a vacant heart which can hold the calm and the storm. The writer carries both of these in the pages of his memoir.

Where Art Always Finds a Home

Muzaffar Ali’s cinematic masterpiece, Umrao Jaan, places the art of the tawaifs in the forefront, and after a while, the character becomes a dancer/singer for the audience more than a tawaif. Similarly, Gaekwad approaches his mother’s art form to not only place before us the art that she demonstrates on a daily basis, but also as a means to discover his own sexual orientation.

From learning Ghalib’s couplets to working on certain body movements with a tinge of Kathak, through his mother, he presents a community whose members may not be established artists, but have been constant contributors to art. The writer finds his orientation in the beats of his mother’s ghungroo. His friends admonish him when he tries to mimic his mother’s body language. An art form that is restricted to women flows to Manish, but no patriarchal society would cherish the concept of a man identifying with the woman that lives in him. Gaekwad stuck to his understanding of his Self, and this led him to be identified as a nautch boy, and several other identities that were considered derogatory. Here, he gave birth to a protest.

The Chaos of Growing Up Around Sex

Gaekwad does not refrain from highlighting the sexual activities around him. His experience of growing up around patrons who have their own fetishes to fulfil but have no room for love is terrible. This also drove him to pursue something different, which gives him enough freedom to tell stories. For a sex worker, the absence of pleasure is an evident reality. Yet they accept the patrons’ demands because it is their profession.

In a patriarchal system, even when the choice lies in the hands of the courtesans, pleasure resides with the men only. To grow up in the midst of this can be a curse, but Gaekwad points out the fact that he understood a woman’s body, her needs and the worth of art in the kotha he grew up in. It was a home of many rooms. And he lived in all of them.

Gaekwad explored many professions to find his own self, and during this journey, he was reminded by many of his identity, his fatherless existence, and his childhood in a socially ‘immoral’ place. Standing up to bullies, oppressive teachers and narcissistic bosses was not an easy journey for him. Yet, there was a sense of liberation; a certain joy that he experienced when he saw his mother performing on stage for her patrons; a sense of satisfaction that the steps used to flow to her easily. People who have not lived under such conditions would not be able to fathom that even in a kotha, life has meaning.

Nautch Boy: A Memoir of My Life in the Kothas is an essential book because it shows us how a human being gets to know his own self, even when the outer world is ready to corrode his confidence. It is also important because through the writer, we find insights into the lives of those who we know more as sex workers and less as human beings. The book is witty in parts, philosophical, and emotional throughout. It goes beyond lust and pleasure to introduce us to the small, but necessary elements of life. Its non-preachy voice leaves us with an open mind and a fulfilled heart.

(views expressed are personal)

Kabir Deb is a poet and Interview Editor of Usawa Literary Review.