Summary of this article

The essay situates Kunjana Parashar within the evolving cultural lineage of the “Bombay Poet,” tracing continuities from Kolatkar to today.

They Gather Around Me, the Animals forges a new poetic idiom rooted in ecological intimacy, cosmopolitan locality and speculative language.

Parashar’s work blends mentorship, activism and craft, making poetry both a community practice and a politically resonant art form.

Milieu: The “Bombay Poet” as a Cultural Phenomenon

The last decade has seen the “Bombay” Cultural Scene turn electric with nostalgic energy. This gaze is directed at the poets who crafted a fresh path through language and place (city), from the sātthotari (1960s) up until the turn of the century. The recent exhibitions (at the Guild) exploring Adil Jussawalla’s personal archives, are testament to this creative excitement – this living past of “urban” poetry. The much-coveted tag of “Bombay Poet” is perhaps more appropriate when speaking of individual poets, rather than a “movement”. Literary critics Anjali Nerlekar (“Bombay Modern”) and Laetitia Zecchini have written extensively about the “cosmopolitan” air that buffeted a changing idiom of Indian writing in English during this period – Arun Kolatkar’s 2004 collection Kala Ghoda Poems helps fortify Nerlekar’s argument about an urban placemaking whose contours extend beyond its geography and timezones (Zecchini appropriately describes this as the “cosmopolitan local”).

Alongside a discursive resurrection of poets such as Nissim Ezekiel and Dom Moraes (pre sātthotari), we see a revival of the critical assessment of scholars, such as A.K. Ramanujan (whose work in poetry, and translation, is well known) and Bruce King. King’s authoritative critical praise (posthumously) adorns Arundhati Subramaniam’s fabulous latest collection of poems – The Gallery of Upside Down Women – alongside blurbs by Keki Daruwalla and K. Satchitanandan (among others). Multiple publishing houses – independent and mainstream, poets, and contemporary writers – are publishing and curating Adil Jussawalla’s writings. This is excellent news – and we must be grateful to this bounty of literature! These critical publications, in many ways, bookend the avante-garde creative fervour of his compatriots and contemporaries including Arun Kolatkar, A.K.

Mehrotra, Gieve Patel, Eunice De Souza, Kersey Katrak, Saleem Peeradina and others. This is not an exhaustive list, of course; the contributions of all the writers, critics, artists, publishers, even patrons who were active at the time, are perhaps better sought out by speaking to the poets who were writing, or starting out, at that time. Saranya Subramanian’s The Bombay Poetry Crawl – a research initiative that platforms young poets, artists and scholars, has become quite popular, in this pursuit. It is in this complex milieu of intergenerational creative collaboration and production that I seek to read Kunjana Parashar’s spectacular debut collection of poetry-They Gather Around Me, the Animals.

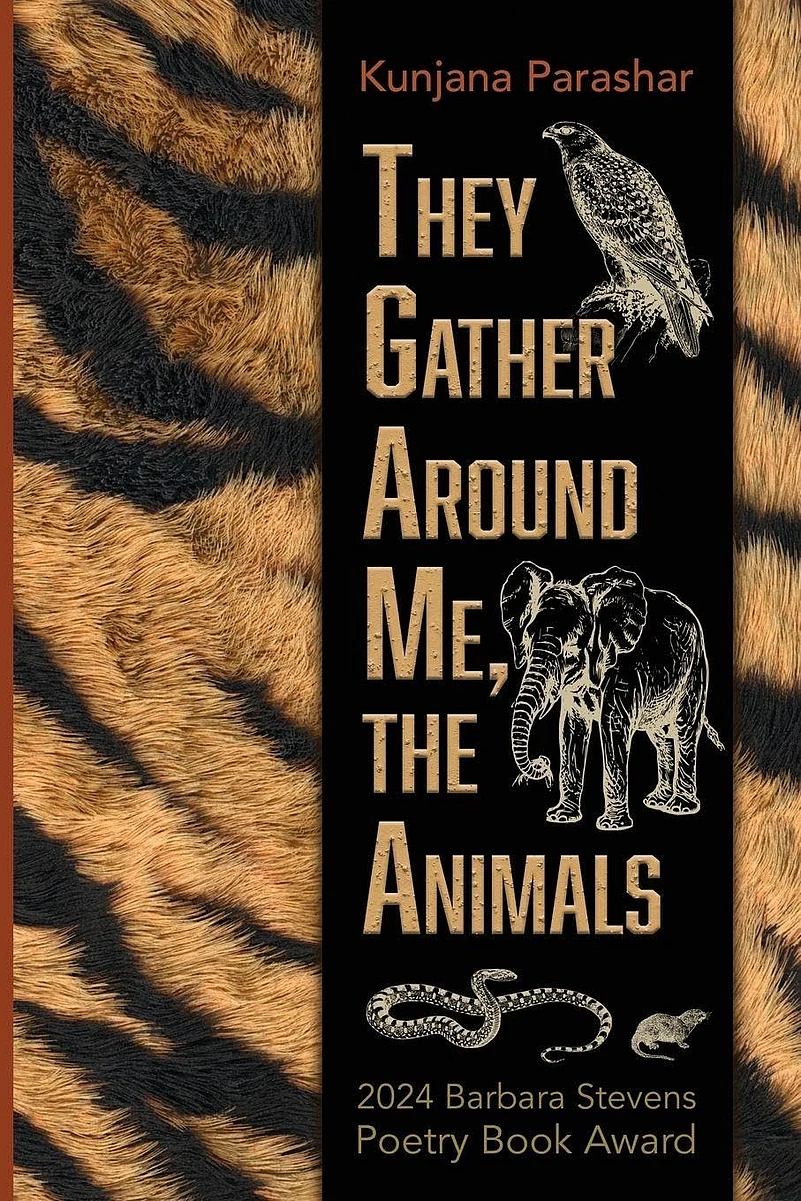

Poetic Comradeship

Parashar is a young poet, based in Mumbai – a subject that frequently sidles into the landscape of her “ecological” musings about the contemporary world. Her poetic practice, and attitude towards both the form, and its exponents, is an epitome of the curatorial intentionality of “small kindnesses” (with apologies to Danusha Laméris). In a very short time, she has garnered several accolades in the poetry world - her bio in The Adroit Journal reads: “Her manuscript They Gather Around Me, the Animals, selected by Diane Seuss, has won the 2024 Barbara Stevens Poetry Book Award. She has received the Toto Funds the Arts award and the Deepankar Khiwani Memorial Prize. She is an associate editor at The Bombay Literary Magazine.”

In a local publication environment that is suspicious of poetry (because of its low “market” value) They Gather Around Me, the Animals jumps the queue, having been endorsed by a well-known ‘international’ poet. Many seek out her social media pages for advice, guidance, and gentle, empathetic feedback. In the last decade, young practitioners of poetry in this country have been complaining about the lack of a “community” of other writers, the absence of feedback mechanisms, and effective mentorship. This has led to a number of poetry collectives emerging online, with an emphasis on workshops. Parashar’s regular engagement with a burgeoning audience of committed and critical creative writers and readers includes important information about international poetry journals, places to submit, ways to edit, and structure poetry manuscripts (among other things).

These are precious learnings gained from experience. Graduate students (and their parents) willingly shell out large sums of money to foreign universities to avail of this “elite”, protected knowledge via the “MFA circuit”. This is one of the reasons she has become something of a celebrity in online poetry circles, and also, why her book of poetry is reaching such a large reading public, despite costing a small fortune online (since it is an international publisher). Parashar has made her book accessible (and affordable) to readers in India, by purchasing author copies, and selling them to readers from all parts of the country at a highly discounted rate. One might call this a kind of endearing ‘literary activism’, but perhaps, Parashar’s animal heart might shy away from that label.

“The Total Animal Soup of Time”

I am not sure what Allen Ginsberg would make of Parashar’s poems, but as I carefully unraveled the world she inhabited with her words, his spirited description (in Howl) of the vortex in which he found his friend, Carl Solomon, came ringing back to me. Parashar’s “animals” (and ghosts of animals) gather around the reader, in a chaotic exuberance that liberates, even as it cautions. I thought of Shylock’s spontaneous anguish in The Merchant of Venice, too, rendered metaphorically with the evocative turn of phrase ‘a wilderness of monkeys'. Days after I put down her book, I am still reeling from the tremor of her words in phrases such as ‘black chorus of clouds’, ‘litany of feathers’, and ‘the green bone of things’. My favourite among these periphrastic genitives is the ‘Kopar of Ghats’ - one of the many examples that mark Parashar’s voice as critical in a new generation of young writers invoking their own complex “cosmopolitan local”.

But Parashar’s poetry extends far beyond the scope of Mumbai or even “Bombay” city. While reading her writing, I felt that her poetry neatly reworked the labels of “argument” and “description” into a new idiom of poetic expression that pulls the reader into its alternating epic and microscopic scope. Her metaphors and imagery take us far away from cliché, and in their evocative precision, they come to us like urgent missives – sometimes as an SOS, and sometimes a sudden, spontaneous ode of unbidden joy for all things beautiful and messy. Her vision is more-than-human (“non-human” feels like a feeble reduction), deepening the anthropocentric gaze, even as it embraces sensitivity while engaging with the creatures and life-forms that make up our lived environment. In a poem where she writes about “forgetting” and about trying to “memorise” what was “going, what would be gone” her final plea echoes strangely with the political heft of Aamir Aziz’s “Sab Yaad Rakha Jaega”. But hers is a cry for help, a reckless warning: “Someone must remember…Someone must write it down”.

I believe that it is this quality in Parashar’s poetry that makes it timeless, yet compellingly prescient. Even as she marvels at its granular beauty, Parashar laments a world that has been assaulted by the human virus. She does this, without ever employing a pedantic tone. As she draws attention to what we are doing to the skies and the earth, the forests and the rivers, how we’re polluting and destroying, she gestures towards that which we have already lost, but also what we are in the danger of losing. She does this with an intuitive persona that uses empathy to enter into the inhabited world of “things”, objects, and places - living beings. This is a subtle ecological politics, that is no less strident than the rhetorics of “identity politics”. A transformational intimacy with observed and experienced phenomena makes the work truly personal and universally political. “Who am I to ruin the unity of things for the sake of a sanitary impulse…?” she asks in a poem entitled On Not Cleaning the Bathroom; and I was left marvelling at the dexterity with which she weaves ordinary objects into a landscape of extraordinary world-changing questions.

A New Language of R-Urban Ecology

Parashar’s words are already being used in college syllabi – for instance, her poems are being taught (in an elective called Introduction to Critical Environmental Studies) in NLSIU Bengaluru, and IIT, Madras. Some years ago, Kunjana and I were discussing the idea of poets who “sacrificed craft at the altar of truth”. We were discussing the use (in a poem) of a particular colour while describing a “victim’s” shirt, or the texture of his “oppressor’s” moustache. Does it matter what the actual colour or texture was? Isn’t it more important that the “rendered” colour, or the crafted emotional plot makes the reader feel the poet, rather than putting the burden of truth and testimony on the poem?

This discussion has stayed with me over all these years and the idea has opened up my ken to the speculative possibilities of language, and narrative. In my mind, Kunjana Parashar’s language does to contemporary Indian Poetry what Ursula K. Le Guin’s narrative “anthropological” aesthetics does to fiction - it brings in the discursive register of the “speculative”. I was cross with the poet for making me looking up words such as “pipistrelles” and “zoanthids”, “aphotic” and “gular”. But the looking up made me smile – I realised that this was more than poetry, it was an education.

In the last analysis, Parashar’s poems recruit time (the past, the present and the future) and mythology, local experiences and “events” of global import, to unravel what is personal, political and inter-planetary in this thing we call life. I found it very difficult to find a “favourite” poem – I had my task cut out, sifting through titles such as Frogs of Bhiwandi, Poem with No Birdsong in It, Dewing, and Ode to a toxic marsh. The poem What are you, an environmentalist?/ or a love letter to mumbai’s/ intertidal zone perhaps has the line that is most memorable to someone who identifies as a "Bambaiyya” – “i love you, my sweet bombil.”

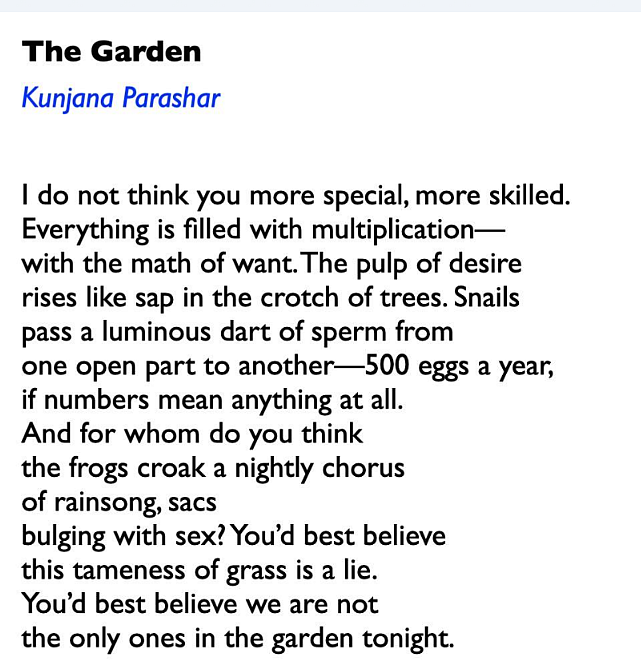

But I decided finally, to share the poem that spoke to me, with the syntax of desire, on the very first reading. Its sheen refuses to go away, even after multiple revisits.

For Indian readers, Kunjana Parashar's debut collection of poetry, (published by NFPS Press), "They Gather Around Me, The Animals", can be found on Amazon.

Aranya is a poet, currently based in Delhi, a place to which he doesn't belong.